|

|

|

||||

Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer

|

Author: Mark Fiege |

Author: Stephen Mihm |

Claim: “Unlike other examples of southern currency from the post-bellum period, the $1 note features no steamboats or locomotives, important symbols of mechanization, industrialization, and corporate power. Instead, the note’s three primary scenes suggest an idealized world of small agrarian producers.” |

Claim: “…this piece of paper is doing far more 'work' than merely facilitating commerce in South Carolina. In ways both subtle and not, it is operating as a medium for the exchange of racist propaganda of the sort that would lay the foundation for the overthrow of Reconstruction in that state during the 1870s.” |

To find evidence to support your claim, first imagine the primary and secondary documents that will provide the convincing evidence you need to win over readers to your ideas. It will be helpful to differentiate between primary and secondary sources as you build your bibliography. To help make the distinction, we have included a description below from our What are the Documents? web page. Please consult this page for a more detailed description. Our discussion of evidence below is also based on the book A Pocket Guide to Writing in History by Mary Lynn Rampolla.

The primary source is the one that has the closest relationship in both time and space to the subject you are studying. This often implies a documentary relationship, of course, but even this definition is flexible. We tend to think of an early conservationist’s diary as a primary source, but the conservationist’s clothing, routes of travel, and work locations could also be used as a primary source.

The secondary source addresses themes or subjects directly related to or explicitly “about” a primary source. Historians, journalists, politicians, and others who might cite primary sources may comment on, interpret, or otherwise summarize the stuff of primary material in order to condense it or build and argument from it. This process yields work or writings we would then call secondary to the primary material.

Clearly there is no specific formula for the ratio you should have between these two types of sources. For beginning researchers, however, it is easy to overlook primary documents because they typically take more effort to locate and interpret. In the end, the time spent finding them will be worth it for their potential in developing a compelling narrative and for the depth they provide to your analysis.

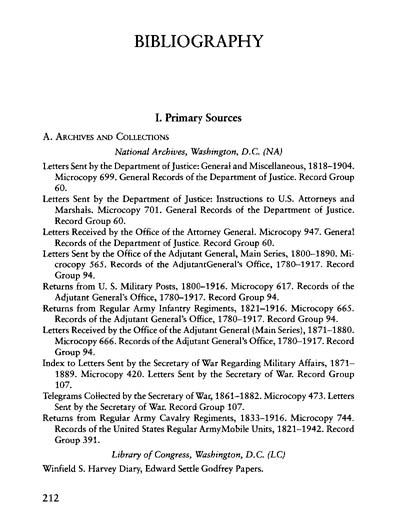

We can turn to our South Carolina currency example above for some guidance. In one of Mihm’s sources, State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina, author Richard Zuczek divides his 13-page bibliography evenly between primary and secondary sources.

The first page of primary sources from State of Rebellion by Zuczek, 1996.

In your own research, you should incorporate primary sources such as maps, newspaper articles, or government documents. These will provide powerful firsthand accounts of the period and place you are studying, but their quality must be verified. When locating primary documents, pay close attention to the following questions:

Secondary sources help you get a feel for how scholars interpret past events. Reading a variety of secondary sources demonstrates the way scholars use primary evidence to make competing claims. Key questions to ask include:

Situate your sources in the larger body of writing about your topic and be aware of major events that occurred around the document’s publication. If an author has published multiple journal articles about a similar topic, it is best to consult the most recent version to get a sense of their latest views on the subject.

Do not take this to mean, however, that only the most recent scholarship is the most useful or valid. Many older works contain insights that may be overlooked because they are viewed as outdated. Even if one part of a source’s scholarship is in fact deemed outdated or unhelpful, there may be nuggets of wisdom hiding in these works. Finally, comparing older works with more recent ones gives you a feel for how people’s interpretations of historical events have changed over time.

Also examine your secondary sources to determine if the claims of the author are justified by the evidence provided. Are they making a broad conclusion that is unwarranted by the amount of evidence provided? Do the conclusions flow logically from the evidence provided?

Finally, note how the claims laid out in each of your sources compare to others on the same topic instead of relying on a single source. What kinds of evidence do different authors use when examining the same topic? Do they come to different conclusions even if using similar sources? Why might that be the case?

Fiege and Mihm’s essays demonstrate how one can construct very different arguments when interpreting the same historical document. Both authors above provide multiple secondary source citations from reputable academic journals and books that are by scholars in the fields of cultural, economic, and environmental history. Each author, however, relies on different sources that lead to a divergence in the questions they ask and the evidence they seek. Aspects of their argument are included below as an example:

Author: Mark Fiege |

Author: Stephen Mihm |

Claim: “Unlike other examples of southern currency from the post-bellum period, the $1 note features no steamboats or locomotives, important symbols of mechanization, industrialization, and corporate power. Instead, the note’s three primary scenes suggest an idealized world of small agrarian producers.” |

Claim: “…this piece of paper is doing far more 'work' than merely facilitating commerce in South Carolina. In ways both subtle and not, it is operating as a medium for the exchange of racist propaganda of the sort that would lay the foundation for the overthrow of Reconstruction in that state during the 1870s." |

Evidence 1: The blacksmith represents pre-industrial muscle power. “With his meaty arms, stocky body, and foot resting on a stump next to an anvil, the blacksmith conveys a sense of organic muscular power. Although the picture does not show horses and oxen, other sources of muscle power, it implies their presence.” |

Evidence 1: The blacksmith is in an unusual pose, deliberately chosen by the financial institution for its symbolism relative to the others shown. Most 1850s blacksmith images on money depicted action. This image is unusual because it shows “an overseer, one who glares down at the slave—or former slave—picking cotton.” |

Evidence 2: The man picking cotton is the “most enigmatic” of the three images and could be interpreted to represent an independent yeoman or a subordinated race. He appears to be well dressed, well fed, and strong, and he may own the distant house. But, this image might “have been intended to reassure small white producers that nominally free African Americans still would accept an inferior place in the cotton fields.” |

Evidence 2: The central image evokes pre-Civil War slave labor. The Mechanics and Farmers Building and Loan Association that printed the note adopted a common post Civil War practice in the South of choosing “an obsolete image that harkened back to a labor system destroyed by that war.” |

As an environmental historian, Fiege cites sources that consider both human and nonhuman historical context. His 13 sources range from “Does Nature Always Matter? Following Dirt Through History” by Ellen Stroud to A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Steven Hahn. Mihm’s training in cultural and economic history leads him to a narrower focus on human relationships and institutions. His 11 sources include Obsolete Paper Money Issued by Banks in the United States, 1782-1866 by David Bowers and Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction by Thomas Holt.

It is easy to ignore arguments that may contradict your own preconceived notions of how the world works. Ideally, however, conclusions are made only after carefully considering multiple explanations. Showing that you have thought about a problem from multiple points of view before coming to a conclusion will demonstrate to your readers that you have not ignored potential weaknesses in your argument. Moreover, if in your writing you treat with respect the ideas of others with whom you disagree, you are more likely to convince those authors (and readers who share their views) that your ideas are worth considering. Rather than just “preaching to the choir,” you may actually change readers’ minds.

How could you use the two arguments from the South Carolina currency example to practice considering alternate viewpoints? If you were citing these authors in making your own claim about the bank note’s symbolism, consider which argument is most compelling to you. Is Mihm justified in making such an unwavering and strong claim? Should Fiege take a stronger stance when interpreting the central image of the cotton picker? By citing the two authors, examining their sources, and developing your response to their arguments, you have shown that you have considered multiple interpretations in making your own argument about the bank note’s symbols.

A helpful way to learn how to construct an argument is to study how others do so. Two sources to consult in this regard are book reviews and the “letter to the editor” section of newspapers, magazines, and journals. Writers in these sections of newspapers or magazines often engage in concise analyses of an argument put forth by a journalist or author.

In the case of book reviews, a useful exercise after reading a book on your topic is to write down its main claims, the evidence to support the claim, how the author addresses alternate explanations, and the author’s conclusion. Then, consult a book review and see how an authority on the subject interprets the author’s argument. Over time, you will get a feel for how to identify the parts of an argument and, by observing the quality of others’ arguments, how to construct a good argument yourself.

Two useful sources for quality book reviews include The New York Times online “books” section and the Website for Powell’s Books in Seattle. Each has links on their sites for book review databases that go back several years. On the New York Times’ Webpage (www.nytimes.com), there is a “Books” link under the “Arts” section. At the top of the books section is a search window for all book reviews since 1981.

Once you’ve gotten to the stage where you’ve collected the evidence to support your claim, it’s time to think about how you’ll be communicating your ideas to an audience. You’ll want to consider not only the way in which you’ll convey your evidence, but also how you’ll bring your readers with you through your argument. Some styles will suit different argument structures better, and you should also consider the needs of your audience as well, and so you’ll want to think about your voice and organizational techniques simultaneously.

A narrative is simply a description of a sequence of events. Both fiction and non-fiction writers use story-telling devices not only to engage readers and communicate their values explicitly, but also to guide the reader through a complicated argument. The narrative choices you make as a writer will influence how readable your prose is, or even whether your hard-earned arguments are read at all. Writers may also employ narrative voices or techniques unintentionally, and so reading an argument as a narrative detective can offer new insights.

Narrative elements exist on several levels throughout a text:

The facts: The Grand Canyon was formed over six million years by the Colorado River in rock nearly two billion years old. Pueblo peoples inhabited the region for hundreds of years, but were certainly not the first humans to settle in the region. Garcia Lopez de Cardenas is believed to have been the first European to have seen the canyon in 1540, and over three hundred years later John Wesley Powell made the first recorded expedition down the river. In 1919, it became one of the first national parks in the United States, largely due to the efforts of Theodore Roosevelt.

Colorado River in Grand Canyon at Mid-Day

Wikipedia Creative Commons, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Canyon_midday.jpg

How would one go about telling the story of the Canyon? You don’t necessarily have to start at the beginning; while stories are often told chronologically, narratives can follow a number of different paths. You might consider beginning with the park’s creation in 1919, outlining its significance in the American conservation movement. You may choose to begin by imagining with de Cardenas as he first beheld one of the earth’s geological wonders, and his role in creating the mythology of the New World.

Chronological order isn’t essential to clarity in prose, but is a common template used in writing because it’s logical and easy to follow. It’s also predictable, which makes it less interesting, and may not be the best way to structure your argument, as with the Grand Canyon example above.

Deciding on what narrative arc to use can be intimidating early on. Create an outline before you begin writing, and use it to organize the evidence for your argument under the headings. Read through your outline often as it develops; use this to check if your narrative arc is easy to follow and is appropriate to your argument. Keep your outline close by during the writing processes; it’s your roadmap, and will help you keep a complicated structure clear.

Narrative devices that help guide your readers are the signposts pointing the way through a complex argument. Tell a reader where you’re going before you begin the argument, much as you would consult a map before you get in the car (this roadmap is essentially your narrative arc, taken from your outline). Signposts guide the reader from point to point along you’re the map, and they help remind them where they’ve come along the way.

A Roman mile marker

WIkipedia Creative Commons, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Campidoglio_-_il_miliarium.JPG

Sentences often contain signposts— a sentence opening with a word like but, however, until, or first is giving the reader a clue about the argument they’re about to read.

Metaphors, stories, or other devices can be used throughout a text to guide a reader through a complex argument, especially one that returns or cycles back to an early point. Readers will know that a key point or evidence is related to an earlier discussion much more readily if you signpost through the discussion. Literary techniques such as foreshadowing are also effective signposts.

The ways in which we write about nature can often be just as significant as what we’re saying; environmental historians grapple not only with the events of the past, but also the ways in which people experience and interpret those events. Environmental historians are interested not only in the relationship between humans and nature, but also how the ways in which scholars write about that relationship reflect their attitudes and values.

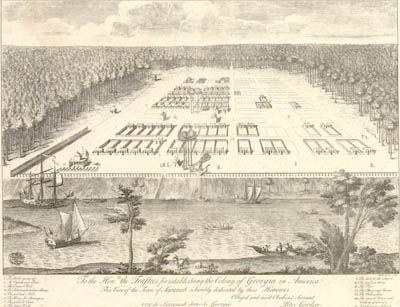

Remember that writers may or may not be aware of their narrative choices: in his essay Technology, Nature, and American Origin Stories, David Nye refers to a “master narrative” in American environmental history. Nye describes a narrative arc in which European colonists arrived in what to them was an Edenic New World (what he terms “first creation”), but then subsequently strove to improve it (“second creation”) by building farms, water mills, and estates.

Savannah Colony

Wikipedia Creative Commons, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/7/7e/SavannahColony.JPG

This meta-narrative became a lens through which Americans experienced nature; they told stories, interpreted those stories, developed a conservation ethic, and critiqued that ethic through this and other lenses. The rose-tinted glasses of early American land use were colored by Americans’ religious beliefs and cultural history, coming from the largely resource-depleted Europe to a land of seeming eternal plenty. Events like the extinction of the passenger pigeon and the Dust Bowl later made those glasses brown, however, and the narrative shifted to one of environmental decline and ultimately recovery.

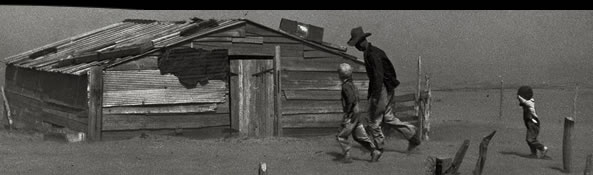

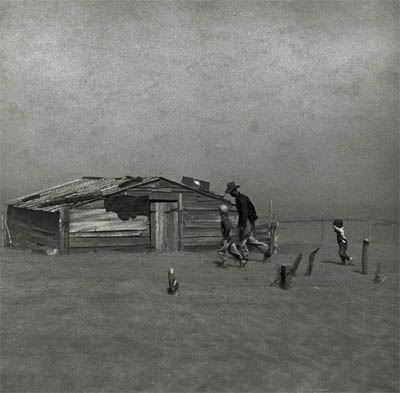

The two passages below, discussed by William Cronon in his essay “Nature, History and Narrative,” illustrate the relevance of meta-narrative to environmental history. These were taken from two books that came out in 1979 about the Dust Bowl, and each has a very different narrative approach:

In the final analysis, the story of the dust bowl was the story of people, people with ability and talent, people with resourcefulness, fortitude, and courage….The people of the dust bowl were not defeated, poverty-ridden people without hope. They were builders for tomorrow. During those years they continued to build their churches, their businesses, their schools, their colleges, their communities. They grew closer to God and fonder of the land….Because those determined people did not flee the stricken area during a crisis, the nation today enjoys a better standard of living.

---Paul Bonnifield, The Dust BowlThe Dust Bowl was the darkest moment in the twentieth-century life of the southern plains. The name suggests a place – a region whose borders are as inexact and shifting as a sand dune. But it was also an event of national, even planetary significance. A widely respected authority on world food problems, George Borgstrom, has ranked the creation of the Dust Bowl as one of the three worst ecological blunders in history....The Dust Bowl…was the inevitable outcome of a culture that deliberately, self-consciously, set itself [the] task of dominating and exploiting the land for all it was worth.

---Donald Worster, Dust Bowl

Dust storm in Cimarron County, Oklahoma

Wikipedia Creative Commons, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d4/Dust_storm_CimarronCounty_OK.jpg

You should notice immediately that two authors writing about the same subject have drawn very different conclusions about the meaning of the Dust Bowl. Is the story of the Dust Bowl one of an ecological blunder, or of human resilience in the face of a natural disaster? Is the story about humans, or the landscape they inhabit, or both? Was it an “inevitable outcome” of human land exploitation, as Worster suggests, or did it inspire people to become “fonder of the land,” as Bonnifield writes?

The answer is complicated, because it depends not on whose sources (Worster’s or Bonnifield’s) are better, or who offers a better argument. Both Worster and Bonnifield have set out to tell a particular story about the Dust Bowl, and each is expressing a particular set of values. Each writer is employing a separate narrative to describe the same event; each is essentially telling a story about something that actually happened, but the stories they have chosen to tell are quite different. Each employs evidence, and some of that evidence may even be the same for both arguments, but the resulting narratives are quite different.

When reading your documents, consider the narrative choices being made by the writer, whether they are used intentionally or not. When constructing your own argument, consider what your narrative choices reveal about your intentions and values, and whether you would like those to become an overt part of your argument. Recall the currency example above; Mihm and Fiege were not only using different kinds of evidence to support their claims, but were telling different stories about the post-bellum American South. Coming from different disciplinary backgrounds, they are participating in two different meta-narratives about the past—post-war pastoral idealization in Fiege’s argument, and in Mihm’s case, the story about the racial tensions that would ultimately derail Reconstruction.

You don’t have to sacrifice academic integrity in order to write lively and accessible prose. You can draw in your readers and maintain their interest in your argument by providing them with the incentive to keep reading. This is often most important in the opening paragraph of a piece of work, such as this discussion of the now-extinct passenger pigeon by Jennifer Price:

They say that when a flock of passenger pigeons flew across the countryside, the sky grew dark. The air rumbled and turned cold. Bird dung fell like hail. Horses stopped and trembled in their tracks, and chickens went in to roost. “I was suddenly struck with astonishment at a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant darkness,” the ornithologist Alexander Wilson wrote after he encountered a pigeon flock along the Ohio River in the early 1800’s: “I took [it] for a tornado, about to overwhelm the house and everything around in destruction. “ Wilson sat down to watch the flock pass over, and after five hours, he estimated that it had been 240 miles long and numbered over two billion birds.

Notice Price’s choice to begin not with the facts — such as a reference to a 240-mile-long flock of billions of birds — but with a descriptive, story-telling device: “They say…” As readers, we are drawn into the facts with an appeal to our senses — rumbling and darkness — and even a little of the fantastic — bird dung falling like hail. Price could just as easily have begun with the bare facts about the bird, or even an emotional case for our interest in what has become an iconic extinction event. Price’s choice to open with an anecdote accomplishes the seemingly impossible by making us feel as though we were there, when in fact not even Price herself has witnessed the event. Without sacrificing journalistic integrity, she shows us that she’s drawing from primary documents rather than personal conjecture.

As the Price example demonstrates, it is important to hook your readers early with engaging prose. In addition, your introduction should convince readers that the rest of your argument is worth considering. If you turn off your audience early on, they may never look at the rest of your work, even if it has impressive insights. Think of times when you have put a book down in frustration and never resumed reading it. What was the reason for doing so? Did the author rely on jargon that was hard to understand? Did the author dismiss viewpoints that you held without adequately explaining why?

Now imagine times when you have been drawn into a book and could not put it down. Consider how the author Michael Pollan grabs his readers’ attention in his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, both with the progression of chapter titles in his table of contents and with the very first paragraph:

What should we have for dinner?

This book is a long and fairly involved answer to this seemingly simple question. Along the way, it also tries to figure out how such a simple question could ever have gotten so complicated. As a culture we seem to have arrived at a place where whatever native wisdom we may once have possessed about eating has been replaced by confusion and anxiety. Somehow this most elemental of activities—figuring out what to eat—has come to require a remarkable amount of expert help. How did we ever get to a point where we need investigative journalists to tell us where our food comes from and nutritionists to determine the dinner menu?

Pollan starts off with a familiar question that most of us ask on a regular basis, and then moves on to make the claim that modern food supply systems have led recent generations to lose the connection to their food . As an investigative journalist, he spends the rest of his book visiting places involved in food supply, observing them, interviewing people at these locations, and sharing his insights about how our society got to that point.

It is important to note how Pollan uses narrative to structure his argument throughout the entire book. He chose to anchor his book around four meals that he purchased or prepared for family and friends. He then investigated how the food was grown and prepared in each case. This approach provides a storyline that links all of the book’s three sections and twenty chapters:

|

Table of Contents |

|

|

Introduction : our national eating disorder |

1 |

|

|

|

I |

Industrial: Corn |

|

1 |

The plant: corn's conquest |

15 |

2 |

The farm |

32 |

3 |

The elevator |

57 |

4 |

The feedlot: making meat |

65 |

5 |

The processing plant: making complex foods |

85 |

6 |

The consumer: a republic of fat |

100 |

7 |

The meal: fast food |

109 |

|

|

|

II |

Pastoral: Grass |

|

8 |

All flesh is grass |

123 |

9 |

Big organic |

134 |

10 |

Grass: thirteen ways of looking at a pasture |

185 |

11 |

The animals: practicing complexity |

208 |

12 |

Slaughter: in a glass abattoir |

226 |

13 |

The market: "greetings from the non-barcode people" |

239 |

14 |

The meal: grass-fed |

262 |

|

|

|

III |

Personal: The Forest |

|

15 |

The forager |

277 |

16 |

The omnivore's dilemma |

287 |

17 |

The ethics of eating animals |

304 |

18 |

Hunting: the meat |

334 |

19 |

Gathering: the fungi |

364 |

20 |

The perfect meal |

391 |

Table of Contents from The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan

Organizing the book around the four meals makes it more personal. He could easily have written a book about food supply chains in the United States without including his own prepared meals. Pollan’s gamble that such an approach would better reach his audience was most likely part of the reason for the book’s success. He established a connection with his audience early and then sustained that by telling an engaging story at the same time that he made a compelling argument. In a sense, he invited the reader to sit down with him to dinner and have a conversation about food.

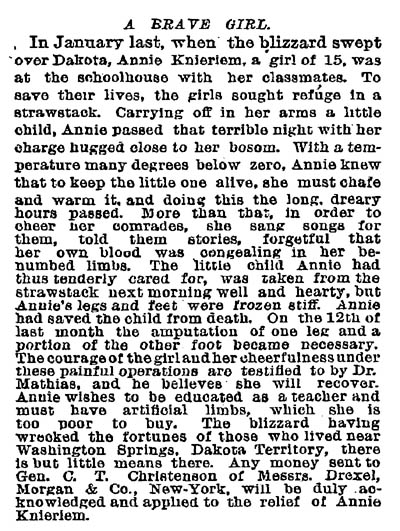

Consider the following excerpt from the introduction to David Laskin’s book, The Children’s Blizzard:

The blizzard of January 12, 1888, known as “the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard” because so many of the victims were children caught out on their way home from school, became a marker in the lives of the settlers, the watershed event that separated before and after. The number of deaths—estimated at between 250 and 500—was small….[but] it was traumatic enough that it left an indelible bruise on the consciousness of the region. The pioneers were by and large a taciturn lot, reserved and sober Germans and Scandinavians who rarely put their thoughts or feelings down on paper, and when they did avoided hyperbole at all costs. Yet their accounts of the blizzard of 1888 are shot through with amazement, awe, disbelief. There are thousands of these eyewitness accounts of the storm….The blizzard literally froze a single day in time. It sent a clean, fine blade through the history of the prairie. It forced people to stop and look at their existences—the earth and sky they had staked their future on, the climate and environment they had brought their children to, the peculiar forces of nature and of nature’s God that determined whether they would live or die.

1888 New York Times

List three sign-posts Laskin has deployed in this paragraph.

Based on this paragraph, construct a possible outline for the rest of Laskin’s book that illustrates narrative arc and argument structure.

What kind of meta-narrative do you think Laskin’s argument falls under?

New York Times, “Books,” www.nytimes.com/pages/books/index.html, Accessed November 7, 2008.

Powell’s Books, “Review-a-Day,” www.powells.com/review/all.html, Accessed November 7, 2008.

Rampolla, Mary Lynn. A Pocket Guide to Writing in History. 4th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. 2004

Laskin, David. The Children’s Blizzard. New York: Harper Perennial. 2005.

Maher, Neil M. “Mark Fiege and Stephen Mihm On Bank Notes.” Environmental History, Vol. 13, No. 2, 351-359. 2008.

Nye, David. “Technology, Nature and American Origin Stories.” Environmental History, Vol. 8, No. 1, 8-24. 2003.

Price, Jennifer. Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. New York: Basic Books. 2001.

Zuczek, Richard. State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. 1996.

Page revision date: 23-Mar-2009