Learning to Do Historical Research

A Primer for Environmental Historians and Others

William Cronon

Introduction

William Cronon

(Photo by Rees Candee)

Welcome! We've designed this website as a basic introduction to historical research for anyone and everyone who is interested in exploring the past.

Whenever you frame a question with reference to how things have changed over time, you commit yourself to doing historical research. All of us do this all the time, but not everyone thinks very carefully about the best ways of finding information about the past and how it relates to the present.

The website is divided into two major sections:

- The first surveys essential stages of the research process.

- The second surveys different kinds of documents that can offer invaluable information and insights about the past.

Individual pages are designed to be read from beginning to end, and the pages about the research process follow a logical order that mimics the phases of working on a historical project. But individual pages (especially the ones about sources) can also be read in any order.

Although we've constructed this site especially for environmental historians, and have generally provided environmental examples, we've tried to make it as helpful as possible for anyone seeking to learn the craft of doing historical research.

Almost any question you can imagine asking about any topic will become more intriguing if you consider the ways in which the subject you're investigating has changed over time.

- Interested in how much milk, cheese, and butter Wisconsin dairy farmers produced last year? If so, you might want to know how that compares with ten years ago...or a century ago.

- Are you curious about the risks posed by new antibiotic-resistant forms of tuberculosis that have been becoming more prevalent in recent years? Then you might want to know how common the disease was before antibiotics became widely available.

- Would you like to know the possible impacts on modern economies of changing oil prices? Then you might want to study how such economies responded to past changes in energy prices—and how people used to work and move around before gasoline and other petroleum products were such a big part of their lives.

The list of questions like these is literally infinite.

Historical research can be an amazing adventure once you've experienced how fascinating it can be.

We hope this website will encourage you to give it a try!

(Please feel free to link to this site and share the URL with others who might find it useful. Teachers are more than welcome to use the site in their classes if they're so inclined.)

Mastering the Stages of the Research Process

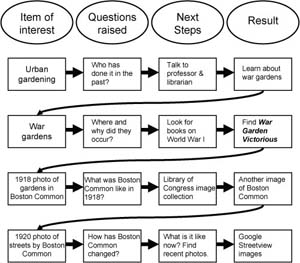

There are certain predictable stages that all historical research questions go through:

As you can see, these form a logical sequence, but it's important to stress that these "stages" are in fact deeply entangled with each other, so that doing this kind of research is always an iterative process. You won't be able to ask good questions if you can't learn to think of them relative to documents—and each new document you find is likely to generate new questions that you never could have anticipated at the beginning of your research. That's half the fun.

Still, it sometimes helps to think about these stages as if they were discrete from each other, so we've designed a page for each of them.

Return to Top of Page

Asking Questions is an Iterative Process

It's harder than it looks to ask good research questions. Often the question with which we start is too vague or unfocused to offer much help for how we should go about answering it. Especially when the question we want to answer relates to the past, it must point toward documents with which it can be answered.

Asking "How did Americans respond to flu epidemics in the past?" is so broad that it's hard to know how even to get started with it. Asking instead "How did daily newspapers in the United States cover the world-wide flu epidemic of 1918 that killed more human beings than all the soldiers who died in World War I?" is far more focused, and includes a crucial group of documents right in the body of the question.

To learn more about the craft of asking good research questions, click here.

Return to Top of Page

UW-Madison Memorial Library Card Catalog

Paradoxical though it may sound, one of the most challenging things about doing historical research is that the past doesn't exist anymore.

Unlike science, where one can set up a laboratory experiment or perform field investigations that describe the world as it exists right now, the past survives only as fragments that remain from a time that is no more. Studying history means collecting these fragments and figuring out what they mean.

Historians use the word "documents" to describe these surviving remnants of the past. A document can be a book or a newspaper, but it can also be almost anything else that contains traces of the past: a photograph, a map, an artifact, a memory, a landscape—almost anything.

No matter what question you want to ask about the past, your second question should always be "What are the documents?"

Learn more about how to do this by clicking here.

Return to Top of Page

Don't ever hesitate to ask for help from a librarian

We've all gotten used to relying on Google when we're searching for information. We enter a few keywords or a question in the Google search box, and if we're lucky, up pops a ranked list of websites that tell us what we want to know.

Google and other search engines are the most powerful tools for finding information that humanity has ever created. They're amazing. Unfortunately, most of us don't use them nearly as skillfully we should. Indeed, people's ability to perform searches has been declining as search engines have grown in power.

More importantly, many historical documents aren't on the public Web that Google indexes—indeed, most aren't yet on the Web at all. To find them, you'll need to become skilled in more traditional tools for navigating libraries. The reward for doing so is that you'll then be able to discover historical treasures that are hiding in plain view if only you know where to look for them.

This task may seem daunting at first, but don't be discouraged. This part of historical research is like being a detective, and can be enormous fun, To learn more about how to do it, click here.

Return to Top of Page

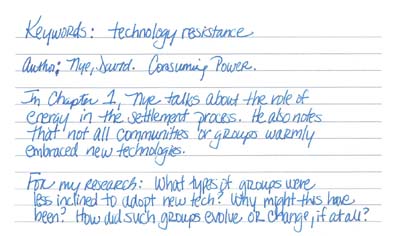

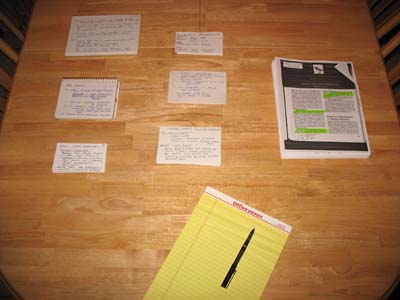

Note-taking keywords

Once you become seriously involved in gathering historical documents, they'll quickly become far more numerous than you ever would have imagined when you began your project. Unless you come up with effective ways of taking notes and organizing what you find as you search, you'll never be able to find things again when the time comes to write up your argument or tell your story.

We all have different ways of taking notes and organizing our files, but there are some tried-and-true principles that all good researchers follow when keeping track of the information they find.

You will save yourself enormous amounts of time (and grief!) if you apply these principles in your own work.

To learn more about note-taking and organizing your documents, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Organizing Your Notes Is Crucial to Successful Writing

The goal of historical research isn't just to gather documents and collect information. These are the raw materials of history, not history itself.

No, your real goal is to build an argument and tell a story. What happened back then, and why? What were the consequences, and why should we care about them?

The sooner in your research process you can start grappling with these deeper issues of argument and narrative, the more you'll learn and the subtler your understanding of your question will become.

Sketching arguments, trying out stories, and building outlines that will provide the skeleton of what you'll eventually write: there are few more vital skills for doing historical research.

To learn more about this challenging process, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Uncommon Ground Cover

You are not the first person ever to be interested in the subject you're researching. Far from it. You are simply the latest in a long chain of people who have shared your curiosity and passion for the subject you're investigating.

You can enhance your own thinking immeasurably by learning how other people have answered the questions that intrigue you. To do this, you need to build a geneaology—a family tree—of earlier works that relate to your own.

Historians sometimes use the phrase "primary sources" to refer to the original documents that provide the building blocks for everything we know about the past. They use the phrase "secondary sources" to refer to the writings of scholars and other people who have used primary documents to interpret the past.

Identifying the most important secondary sources for your topic is a key part of your research. Once you've done so, you'll want to figure out how your own ideas and arguments relate to what the authors of those secondary sources have said about your topic.

Doing this is called "positioning your argument," a skill that can dramatically enhance the significance of what you yourself write. To learn more about this, click here.

Return to Top of Page

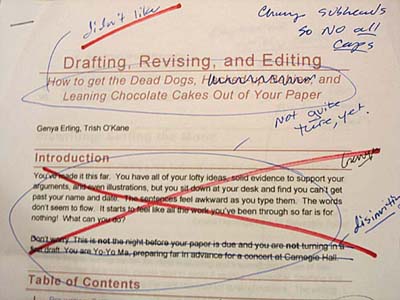

Marked-Up Draft of Our Own Web Page

All good writing is rewriting. Don't ever forget this.

One of the biggest mistakes students make when writing a paper is leaving themselves so little time before the assignment is due that they never have the chance to rewrite. Starting early enough that you can produce one or more rough drafts enables you not only to enhance the quality of your prose, but the depth of your ideas as well.

We rarely really know what we think about a subject until we try to write about it. This means that drafting and revising are deeper parts of the research process than we typically recognize. By starting to write while you're still in the process of gathering documents, you will very likely find yourself discovering that you need additional documents that you hadn't recognized would be so important until you actually began to sketch your argument and tell your story.

By starting early, you also give yourself permission to write a rougher draft than would have been possible if you were up against a deadline for turning in your assignment—and that can diminish the stress and anxiety we all feel when we write.

To learn how you can become a better writer, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Sources for Environmental History: Finding Your Way Back to the Past

We can't find out anything about the past without documents—the fragments that have survived from that past world that no longer exists. To do historical research, you need to learn to think through documents, framing questions that point toward the records that will enable you to answer those questions.

Although there are many, many kinds of documents, some are so important that anyone doing historical research should be aware of their existence, know how to find them, and learn how to interpret them. Among the most useful especially for environmental history are:

We've produced an extended web page for each of these types of documents, and offer a brief catalog of these web pages below.

Return to Top of Page

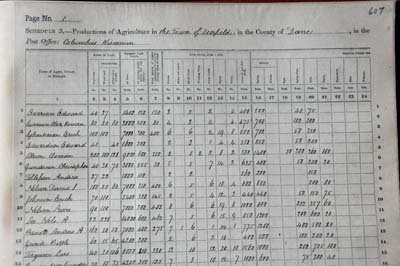

Manuscript Census of Agriculture

Much of what you'll research exists in printed books that you'll find in libraries, or on websites that you'll find by using search engines like Google. You'll want to become expert in finding these.

But some of the most magical historical documents have never been printed at all. They exist as letters or diaries or other unique items that are held in collections called archives. There's something very powerful about handling a piece of paper signed by Abraham Lincoln, the draft of a poem by Robert Frost, a daily journal kept by a migrant on the trail to the California Gold Rush—or even letters between your grandparents that have been sitting unread in a family attic for decades.

Historians call these unique unprinted documents manuscripts. Learning how to find them is among the most challenging and intriguing of historical skills, since by their very nature they come in all shapes and sizes, and can be organized in many ways.

You'll want help from an archivist when beginning to explore a manuscript collection, but to get a better sense of what it feels like to do this, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Reading Newspapers on Microfilm

If you want to get a slice of life about what's been happening in the world recently, one of the best places you can turn is a daily newspaper or a weekly newsmagazine—or, these days, maybe the website for these publications.

The same is true if you want to explore the past.

Because newspapers and magazines often seek to provide readers with summaries of the latest news and fashions, and what people are thinking about such matters, they can be immensely helpful in helping you understand what life was like at a particular moment in the past.

If you don't believe us, go to a library and pick out any two newspapers at random (from your hometown if possible) for two dates separated by at least fifty years. Look at all the pages—the headlines, the editorials, the sports pages, the business news, the advertisements—and ask how much the world had changed in the years between those two documents. There's almost no end to the questions you can ask about the changes you'll see in just two randomly chosen newspapers.

But precisely because periodicals like these are such an astonishingly rich source, it can be really confusing trying to find information in them. If you don't know what you're doing, it can feel like you're looking for a needle in a haystack.

Here too there are lots of helpful techniques for using these kinds of documents—techniques that will prove deeply rewarding if you apply them to your own research.

We offer an overview of the endless fascinations of periodical sources here.

Return to Top of Page

Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics

There is almost no aspect of human life that isn't affected in one way or another by the activities of governments, whether at the local, state, national, or international levels.

Because governments by their nature do a better job than most organizations of keeping track of what they do—whether writing laws or prosecuting criminals or collecting taxes or fighting wars or regulating economies or managing natural resources—they are prolific producers of documents. Government document collections are among the largest and richest in the world. No matter what the topic that interests you, there will be numerous government documents that relate to it.

The problem is finding those documents. Each government has its own unique way of organizing its records, and archivists spend entire lifetimes learning to navigate these records.

Most of us have no idea just how rich a government document collection or a law library can be in helping us understand things in the world we care about. If you can get even a brief taste of the power of these specialized sources, you'll be more inclined to think of them in the future whenever you're contemplating research projects you might wish to undertake.

So...take the time to sample government documents. For some suggestions about how to do so, click here

Return to Top of Page

Earthrise, Apollo 8

Some documents are so obscure or complicated that we hardly know what to do with them when we first encounter them.

Not photographs or other images. Because we've all grown up in an image-saturated age, we all have much-practiced skills for interpreting and understanding what we see in a photograph. If the image is historical, and depicts a place we already know, we find ourselves almost automatically comparing what we see (and don't see) in the image with what we remember from our own knowledge of the place.

Let's be honest. Viewing historical photographs is just plain fun. Few other documents are so instantly accessible and engaging, so if you can find photographic documents relevant to the topic you're researching, that topic will almost certainly become more interesting to you, with a host of new questions generated by the simple act of gazing at an image.

But be careful. Like all documents, photographs require critical reading to be properly interpreted and understood...and finding them can be yet another detective hunt.

We introduce you to this wonderful genre of documents here.

Return to Top of Page

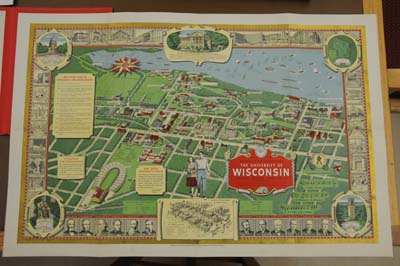

Centennial Map of University of Wisconsin Campus, 1948

If you know how to read them, historical maps are like photographs in being among the most engaging and powerful of historical documents. Because they are designed to depict places in simplified or thematic ways, they are especially powerful tools for doing environmental history.

Like many of the documents we discuss on this website, maps are often collected in specialized libraries with their own peculiar search tools. Such collections tend to be organized by place—and place turns out to be a more complicated idea than you might imagine when you start thinking about it in maps.

It's easy enough, for instance, to find a map of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and then start gathering historical versions of that same map like the 1948 one to the right that celebrated the university's centennial. But the UW is in a city called Madison, a county called Dane, a state called Wisconsin, a region (or multiple regions) called the Mississippi Valley or the Great Lakes or what have you, a nation called the United States, a continent called North America, a hemisphere called Western, a planet called Earth...and so on and on. Maps of all these nested places are relevant to the university campus depicted at right.

The wonders of maps are endless. Learn more about them here.

Return to Top of Page

Kevin Gibbons conducts an interview

Not all documents are in libraries or archives or on the Web. Some of the most compelling and important ones are inside people's heads.

Asking people what they know about a past person or place or event can teach you things about history that you can't learn in any other ways.

Research about the past based on interviews with living human beings is called "oral history." Interviews pose all sorts of intriguing challenges that can be quite unlike working with other kinds of documents—though the basic critical questions you'll ask when using any other kind of document apply to oral history interviews as well.

You shouldn't embark lightly on an oral history research project. It requires at least as much forethought and preparation as any other kind of historical investigation, and you'll need to do your homework if you want to do it right. But you shouldn't shy away from it either. Listening to someone share their memories about a topic you care about can be powerful indeed.

To learn more about doing oral history, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Graph of Wisconsin River Discharge Rates at Muscoda

You might imagine that the study of history is more about words than about numbers, but that's not really true, especially for those of us who are interested in past environmental change.

Many of the most important questions we ask about the past are implicitly about things that can be counted, even if that's not the way we first conceived of such questions. How did the diet of working Americans change in the nineteenth century? We know they ate more of certain foods in 1900 than they did in 1800—but how much more, and why? What kinds of documents will help us estimate how the relative shares of grains and meats and vegetables in American diets changed over time? At base, these are quantitative questions.

Moreover, many disciplines in the natural and social sciences have enormous contributions to make to our understanding of past change, and learning to read the findings of such disciplines requires a basic knowledge of statistics.

To learn more about using quantitative evidence, click here.

Return to Top of Page

Southwestern Wisconsin Landscape

Landscapes are among the richest, most complicated historical documents in the world, containing as they do layer upon layer of the past lives and natural processes that have left marks upon them.

Landscapes exist in the present, but they also contain countless remnants of the pasts that have given them their present form. Learning to read a landscape can take a lifetime—and is endlessly rewarding.

There's no one way to interpret or understand landscapes. A social historian will see quite different things in it than an economic historian will—to say nothing of what a geologist or ecologist will see.

That is why the craft of landscape reading is best done by adopting many different perspectives when experiencing and interpreting the place you're researching.

We've gathered some of our own favorite tips for learning to reading landscapes here. Have fun!

Return to Top of Page

History/Geography 932 Seminar, Fall 2008

We learned an enormous amount not just about research but about designing websites and working together as a team in building this on-line introduction to historical research.

If you're interested in learning more about how we built this website, click here.

Return to Top of Page

|