Learning to Do Historical Research: Sources

Prowling the Periodicals

Newspapers, Magazines, Journals

Steel Wagstaff

Michelle Niemann

Introduction

Now when you want the latest news, you can point your browser to www.nytimes.com and read articles that are only minutes old. However, before the development of the Internet, and especially before the advent of television and radio, printed newspapers were the best way to keep up with current events.

Because periodicals are such an important forum for information and debate, they make great primary documents for the environmental historian. You can learn a wide variety of facts about a particular time, place, and community from old newspapers, magazines, and journals. Periodicals report events, but even more importantly, they give you a window into how people understood those events at the time.

This section will give you tips on how to find and use periodicals as primary and secondary sources for your research.

Table of Contents

Periodicals report events—from daily news stories, for-sale notices, and reviews of new novels to the proceedings of an academic conference—as or soon after they happen. “Periodical” is a general term for any newspaper, magazine, or journal that is published at regular intervals—once a day, once a week, once a month, once a quarter, or even once a year.

Whether the periodical in question is a newspaper aimed to keep the inhabitants of a city informed about current events or an academic journal designed to keep professionals in a discipline up-to-date on research in the field, periodicals speak to particular audiences at a specific moment in time. Though their news does not stay new for long, their lasting value to historians is in the thorough, idiosyncratic way they give a picture of a particular moment.

On this page, we will use the University of Wisconsin Libraries for our examples of how to search for periodicals. Though there are differences among libraries, the principles illustrated here apply to most university and public library systems.

Periodicals as primary sources

Periodicals are a great place to find the first published accounts of historical events. Say, for example, that you wanted to research the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 from the perspective of environmental history. You could begin by searching for Chicago newspapers published during the fire itself, from October 8 to October 11, 1871.

A few nineteenth-century periodicals are available through online databases to which your library may subscribe. In ProQuest Historical Newspapers, for example, you could find the Chicago Tribune of October 8, 1871, and read the front-page article, “The Fire Fiend. – A Terribly Destructive Conflagration Last Night.”

By searching your library’s catalog, you could find copies of other Chicago newspapers that are not available online. In the Wisconsin Historical Society Library, for example, the Chicago Evening Post from 1871 is available on microfilm, while the Chicago Times is available on paper in a bound volume.

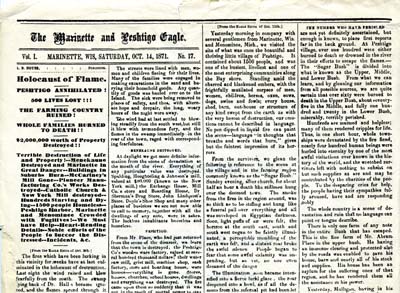

The Great Chicago Fire was just one of many fires across the Great Lakes states in 1871. In fact, the 1871 Peshtigo fire in Wisconsin killed more people and destroyed a much larger area than the Chicago fire. By searching in the University of Wisconsin Libraries’ catalog, you can find the first newspaper story of the Peshtigo fire, which is filed in the Historical Society Library’s Pamphlet Collection.

The Pamphlet Collection is in the Historical Society Library’s closed stacks, which are not open to the public. To see this newspaper article, you must request it from the librarian. What the librarian brings back from the closed stacks is a file folder with the October 14, 1871, copy of the Peshtigo Eagle, a single-sheet newspaper:

(click for larger version)

Image: Peshtigo Eagle Front Page, October 14, 1871

Periodicals like this not only give detailed accounts of the facts—who was killed, whose property was destroyed, how farmers and townspeople reacted to the fire—but also let you know how some people close to the event interpreted it.

Return to Top of Page

Periodicals as secondary sources

Periodicals might be the first documents that come to mind when you think of secondary sources. Academic journals, which publish articles by scholars in a given discipline, are often the best way to learn about the latest research, especially in the sciences and social sciences.

Most academic journals publish new issues two, three, or four times a year. University libraries usually subscribe to many academic journals, and you can find their most recent issues in your library’s current periodicals reading room.

Gated, online databases provide the best way to search for scholarly articles on specific topics. Libraries subscribe to these databases, which store articles from thousands of different periodicals behind a virtual “gate.” In other words, you cannot find these articles through a Google search on the free, public Web.

You could begin by searching an online database for articles on the Great Chicago Fire from history journals. For example, by searching JSTOR, an article database, you could find John J. Pauly’s article, “The Great Chicago Fire as a National Event,” published in American Quarterly in 1984.

If you wanted to learn how ecologists understand forest fires, you could search for scientific articles on the subject in databases like JSTOR, Web of Knowledge, or Environmental Sciences and Pollution Management.

Remember, your research question determines how you use a source.

If you were researching the 1871 fires in the Great Lakes region, you would use newspaper accounts published at the time as primary sources. Recent articles about the 1871 fires in academic journals would serve as secondary sources.

If, instead, you were researching the history of fire management practices, scholarly articles on how people should respond to wildfires would be your primary sources. You could search for these articles in academic journals on forestry or environmental science published during the period you are studying.

Return to Top of Page

Because periodicals are now available in many formats, there are many ways to find them. If you are unsure about how to find a particular journal or magazine, ask a librarian for help.

To find the most recent issue of a newspaper, magazine, or journal, begin on the Web or in your library’s current periodicals reading room. While many newspapers now make the latest news available on the public Web for free, some specialized journals do not put any of their content online.

Many old newspapers, magazines, and journals can only be found in the library, where they are kept on microfilm or in bound volumes. However, past issues of some journals are available on the public Web or through gated, online databases.

Gated Web

Full-text versions of many academic journals as well as some newspapers and magazines are available on databases to which libraries can subscribe. Because the materials they contain are under copyright, these databases are “gated”—that is, you cannot access the articles they contain on the free, public Web.

Most libraries subscribe to some online databases, and university libraries often subscribe to many of them. Subscriptions to these databases are expensive and give you access to a wealth of sources that are not available on the public Web.

You can use these databases—sometimes called a library’s electronic resources—from any computer in the library. If you are a college student or have a public library card, you can sign in to the library’s website, using your student ID or library card number, to access the library’s databases from elsewhere.

Often, a library’s website allows you to search multiple databases in a given subject area at once or to access a single database and search it alone. Here are a few of the major databases that provide access to periodical articles:

- JSTOR

- ProQuest Newspapers

- Academic Search

- Web of Knowledge (Web of Science)

Public Web

Some libraries and other organizations have digitized their paper archives, including periodicals, and made them available for free on the public Web.

For example, the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections have made the library’s archives of some specialized periodicals, such as The United States Miller, a nineteenth-century trade publication from Milwaukee, available online. Here’s a link to their website: http://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/index.shtml

(click for larger version)

Source: The United States Miller. Volume 7. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: No. 1, 1879.

http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/WI.USMillv07

Microfilm and microfiche

Many periodicals, especially ones that were printed on paper that disintegrates quickly because it is acidic, were photographed and stored on microfilm or microfiche. You can find these through your library’s catalog.

Microfilm and microfiche are often kept in drawers labeled with call numbers. Sometimes you must ask a librarian to retrieve them for you from an area closed to library visitors.

Microfilm is a spool of film on which pages of text are stored in miniature form. To read microfilm, you thread the film into a microfilm reader in the library, which magnifies the images so that you can read them on a screen. Usually, you can pay to print individual pages.

Microfiche works on the same principle as microfilm, except the pages of text are kept on individual slides (“fiche”) instead of spools of film. To read microfiche, you use a microfiche reader in the library, which makes the text legible on a screen. You can also pay to print pages from microfiche.

Bound periodicals

Paper copies of some periodicals are kept in bound volumes in the library. These bound volumes are usually labeled with title, date, and volume numbers. Before the advent of microfilm and, later, the Internet, libraries bound the paper copies of periodicals to which they subscribed and shelved the bound volumes in the stacks.

For example, libraries usually bound quarterly academic journals in volumes that contain the four issues from a given year. In some cases, you can check these bound volumes out, but in others you must use them in the library.

Special collections or archives

Some periodicals are stored in a library’s special collections or archives. Usually these paper copies are non-circulating—that is, you must use them in the library instead of checking them out. The Wisconsin Historical Society Library’s Pamphlet Collection, mentioned above, is an example of an archival collection that includes some periodicals.

Searching the library catalog for periodicals

To find periodicals in the library—whether on microfilm, in bound volumes, or in special collections—you must use the library’s catalog.

If you know the title of the newspaper, magazine, or journal you need, try searching the library catalog by “journal title” or “periodical title” (rather than by “title” or “keyword”).

If you want to find all the periodicals from a specific city or town, search for the place’s name as a “subject heading” in the library’s catalog. Scan the subject headings that result for subdivisions such as “—Periodicals” or “—Newspapers.”

For example, in the University of Wisconsin Libraries catalog, a search for “Peshtigo” in “subject heading browse” leads to “Peshtigo (Wis.)—Newspapers,” a subject heading that includes seven newspapers from Peshtigo.

The H.W. Wilson Company also publishes a very useful reference work called The Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature that can help you find useful periodical titles within your discipline.

Return to Top of Page

Periodicals can contain almost anything. Be prepared to be really surprised when you start looking at old periodical sources. For example, in one issue of the United States Miller, the following were things listed under the heading NEWS OF THE WORLD: “March 1st, 1879, there were 47,009 post offices in the United States; An attempt was made to assassinate the Czar of Russia, April 14th; A pound of oat meal is said to possess as much nutriment as 9 pounds of ham; Nearly eleven million dollars worth of flour were shipped to South America last year;” and the joke: “There is only one miller in Congress. No wonder the old thing grinds slow.”

When reading periodicals, remember . . .

- Periodicals often contain the earliest written records of important events. They may be as close as you can get in time to the event you are studying.

- Many periodical sources are written for regional or niche audiences. Periodicals are especially good at recording important local information, including details you will not find in national news sources. For example, the local newspapers published after the Peshtigo fire included stories of personal artifacts (watches, knives, and other belongings) discovered in the fire’s wreckage.

- Many periodicals include a lot of things that are not preserved anywhere else. Some of these things weren’t considered worthy of being recorded in a more lasting format at the time, but may be useful to you as a researcher.

- Periodical sources can contain mistakes. Standards of journalism have changed over time, and not all stories are thoroughly fact-checked. Remember that periodical sources are not necessarily one-hundred percent reliable.

- Be cautious: not all periodicals are written purely to inform or report the facts. Many other motives shape the way that writers tell stories in periodicals as in other sources.

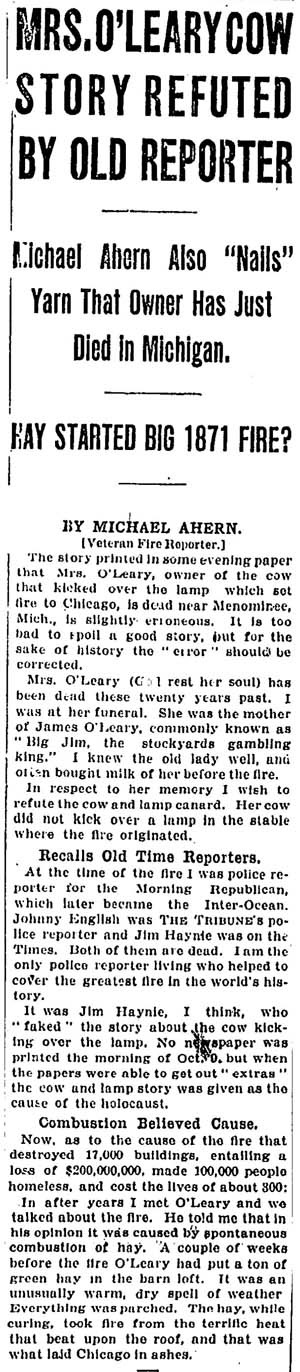

What you can learn from periodicals: The Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 is often blamed on Mrs. O’Leary’s cow. The story of a cow kicking over a lantern and setting the city on fire has become a legend as well as the punch line for countless jokes. With a little searching, we discovered that this story came from the first Chicago newspaper article to explain the start of the fire, “The Great Calamity of the Age!,” in the Chicago Evening Journal Extra of October 9, 1871.

At first, we were really excited to have discovered the mythic story in a print source so close to the actual event. Later, however, we came across a 1915 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune titled “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow Story Refuted by Old Reporter.” In this article, a Chicago reporter named Michael Ahern claimed that a man named Jim Haynie had invented the story.

Shortly after, we found another newspaper article, this time from 1921, in which Michael Ahern claimed he himself was the reporter who invented the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicking over the lamp (“1871 Reporter Writes Story of Great Fire,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, 9 October 1921, sec. 1, pp. 1,3).

(click items above—left column and text to its right—for larger versions)

At that point we felt unsure about almost everything. Had the Mrs. O’Leary story been invented by a reporter? If so, why had Ahern waited until so much later to confess? And which of his confessions was true?

As we continued our research we found (you guessed it!) another helpful periodical source. This one was a scholarly article by Richard Bales, published in the Illinois Historical Journal in 1997. In this article, which later became a book, The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, Bales uses evidence from hundreds of periodicals to argue that neither of the Ahern confessions are accurate.

Using an issue of the Chicago Daily Journal printed on the fiftieth anniversary of the fire along with published remembrances of it, Bales argues that local children told the reporter assigned to cover the fire (who, by the way, was not Michael Ahern) that the fire had been started by a cow kicking over a lamp.

Phew. Exhausted? We were. So, what can this story teach you about how to use periodicals? Here are some ideas:

- Be cautious about how much you trust any single periodical source, even if it is very near in time and space to the events it describes.

- Do not stop searching when you have found one source. Compare what you have found in one source to what appears in other sources. Do not make a claim based on any single source without finding support for it elsewhere.

- Not all of your sources will agree with all of your other sources. This is frustrating, but it can make your search more exciting.

- When sources disagree, you will have to make some judgments in deciding whom you will believe and why, and then justify these decisions in making your argument.

- Even if a source is not true, it might still be useful. Even though we cannot verify the popular story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, it can still teach us something about history. Since newspaper stories at the time portrayed Mrs. O’Leary as a stereotypical Irish immigrant, you might choose to explain the story’s popularity by connecting it to anti-Irish, anti-Catholic sentiment and anxiety about immigrants. Or you could argue that it is an example of the public’s need to find a scapegoat (or in this case, a scapecow) to explain why bad things happen.

Return to Top of Page

How to make an argument based on periodicals

When you use a periodical to make an argument, be sure to question your sources as described in the previous section.

Use periodicals as a source of information

Historians use periodicals as a source of facts, from descriptions of newsworthy events to notices of sale and or of birth, marriage, and death. The newspaper articles about the Chicago and Peshtigo fires cited above are examples of periodical sources that could be used this way—with the warning that you should never rely on a single article in isolation.

Use periodicals to show how people understood events

Though obtaining a wide variety of factual information is the most obvious use historians might make of periodicals, it is not the only one. Historians can also use periodical articles to show how people at the time interpreted the environmental causes and consequences of events.

In Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire, Stephen J. Pyne uses periodicals this way. From nineteenth-century newspapers and trade journals, Pyne learned how Americans understood wildfires.

While environmentalists today would probably blame the forest fires on the logging that left large amounts of fuel, or “slash,” on the ground, some people at the time thought that loggers—and even the fires themselves—prepared the ground for farmers. In fact, Pyne found issues of the Lumberman’s Gazette in which writers argued that the forests near the Great Lakes should be logged even more quickly to save the valuable timber from forest fires.

Pyne writes, “In the midst of chronicling the devastating 1881 fires, the Detroit Post paused to observe without irony that here was a real ‘chance for new settlers . . . where the fires have raged the forests have been killed, the underbrush burned and the ground pretty effectively cleared.’”

Return to Top of Page

You can find almost anything in periodicals. Periodicals offer a breadth of materials unmatched by almost any other kind of source. Here are the kinds of things in periodicals that might be useful for your research in environmental history:

- News or reportage tries to present a balanced, objective account of something notable that has happened recently somewhere in the world. Description of events will sometimes be accompanied by brief efforts to interpret or explain.

- In opinion, commentary, or editorials, authors try to persuade their readers to agree with their viewpoint or to take some kind of action. The Federalist Papers, originally published in two New York newspapers, are a particularly good example. In some older newspapers, it might be difficult to tell the difference between commentary and news.

Periodicals are also great sources for financial news, since periodicals’ frequent publication allows them to provide the speedy and reliable information that is valuable in a marketplace. Some periodicals are devoted entirely to providing financial news, some contain separate business or financial news sections, and others simply note major events or trends in large markets (like changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average or reports from the New York Stock Exchange).

- Periodicals often feature legal or commercial notices. These can record major property transactions, notices of upcoming sales, or announcements for public hearings, government meetings, or community-based civic events.

- Advertisements give periodicals another stream of revenue in addition to subscriptions. If you are curious about the history of marketing, periodicals are full of very useful sources.

- Some periodicals are entirely devoted to satire—writing that makes fun of some aspect of contemporary society—while other periodicals contain a humor section.

- Obituaries, marriage and birth notices, and social records often provide more details about these events that you can find in the basic legal records. Some periodicals have “society” pages that contain juicy gossip about local families and even report on big parties or celebrations. If you were writing about the environmental impact of exotic fashion in the 1920s, you might turn to a description of a fashionable party from that period for an anecdote that could help bring your data to life.

- Some periodicals also contain literature. Many famous novels from the nineteenth century were originally published serially, chapter by chapter, in periodical sources. In some cases, you may find that the serialized versions differ from the published novels. If you wanted to find out about the development of Charles Dickens’ views on urban pollution in London, for example, you could look at the periodicals where some of his novels first appeared.

- Periodicals also contain specialized content depending on their audience. You can find periodical sources written for almost any interest group. For environmental history research, newsletters for industry or advocacy groups can be valuable. Think about what you could learn from Sierra Club newsletters or old issues of Earth First!.

- Periodicals are also where you can find some of your best secondary sources, particularly scholarly articles written by previous researchers examining questions related to your own. In every field there are leading academic journals; ask a professor or librarian about the most influential periodicals in your field. Environmental historians should be familiar with Environmental History, American Historical Review, Journal of American History, and Isis.

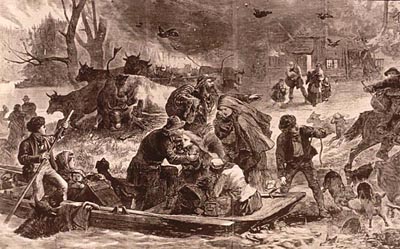

- The images, drawings, and photographs in periodicals are visual records of events created at the time they happened. Some of the most famous images from the 1871 Chicago fire were drawings that appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. The same is true of the fire that burned around Peshtigo, Wisconsin at roughly the same time. Below is an artist’s imaginative rendition of the scene at Peshtigo as it appeared in the November 25, 1871 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

Source: Pernin, Peter. The Great Peshtigo fire: An Eyewitness Account. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971. From the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Pam 78-4295 http://www.library.wisc.edu/etext/WIReader/Images/WER2002-07.html

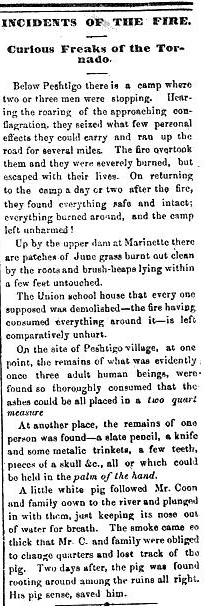

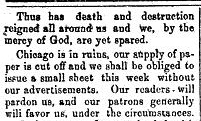

As an example of the variety you can find in periodical sources, we have posted a couple of pages from the Menominee and Peshtigo Eagle, the Wisconsin newspaper that served the region most affected by the 1871 Peshtigo fire. The first two images come from the first issue published after the fire reached Peshtigo:

(click for larger version)

(click for larger version)

Source: The First Newspaper Story of the Great Peshtigo Fire, October 8, 1871. Peshtigo, Wis.: The Peshtigo Times, [1951]

From the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Pam 57-1251.

www.library.wisc.edu/etext/WIReader/WER2001c.html

Looking back at the pages just shown, you can see that most of what appears is a report of the fires, though this report is probably very different from the news reports you are used to reading. For example, look closely at the section that appears at the top right of the second page entitled “Incidents of the Fire.”

The last paragraph tells the story of a few places that managed to survive the fire unscathed, the macabre details of how little the fire left of its victims, and a curious story of a pig that lived through the fire by virtue of its “pig sense.”

Another notable thing about the pages just shown is their lack of advertisements. At the top left of the second page you can find an explanation for this.

Even though the paper is lacking advertisements, that doesn’t mean that it only contains reports related to the fire. If you look closely at the second page you can see that the paper also includes a notice about the Marinette Post Office hours, information about a local social organization, a Marinette church directory, and publicity for a political meeting.

The point here is that if you can find so much unique material in a periodical published in a community just after a catastrophic event, you can find it in almost any periodical.

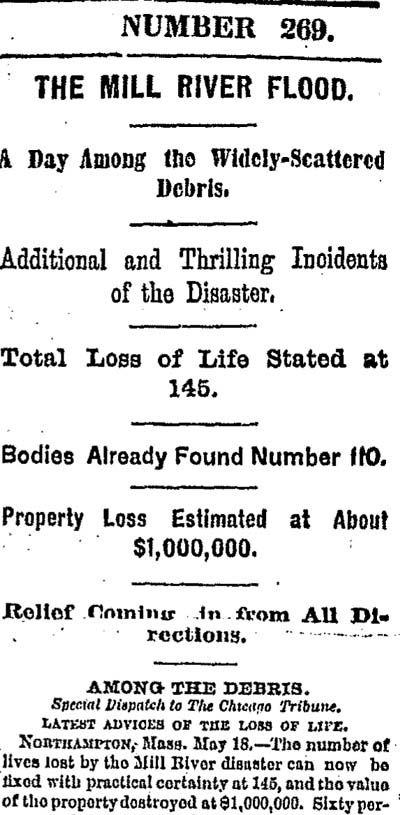

Here’s another example of the diversity of materials you can expect to find even on a single page of a newspaper. It’s the front page from the Chicago Daily Tribune on May 19th, 1874, chosen for its report of a deadly flood in Massachusetts (which could be really useful if you were researching the social and environmental impact of water-powered New England mills):

(click for larger version, or read on; large file will be slow to download; zoom your browser to read)

Starting from left to right, notice the following things: two columns of advertisements...

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

a section called “Notes and News” that features a brief description of a Congressman’s wedding...

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

the Congressional Record section (reports on recent happenings in Congress)...

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

a Wall Street section with some financial news; an announcement for a Prohibition conference to be held in Indiana; a brief obituary; a short announcement predicting crop prospects...

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

and finally, in the last column, an account of the deadly Mill River flood in Massachusetts:

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

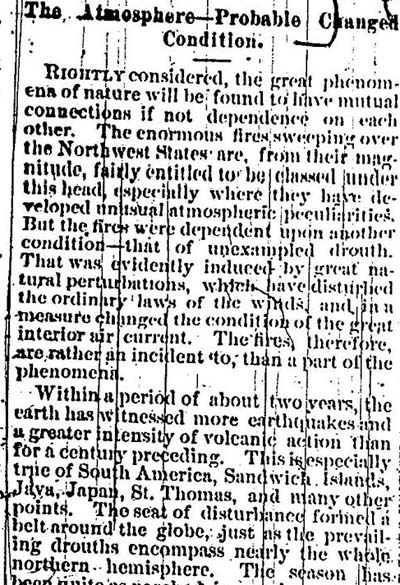

And that’s just the first page. So, how can all this variety help you in your environmental history research? Because such variety is common in old newspapers, you’ll occasionally stumble onto some really incredible finds. For example, while browsing through the issues of the Peshtigo and Menominee Eagle published after the fire, we found the following article:

(click for full text of column; zoom your browser to read)

If you look closely at the image above, you’ll find that it gives one contemporary explanation for the fire. In trying to explain the fire, the author of the article describes recent environmental changes and interprets the origins of the fire according to the science of the time, making it an invaluable primary document for someone who wants to understand how contemporaries explained the causes of the great fires of 1871.

Return to Top of Page

- Do remember that not all periodicals are on the Web.

- Do use periodicals available only in the library’s microfilm, bound volumes, and special collections.

- Do try more than one method of searching for periodical articles.

- Do search for more than one periodical source on a given event.

- Do compare periodical sources to get the full story.

- Do browse through old newspapers and magazines for interesting items beyond the article you were searching for.

- Don’t trust every report that seems like news.

- Don’t forget to think about how a periodical’s audience affects the stories it contains.

Interesting Links

American Antiquarian Society. “Archive of Americana.” http://www.americanantiquarian.org/digital2.htm#news

Cornell University Library. “Finding Periodicals and Periodical Articles.” http://www.library.cornell.edu/olinuris/ref/research/periodical.html

The Library of Congress. “Chronicling America: Historical Newspapers.” http://www.loc.gov/chroniclingamerica/index.html

The Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature. Minneapolis: H. W. Wilson, 1901—present.

Research Society for American Periodicals. “Resources for Research: Periodicals.” http://home.earthlink.net/%7Eellengarvey/rsapresource1.html

Smithsonian Institution Libraries. “Online Electronic Journals from Smithsonian Libraries" http://www.sil.si.edu/eresources/tfr_ej_vendorresults.cfm?vendor=ProQuest%20Historical%20Newspapers

University of Michigan. “Making of America: Journals.” http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moajrnl/

University of Wisconsin. “University of Wisconsin Digital Collections.” http://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/index.shtml

Return to Top of Page

Ahern, Michael. “1871 Reporter Writes Story of Great Fire.” Chicago Sunday Tribune, October 9, 1921, sec. 1, pp. 1,3.

Ahern, Michael. “Mrs. O’Leary Cow Story Refuted by Old Reporter.” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 21, 1915, sec. 2, p. 13.

Bales, Richard F. The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2002.

“The Fire Fiend. – A Terribly Destructive Conflagration Last Night.” Chicago Tribune. October 8, 1871, sec. 1, p. 1.

The First Newspaper Story of the Great Peshtigo Fire, October 8, 1871. Peshtigo, WI: The Peshtigo Times, [1951] From the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Pam 57-1251.

“The Great Calamity of the Age!” Chicago Evening Journal Extra, October 9, 1871.

“Holocaust of Flame.: Peshtigo Annihilated!” The Marinette and Peshtigo Eagle, Vol. 1, No. 17, Oct 14, 1871.

Pauly, John J. “The Great Chicago Fire as a National Event.” American Quarterly 36.5 (Winter 1984): 668-683. JSTOR.

Pernin, Peter. The Great Peshtigo fire: An Eyewitness Account. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971. From the State Historical Society of Wisconsin: Pam 78-4295.

Pyne, Stephen J. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

The United States Miller. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1879, Vol. 7, No. 1. Image ID: WI.USMillv07, University of Wisconsin Digital Collections.

Return to Top of Page

|