Learning to Do Historical Research: Sources

Manuscripts and ArchivesUnpublished, Unfiltered, Unfound

Jesse Gant

Brian Hamilton

Introduction

Travel with us through the huge but deeply rewarding world of primary research using manuscript collections. You will find an argument for why manuscript collections are worth the time, as well as insider tips for navigating the foreign country we call the reading room. See how manuscripts collections enhance and deepen your research questions and how they can help you write history you'll be proud of.

Table of Contents

What do your emails reveal about who you are? If strangers read your diary, how would it help them understand the choices you make? What do the scraps of paper in your room know about you that your friends and family do not? What could a boxful of the stuff you keep crammed inside your closet tell someone writing the story of your life?

Historians study the people of the past. Because they have neither time machines nor E.S.P., they need documents to help them gain a handle on what was going on in the minds of their subjects. Critical to this work are manuscripts.

Manuscripts are the unpublished papers of an individual or an organization. Think of these collections as history's own closet. Inside, you'll find things that are one of a kind—the unpublished, unfiltered, and in some cases, still unfound. Much of the material in manuscript collections comes from actual closets. Peeking inside, the historian crosses over the line between the public and the private. They provide us the best chance we have to see the world as the people we write about did.

Return to Top of Page

How to Find Manuscript Collections

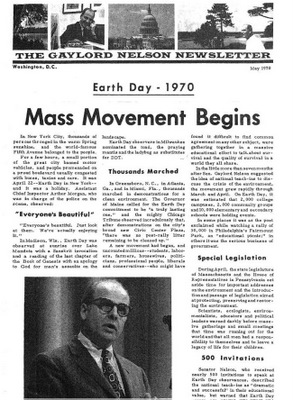

[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, www.noaa.gov; click to view larger image]

How do we go about finding a collection that can answer our research question? First, here's what we want to know:

What people and groups were responsible for starting Earth Day and how did they collaborate?

Here are the five things we did to find manuscript collections useful to our research question.

- Identify people. We wouldn't find a collection called “Earth Day” or “Environmentalism.” Archives sort personal papers under the names of individuals and organizations. In our early reading, the name of Senator Gaylord Nelson showed up often, so we searched for him.

- Identify dates. People live a long time. Organizations can outlive their members. Which years are most relevant to our question? We know Earth Day happened in April of 1970, so we zero in on a window of 1968 to 1972.

- Ask the local archivist. They are professionals, trained in the art of hunting down manuscripts. Ours pointed us to the online search engine WorldCat. There we limited our search to manuscript collections labeled “Gaylord Nelson” and the dates we chose.

- Use common sense. We found the Nelson Papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, Wisconsin. That's no surprise. Nelson was a senator from Wisconsin. An archive tends to collect material that aligns with its affiliation. So the papers of senators typically end up in their home-state archives and university professors' papers can often be found where they did their teaching. This isn't a hard-and-fast rule, but it's helpful to keep in mind.

- Try reference books. There are lots of great directories, in print and online, that describe the contents of archives. Look to our “To Learn More” section for suggestions.

Return to Top of Page

Navigating the Reading Room

Archives are a Foreign Country

Now that we have identified the Nelson Papers, we need to make our way to the collection. Archives have unique customs. Here we present five tips to help make your visit efficient and rewarding.

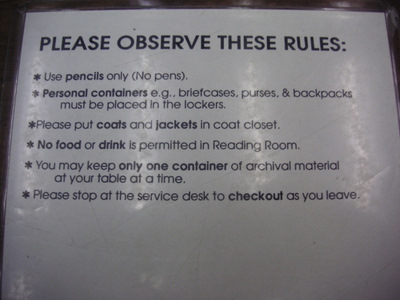

[Photo by Brian Hamilton]

- Learn the rules. Pens, food, drinks, and personal items will not be allowed inside. Depending on your local repository’s policies, you can bring things like cameras and laptop computers. Make sure that you check on the specific policies of the repository you're using before you visit.

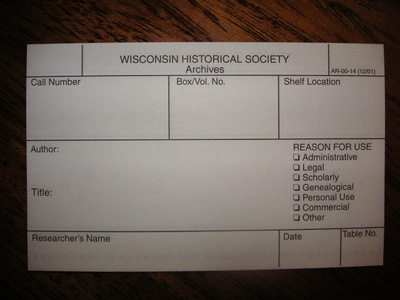

- Register. The archivists will ask you to undergo a process they call registration, which is meant to protect both you and the materials inside an archive. You may need to present a driver's license, contact information, and a photo ID.

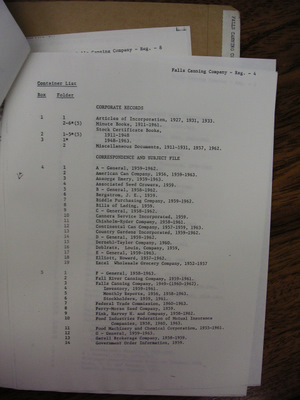

[Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

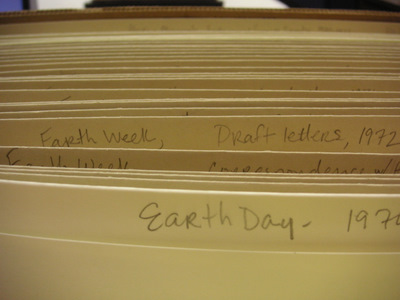

- Locate the finding aid. Archivists have devised a special tool for navigating manuscript collections called the finding aid. It outlines the important information about a collection, but also points you toward specific bits of information and materials within a collection. The Nelson finding aid is online. A quick search gave us several hits on “Earth Day.”

[Photo by Brian Hamilton]

- Fill out the call slip. A call slip helps the archivist locate your collection. Copy the information carefully from the finding aid. Turn it in to the archivists on staff.

- Plan ahead. If at all possible, do whatever you can to plan your visits in advance. You can email or call the staff to discuss hours and availability. We were surprised with some bad news when we asked for the Nelson Papers. One of our boxes was on loan to another institution. Had we made the effort to call ahead, we could have ensured that the materials we wanted to see were available.

[Photo by Brian Hamilton]

- Ask an archivist! If you are ever in doubt, ask for help. One of the best resources you can find is the archivist who actually processed the collection you want to work with. Often, this information is provided in the collection’s finding aid.

Return to Top of Page

Mining Manuscript Collections

[Photo by Brian Hamilton]

Now that we have requested the materials we want, we are ready to begin our search within the Nelson Papers. Experienced researchers share some good habits. Let's see some of those habits on display.

Take Good Notes

Even the highest-profile manuscript collection is less closely catalogued than any library. You can save valuable time, energy, and money by keeping a close record of the box and folder location of the materials you find. If you have not made a note of what you have seen, you may never find it again. Taking good notes will also help you cite and quote from materials in the future. Some archives allow personal scanners and digital cameras, while some do not. This is another great reason to email or call ahead.

Return to Top of Page

Ask Your Research Question and Lots of Others

We keep in mind our question: What people and groups were responsible for starting Earth Day and how did they collaborate? We’re keeping our eyes peeled for the names of people and groups in documents from the years before Earth Day.

[Photo by Brian Hamilton]

Opening one of the file boxes will reveal files with labels corresponding to what we saw in the finding aids. We can begin looking for things with explicit connections to Earth Day.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

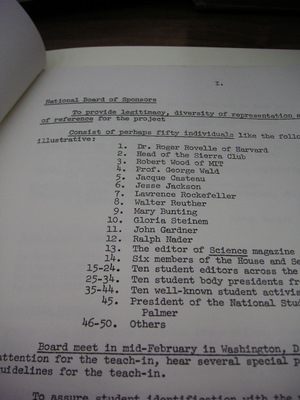

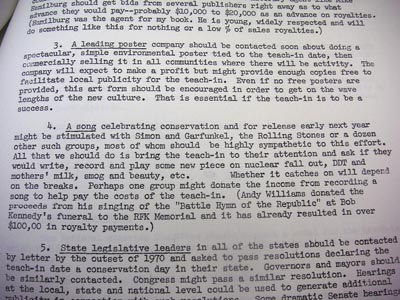

Soon enough, we find what looks to be a treasure, a “first draft” of a “Prospectus for a National Teach In On Our Worsening Environment.” Here's a chance to see Earth Day in its earliest conception. Who might have been involved? Could this teach us something about what they envisioned?

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton]

Right there, on the first page, we get a list of fifty potential participants the organizers wanted to bring together. We scribble down those names, for they might help answer the first half of our research question. Note that Nelson hoped the participation of these figures would “provide legitimacy” to the project. We’ve only been at it a couple minutes, and already we have found an incredibly valuable source. As we keep flipping, other things catch our eye.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

Even by simply skimming through the pages, we cannot help but notice a section proposing collaboration with Simon and Garfunkel or the Rolling Stones. That seems pretty cool. But since it seems more like brainstorming, we make a little note of it, but move on quickly.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton]

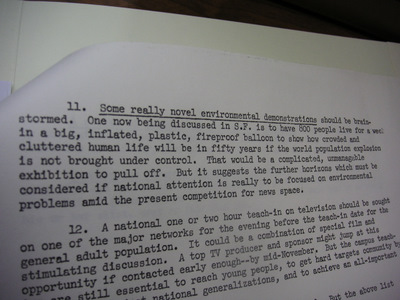

Two pages later there is a bizarre proposal for some sort of public spectacle where a bunch of folks would cram themselves into a giant balloon as a rendering of an overcrowded planet. Like the bit about the musicians, it's hard to ignore, but it doesn't seem relevant to our question, so we keep looking.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

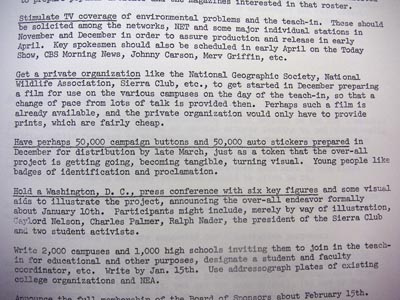

A couple pages later, we find plans to ally with several leading environmental organizations. That seems really useful, so we take careful notes. Immediately after, we notice a plan for thousands of buttons and bumper stickers to be distributed among “young people,” because they “like badges of identification and proclamation.” This sentiment strikes us as funny and odd. But since no specific people are mentioned, we don’t write anything down. Reaching the end of the prospectus, we explore new items in the folder.

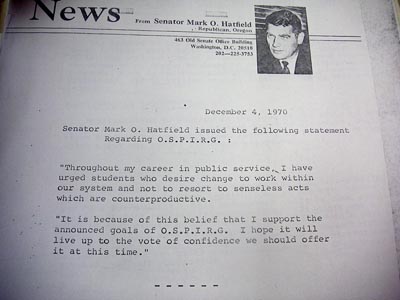

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

We find a press release from an Oregon senator. He's endorsing the work of some student group. We are struck by his repudiation of students who “resort to senseless acts which are counterproductive.” But the release is dated several months after Earth Day, so we put it aside.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton]

Then we find an issue of a newsletter with a cover story about the environmental movement. We notice the name Mark Rudd on the cover and recognize him as a famous student radical from the 60's.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

Inside, there is a striking picture of students in gas masks and a passage circled quoting someone in Nelson's office and celebrating “student agitation.” It’s pretty interesting, but doesn’t seem connected to Earth Day.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

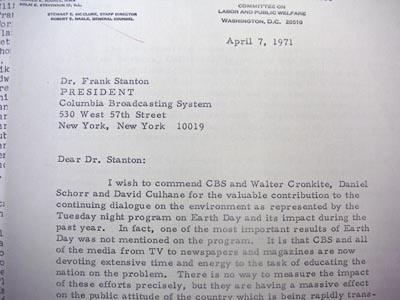

Then, we find a letter dated one year after Earth Day, which we almost ignore until we see it was written by the president of CBS. We begin reading it.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

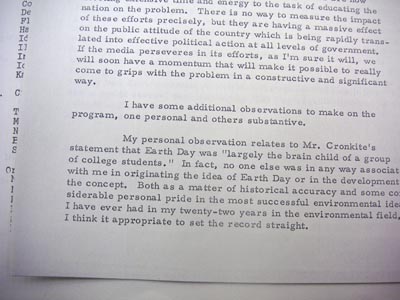

A passage quickly jumps out at us. Nelson refutes CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite’s comments crediting students with starting Earth Day. That surprises us, and we decide it might have relevance to our research question. So we record it.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

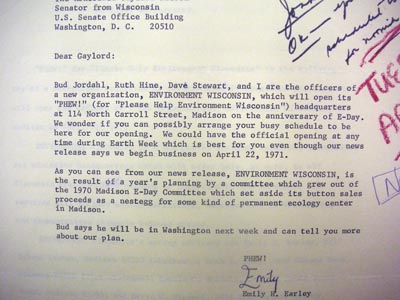

The next item in the file is a letter from a leader of a local environmental organization. Though it's from 1971, we decide to read it because it refers to an organization which might have played a role in Earth Day. There, in the second- to-last sentence, another reference to buttons! How bizarre. It seems the capital to begin this organization came out of button sales, possibly those same buttons proposed in the prospectus. What a strange connection. But, since it says this group wasn't around before Earth Day, it's not relevant to our research question....

Take notice! For the third time we have moved away from a document that interests us because it doesn't seem to connect to our research question. Meanwhile, what we've found that's directly relevant—two lists of names and organizations the planners wanted bring on board—excites us less and doesn't suggest how those parties interacted or even if they were involved. Plus, with Nelson taking all the credit in his letter to CBS news, the story might be less complex than we imagined; maybe it was just a one-man operation. Or, Nelson might not be a good person to look at if we're interested in collaboration and complexity.

Yet these materials raise lots of questions for us. We just haven't let ourselves ask them. Was there a generation gap in Earth Day? How united were the objectives of the students and adults? In what ways did its planners try to draw on the existing political networks of student radicals and youth culture? How did Earth Day's planners at the same time try to distance themselves from the youth movement? Were the planners successful in “legitimizing” their efforts in the eyes of the public? What role did mass media and popular culture play in popularizing Earth Day, and what was the meaning of the event in those arenas? And don't write off the importance of those buttons, for they could raise fascinating questions of their own about lots of under-explored topics.

Research questions change when you're inside an archive. That's because you get a better sense of what sorts of arguments the documents can support, and because manuscript collections are full of weird and wonderful things that insist on being explored. Make sure you care about the question you go in with enough that you won't immediately abandon it after reading the first document. But don't be afraid to let your question transform itself in dialogue with the documents. Whatever you do, keep track of this thought process on paper. New questions or discarded ones could represent future projects.

Return to Top of Page

Think Like A Narrator

You open another “Earth Day" folder and find something very exciting.

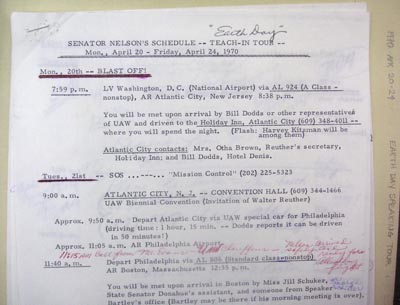

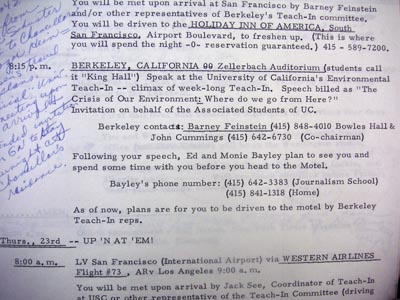

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

It's Nelson's itinerary for the week of Earth Day, a treasure trove for our question about institutional alliances and the role of individual actors. But it has another kind of potential, too. It could help us concoct the narrative of our argument.

Historians are storytellers. Manuscripts offer you some of the best tools to use to tell rich, detailed, exciting stories. For instance, this itinerary could allow us to model our whole argument as the story of Nelson's week, making arguments about the parties responsible for Earth Day as we follow Nelson's travels. The relationship between organized labor and environmentalism might come after a depiction of the United Auto Workers chauffeur picking up Nelson at his hotel, while our handling of government officials’ connections to student activists could begin with Nelson taking the podium at Berkeley.

Beyond constructing narrative, it's a good idea to keep close track of dates. Not only does it give context to the items you find, but it also allows you to see unexpected connections. When browsing the Nelson finding aid, for instance, we discover that at the same time Nelson was working on Earth Day he was fighting to get northern Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands designated as a national lakeshore. This gives us a fuller picture of Nelson's life at the time that can be obscured by the fact his papers are broken into folders by topic. That the two efforts were simultaneous also raises all sorts of questions about the role of land preservation in that year's teach-ins. Here, too, might be another opportunity for narrative, juxtaposing stories from one battle with those from the other.

Return to Top of Page

Little Things Are Big

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

Documents present material limitations. Very little American history was written on stone tablets, and even the names on those Puritan gravestones are eroding away. While the severity of obstacles will depend on the collection, the nature of paper records can easily raise your blood pressure. Even in the brand-new Nelson Papers there are rips that before long will be missing chunks. Indecipherable handwriting can give you fits, too. For the most part, we have to learn to live with what we have. (Almost everything that's ever been written down has not ended up in an archive, remember.) Keep track of gaps and uncertainties, for future research may give you new clues.

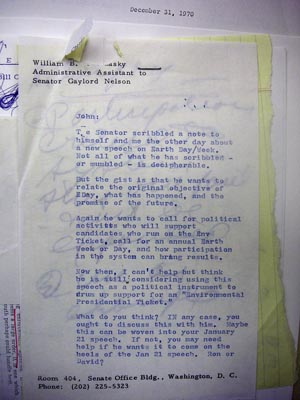

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

The paper nature of manuscripts has its upsides as well. Above all, people can write on it. And they can write on the same piece of paper again and again over time. Lots of the correspondence in this collection has a second, third, and fourth life given to it by notes in the margins. The jottings of his secretary can, for instance, give us a better picture of his administrative world.

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Brian Hamilton; click to view larger image]

Find arguments in the details. We find a copy of an article from a science journal. We're in the archive because we're looking for unpublished material. What could we use a journal to prove, except that Nelson died with it in his possession? Maybe nothing, until we discover a smattering of pen marks. He has circled text and even put a question mark next to a passage heralding the contributions contemporary scientists have made “to man by calling attention to his environmental problems.” Perhaps Nelson, after years of battling with chemical industry scientists did not share the sentiment? We can't prove an argument with a question mark, but it might help us look at other evidence differently.

Return to Top of Page

Sniff Out Paper Trails

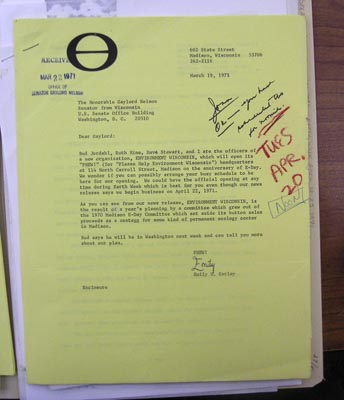

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

Documents point you to the next destination. You read a letter from a group called People's Response on Better Environment (PROBE), thanking Nelson for coming to the University of Southern California (USC) and promising to send a tape of his lecture. A note in the margins confirms the receipt of that tape. We could look for it elsewhere in the Nelson collection. We could also search USC’s archives for PROBE's records.

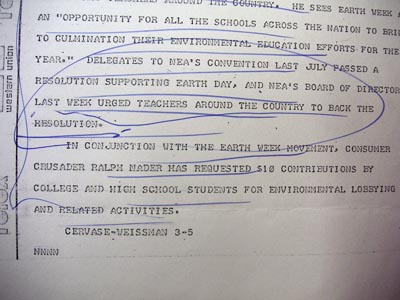

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

We find a telegram recounting the Earth Day activities of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and Ralph Nader. So we can think about mining the NEA's records at the National Archives and a quick WorldCat search reveals that the papers of Nader's Environmental Action Coalition are housed at the New York Public Library. Then we remember all those other names that joined Nader's on the first list of potential participants, and suddenly there are lots of collections of interest, from the papers of Jacques Cousteau to Gloria Steinem.

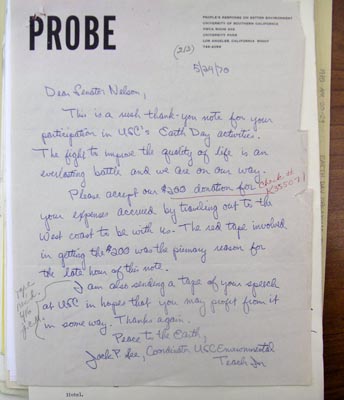

[Gaylord Nelson Papers, Photo by Jesse Gant; click to view larger image]

We return to Nelson's Earth Week schedule and see names everywhere. Those are all research leads. He was hosted in Berkeley by Barney Feinstein and Ed and Monie Bayley. While nobody may have collected their papers, they very well may still be alive and could be subjects for an oral history.

Time and money will constrain the breadth of your project, but these are the sorts of thoughts to be having to keep your research alive. Always think about the people and organizations you encounter in your secondary readings. Ask: Might these people and groups have left behind a paper trail?

Return to Top of Page

Always Consider Your Friends and the Future

In every collection you work with there will be much that is of no use to you, but that doesn't make it useless. You are in a unique position to direct the research of others into corners they would never think to explore.

Say we have a friend researching the history of the population debate. She might be up to her ears in the writing of the Stanford population biologist Paul Ehrlich. Even if she looked at the Nelson Papers, she might not look at the Earth Day stuff. Even if she were to look at the Earth Day stuff, she might not open the right folder or scan the right page to discover that the planners of Earth Day dreamed of putting eight hundred San Franciscans in a giant balloon for a week. Whether it became a centerpiece of one of her arguments, an anecdote opening a chapter, or simply an off-hand comment she makes when giving a talk, we can do her a favor by passing it along.

Likewise, explain your research interests to everyone you know who spends time mucking through manuscripts. They can keep their eyes peeled for things of use to you.

Return to Top of Page

Even with the best advice, figuring out how to have success in an archive requires on-the-job training—both self-education and learning from archivists. But if you're about to work with manuscripts for the first time, here's an exercise to prepare you for what's in store.

Visit the University of Virginia's Valley of a Shadow website [http://valley.vcdh.virginia.edu]. This contains a wide array of documents from Franklin County, PA and Augusta Country, VA for the years 1859 to 1870. You'll see from the “floor plan” table of contents that the University of Virginia's archivists offer both published documents (like newspapers and census records) and unpublished material (like letters and diaries, as well as the records of churches and the Freedman's Bureau).

Spend fifteen minutes browsing Augusta County newspaper articles from after the war that are organized around the topic “Agriculture/Commerce/The Economy.” Then spend the same amount of time perusing, from the same period and place, the diaries of Francis McFarland and Joseph Waddell as well as the letters of the Nadenbousch and Smiley Families.

Contrast the content of the newspapers with that of the letters and diaries. How are the same subjects presented differently in the two different types of documents? What kinds of people are visible in the personal papers and distorted, less visible, or invisible in the newspapers? What sorts of research questions might you be able to ask only of the manuscript material? What's frustrating about working with the manuscripts? How might you be able to get around the obstacles they pose?

This exercise helps you understand the potential and constraints of using manuscript collections. Experience will help you see what manuscripts alone can offer you as well as the virtue of putting different types of documents into conversation.

.

Return to Top of Page

- Do get to know your archivists. Ask plenty of questions and develop good relationships

- Do take more detailed notes than you think you'll need

- Do seek out help from the archivists before, during, and after your visits

- Do always be thinking of other documents you could explore next

- Do think creatively

- Don't break the reading room rules!

- Don't let holes in the collection or material you can't understand derail you

- Don't try to smuggle banned substances into the archives: You can harm much more than the historical record!

- Don't come to the archives without questions. Archivists can only do so much to help you move along in your research

- Don't waste time. Your visits cannot last forever

Return to Top of Page

Wouldn't it be great if there was one place you could look to find a list of every archive in the country and what it has in it? Compiling such a thing is like trying to collect one needle from every bail of hay in America. The first serious attempt was made by Philip Hamer in A Guide to Archives and Manuscripts in the United States (1961). He sent questionnaires to archives of all shapes and sizes asking what sorts of things a researcher could find there.

Hamer's volume was updated in 1978 and again in 1988 by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) under the name Directory of Archives and Manuscript Repositories in the United States. You can find the names of 4,550 archives and read detailed descriptions of the contents of the vast majority. The summaries are organized by state (and also include D.C., Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the Mariana Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone), but the back of the book also has the names of all the archives organized by type: corporate, local and state government, local and state historical society, museum, medical institution, organizational, public library, religious institution, and university. They cast a wide net, profiling any place that preserves information dating from as early as 1450. In addition to manuscript collections, they also list repositories of photographs, sound recordings, movies, architectural drawings, and microfilms for documents that no longer exist or aren't publicly available.

It's an entertaining book to flip through and full of surprises. You'll learn that if you want to take a look at the papers of Artic explorer Robert Burton, you'll need to truck to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. To examine piles of pictures of the moon, set your sights on Houston's Lunar Science Institute. From there, it's not to far to Roswell, New Mexico, where you'll need to go if you're curious about atomic rocket scientist Robert Goddard, whose letters, lecture notes, and blueprints, reside in that city's Museum and Art Center. If you are interested rather in slightly more primitive forms of aerospace technology, waiting for you are the records of the Sport Balloon Society of the United States of America, preserved in perpetuity in Indianola, Iowa. Becoming an archive addict is not unheard of, and taking a peek at this volume for ideas of places to explore in your area or on your next trip will be worth your while. One warning: Having both books in front of you is, unfortunately, necessary. The Directory often leaves out detailed descriptions of archives, telling the reader instead to “see Hamer.” Without both books, you might never learn that the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association is in possession of George Washington's 1797 diary.

A more recent book that does something similar is Guides to Archives and Manuscript Collections in the United States: An Annotated Bibliography (1994). Here editor Donald L. DeWitt attempts to list and annotate the names of published directories of individual archives and published finding aids to particular collections. So it's a guidebook to guidebooks. What's most useful about it is that it is organized not by state but by topic. Sections include “Fine Arts Collections,” “Ethnic Minorities and Women,” “Business Collections,” and even “Foreign Repositories Holding U.S.-related Records.” Even more helpfully, it breaks those down into subgroups like “Radio/Television,” “Native Americans,” "Agriculture and Forestry,” and so forth. So the citation for the guide to the American Philosophical Society's collection of Darwin's letters appears next to that for the National Air and Space Museum's Space Astronomy Oral History Catalog.

A more recent, but short and less useful, bibliography of this sort is the NHPRC's Historical Documentary Editions, available as a free .pdf at http://www.archives.gov/nhprc/projects/publishing/catalog.pdf.

Return to Top of Page

Directories on the Internet

There isn't yet any place online that offers exactly what the books above do. Lexis-Nexis's Archive Finder [http://archives.chadwyck.com/home.do], a subscription search engine combines the content of two books: The National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections and its British and Irish equivalents. Should you have a particular manuscript collection in mind, as we did with the Nelson Papers, a web search like this will be your most efficient route. Ask your librarians or archivists if their institution subscribes to such a resource.

The closest thing on the Web offered for free is the impressive attempt by the University of Idaho. On their site, Repositories of Primary Sources [http://www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/special-collections/Other.Repositories.html] they have set up a gateway to websites of archives all around the world. Like Hamer, they group archives by state, though it's much more difficult to browse because it includes only a link, forcing you to then go sifting through the archive's website to learn about its holdings. On its “Additional Lists” page it points you to other sites that compile lists of archives around particular subjects, like “Map Libraries” and “History of Science.” Be warned that though the site appears to be actively updated, it's clearly a bare-bones operation and broken links are common.

The Forest History Society's website features a superb Guide to Environmental History Archival Collections [http://www.foresthistory.org/Research/archguid.html], allowing users to search over 7,000 collections at nearly 500 repositories. The American Society for Environmental History's website includes a page for environmental history archives and libraries [http://www.aseh.net/resources/lib-arc/]. At present it's slim pickings, but what’s there at present—links to online finding aids for EPA, NOAA, and Fish & Wildlife's Conservation Library—is all worth being aware of.

The National Park Service offers Park Museum Collection Profiles [http://home.nps.gov/applications/museum/museumselectpark.cfm]. It includes entries for each of the hundreds of properties the NPS manages, offering capsule descriptions of the documents and artifacts kept at those sites. More immediately valuable is their “Treasures of the Nation” directory, which includes scans of exciting photographs, documents, and material culture from those park museums. Unfortunately, there are under 100 total items included and they are organized alphabetically not by author or subject but by type of document. Although all you can do is browse, there are plenty of exciting things to look at. On the “L” page you can jump from a picture of George Washington Carver's laboratory instruments to a scan of a Frederick Douglass shopping list.

Return to Top of Page

Books on archival research

Researcher's Guide to Archives and Regional History Sources (Library Professional Publications, 1988).

Edited by John C. Larson and consisting of essays by fifteen archivists and librarians from important collections around the country, this volume covers in much greater detail the ground we do here (with chapters on “What Every Researcher Should Know about Archives” and “General Use of an Archive”) as well as useful specialized topics (like “Cartographic Sources” and “Business Records”).

Archival Strategies and Techniques (Sage Publications, 1993).

Part of the many-volume Qualitative Research Methods Series, this guide is aimed at social scientists of all stripes. Its advantage over the Researcher's Guide is that it is written by one author and attempts to be comprehensive in its scope.

Archive Stories: Fact, Fictions, and the Writing of History (Duke, 2005).

Historians enjoy sharing their tales from the trenches, and this is only the most recent collection of such accounts. Sixteen scholars share first-hand accounts of encounters with archives around the world.

Return to Top of Page

Archives to have on your radar

As researchers gain experience they develop in their minds their own directory of the archives that hold manuscript material of interest to them. Below are some that make it into the memory banks of most environmental historians early on.

The Denver Public Library (Denver, CO) [http://history.denverlibrary.org] is a monumental repository of documents from the American West. Equally indispensable is its collection on conservation, notably including the papers of William Vogt, Hugh Hammond Bennett, Estella B. Leopold, Morris Udall, the American Bison Society, and the Wilderness Society. Many of its most-used finding aids are online. In its collection also are over 600,000 images, a fair minority of which have been digitized and made available on its website. Its new annex, the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library, is the place to go with any questions about the cultural history of African Americans in the Rocky Mountain West.

The Wisconsin Historical Society [http://www.wisconsinhistory.org] library and archives (Madison, WI) together make up the world's largest collection solely devoted to the history of North America. Among its many merits, its archivists began collecting material from Native Americans before any other institutions and its newspaper repository is second only to the Library of Congress. It has been remarkably successful in digitizing large elements of its local newspaper, photographs, and manuscript collections for use on the web. A quick search of its website is well worth your time—especially the subfield called “Wisconsin Turning Points,” which highlights some of the jewels of the Wisconsin Historical Society manuscript collections in digital form.

The National Archives [http://archives.gov/] preserves, in D.C. and at its regional branches, between one and three percent of documents produced by the federal government. That has amounted so far to four billion pieces of paper and almost that many electronic records. While structurally not designed for manuscripts, the National Archives and Records Administration also oversees presidential libraries for every U.S. president after Coolidge. Aside from including elaborate, well-funded museums, these are the official homes for the papers of those presidents, but their holdings also included a range of other material, from film reels to family heirlooms. If you're looking for the papers for someone high-up in Washington who didn't work in the Oval Office—say, Mary Todd Lincoln or New Deal Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes - look to the Library of Congress [http://www.loc.gov] where those manuscript collections are two of 61 million.

While Harvard's is the largest of all university libraries in the United States, the manuscript collections at Yale's Beinecke Library [http://www.library.yale.edu/beinecke] are probably more useful for studying American environmental history. They have extensive collections on western overland migration, mining in the West and Alaska, the modern American Indian movement, Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker's Unions, and WWII Japanese internment. And, besides being the repository for the papers of Rachel Carson, you can also leaf through the manuscripts of Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, W.E.B. Du Bois and nearly all the major figures of the Harlem Renaissance, Georgia O'Keefe, James Fenimore Cooper, Robert Penn Warren, and Sinclair Lewis. Should you get bored, there's also a Gutenberg Bible.

Many major archives do include online collections on their website. While these are no doubt useful, they should not be mistaken for anything more than the smallest fraction of the archive's holdings. Of course, a small fraction of a massive holding is nothing to sneeze at, and that's what you find at the Library of Congress's American Memory Collection [http://memory.loc.gov]. Now including over 100 thematic document groupings, the site will captivate environmental historians with its broad survey (“Travels in America, 1750-1920”) and deep examination (“Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia”).

Return to Top of Page

|