|

|

|

||||

Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer

|

Library of Congress Classification System |

Call Number |

Subject |

A |

General Works |

B |

Philosophy, Psychology, Religion |

C |

Auxiliary Sciences of History |

D |

World History and History of Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, etc. |

E |

History of the Americas (United States) |

F |

History of the Americas (United States local history, British America, Canada, Dutch America, French America, Latin America, Spanish America) |

G |

Geography, Anthropology, Recreation |

H |

Social Sciences |

J |

Political Science |

K |

Law |

L |

Education |

M |

Music and Books on Music |

N |

Fine Arts |

P |

Language and Literature |

Q |

Science |

R |

Medicine |

S |

Agriculture |

T |

Technology |

U |

Military Science |

V |

Naval Science |

Z |

Bibliography, Library Science, Information Resources |

Books relevant to the topic of wolves in Yellowstone National Park, for example, are shelved under Q (Science) as well as E (United States history) and F (United States local history). In a large university library system, the books in these call number ranges may be located in completely different libraries across campus from each other.

Until the advent of computers, every library kept its catalog on alphabetized paper cards. It is much easier to find books through today’s digitized catalogs than through the old paper card catalogs, but online library catalogs require different search methods than Google or Amazon.

While Google and Amazon allow for “fuzzy” searches—i.e., if you spell something wrong or include unnecessary words, the search engine can still guess what you want—online library catalogs cannot retrieve the records for relevant books if you spell a word incorrectly or include search terms that are not in the catalog record.

Back in the days of paper cards, each library had three sets of catalog drawers: an author catalog, a title catalog, and a subject catalog. For each book, there would be one card in the author catalog, one in the title catalog, and two or three in the subject catalog. While librarians have moved catalog records from paper cards to online databases, these three categories—author, title, and subject—continue to be the most important and reliable ways to find books through the catalog.

Here are some tips on the most efficient ways to search the library’s catalog:

[click to view larger image]

Adapted from Bowdoin College Library’s website

Subject headings have been a part of a library’s way of organizing knowledge since the days when a library’s catalog was kept on paper cards. Both the Library of Congress and the Dewey Decimal Classification Systems still tag each book, periodical, or other source with subject headings. These subject headings appear as clickable links in the online catalog’s record. Take this entry from the University of Wisconsin Libraries’ MadCat catalog:

Author: Sellars, Richard West, 1935-

Title: Preserving Nature in the national parks: a history / Richard West Sellars.

Publisher: New Haven [Conn.]: Yale University Press, c1997.

Description: xiv, 380 p., [16] p. of plates : ill. ; 25 cm.

Notes: Includes bibliographic references (p. 293-360) and index.

ISBN: 0300069316 (alk. paper)

OCLC: (OcoLC)36800594

Subjects: United States. National Park Service—History.

National parks and reserves—United States—Management—History.

Nature conservation—United States—History.

Natural resources—United States—Management—History.

All of the underlined phrases in this record are clickable links. If you click on one of the subject headings, the online catalog takes you to an alphabetized list of subject headings that looks like this:

# Titles Headings

1 National parks and reserves—United States—Management—History.

3 National parks and reserves—United States—Management—Periodicals.

16 National parks and reserves—United States—Maps.

1 National parks and reserves—United States—Maps—History.

The numbers to the left of each subject heading indicate the number of titles tagged with that heading. If you click on “National parks and reserves—United States—Maps,” the catalog will take you to a list of the sixteen sources that share that subject heading.

National parks and reserves—Law and legislation—Wyoming.

National parks and reserves—United States—History.

National parks and reserves—Yellowstone National Park—Management.

Shelving books by subject is the library’s oldest way of organizing knowledge. Here are some tips on how to use the library’s method of shelving to help you find great sources:

Location: Historical Society Library Stacks

Catalog: UW Madison

Call Number: SB482 A4 S44 1997

Status: Not Checked Out.

This is the most effective—and efficient—research technique. If you use the first sources you find to uncover other sources, you will write a much stronger paper than you will if you find all of your sources through keyword searches.

Why? Because tracking down the books and articles that your sources cite will propel you into the middle of a conversation about your topic. As you come to understand how various writers have interpreted your topic—how they respond to, revise, or disagree with each other—you will figure out exactly what you want to contribute.

Here are some tips on using the books you find to uncover the best sources on your topic:

For example, in his introduction to Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, Mark David Spence argues that forcing American Indians out of areas they occupied was a key component in the founding of national parks in the American West.

Spence writes, “scholars and park officials have long asserted that native peoples avoided national park areas because these places were not conducive to use or occupation.9 Yet nothing could be further from the truth . . . native peoples made extensive use of these areas – often well into the twentieth century.”

If you look up footnote number 9, you find that Spence cites a scholar who advocates the position he refutes: “See, for example, Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience, 3rd ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 53.” To assess that scholar’s argument, you can look up his book.

Though you should never rely on or cite overview sources such as textbooks or encyclopedias in a research paper, encyclopedias are a great place to begin narrowing your topic and finding books. The most familiar encyclopedias—Encyclopedia Britannica, World Book, and Wikipedia—are general encyclopedias. Specialized encyclopedias are devoted to particular subjects or disciplines, such as economics, art, or history. Because they address a narrower range of topics, specialized encyclopedias can give more in-depth overviews of them.

General encyclopedias and some specialized encyclopedias are available through your library’s gated Web, but many specialized encyclopedias are available only in print. Encyclopedias are often shelved in a reference room separate from the regular stacks.

Articles from academic journals make great sources for papers. Finding journal articles is quite different from using the library or searching the public Web, so we will try to give you a few important links and tools to use to find the right journal articles for your paper. We will also give you a few tools to get the information that you need out of a scientific journal article.

Academic journals contain the most up-to-date knowledge for the different disciplines. Most top research institutions in the US grant tenure to faculty based on their ability to publish research, and for many disciplines, especially the sciences, this mostly means to publish articles in academic journals, so the importance of these journals cannot be overemphasized.

Think of journals not only as sources of information, but as the venues for scholars to hold discussions about the topics that they are passionate about. This conversational aspect means that journals publish that which is at the forefront of its particular discipline. Most of these journals are “peer-reviewed,” which means that each article submitted by a researcher is reviewed by a few scholars who are considered to be the leaders in the field that the article falls under. If the reviewers decide that there are any problems with the methods, writing, or analysis, or that the article does not contribute anything new or significant, then the journal will not publish the article.

Articles in science journals offer new empirical data and theories, mostly from field or laboratory work. Disciplines in the natural and social sciences, such as biology, physics, sociology, chemistry, climatology, psychology, anthropology, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, economics, and business, often use journals as their main mediums for publishing new theories and original research. Scientists still occasionally write books, but their articles make up the foundation of their reputation, and the more the article is cited, the more prestigious it and its author become.

While peer-reviewed journals also play an important role in the arts and humanities, historians still publish their new findings and analyses in single-author books rather than academic journals. BUT art and humanities academic search engines are often the best places to search for reviews of books and other works, as well as a huge variety of other things like images, art periodicals, reviews of musical performances, poetry, obituaries, philosophical discussions – so many things!

For the purposes of this page, we will just focus on some general searches, but if you would like to see the wide range of information available, you can visit University of Nebraska’s index of arts and humanities journal articles (http://www.unl.edu/libr/indx/artshum.html) or our page on scientific and other quantitative data.

As a public Web search begins with Google, so a journal article search begins with an academic journal search database. There are many different databases and search engines, and most are “gated”—that is, not accessible through the public Web without a subscription. Most libraries pay to subscribe to a variety of these databases. You can access those that your library subscribes to through your library’s website. Usually, you will have to use an ID number to log in or search on a computer in the library. You should first check your university’s or library’s website to see which ones you have access to.

Which search engine you use will depend on what field you are searching in. Since these often change, it is best to ask a librarian or professor which search engines they would use for your particular topic and field.

However, here are some search engines that are always a good start:

If you do not have access to subscription-based journals, here are some free alternatives:

Let’s start with our topic of wolves in Yellowstone. You go to your university’s library system homepage, log in, and navigate to the journal search page, which should say something to the effect of “journal,” “database,” or “e-resource” search. When you arrive at this page, the library will ask you to log in with the student ID and password. Once you log in, you now have access to all these resources; consider yourself lucky!

Find the JSTOR link on the library page, click it, and it will take you to the JSTOR homepage. Since you navigated there from your library’s website, you will be able to use the JSTOR database. If you just type in www.jstor.org and try to search, you will not be granted access.

The first search page opens and gives you a chance to type in a box for a keyword search. For these search engines it is best to always use the advanced search.

For the initial search try to find articles about wolves in Yellowstone, but knowing that there are probably a billion articles that mention Yellowstone and wolves, you can refine your search to just look for those words in the title, which should only find articles that are mainly about wolves in Yellowstone:

Notice that we changed the boxes on the right from “full-text,” which would just be a keyword search throughout all the documents, to “article title.” Also notice that instead of putting down “wolf” or “wolves,” we have written “wolf#.” The reason for this is that in JSTOR, placing “#” after a word will search for all the words with the same stem, so it will search for “wolf” and “wolves.” If we put “goose#,” it would search for “goose,” “geese,” and even “gosling.” These search options have advantages over simple Web searches, and each database search engine uses a different system, so for examples of these ways to use detailed searches, go to the search engine’s help page and find the page for tips on searching – they are usually easy to understand.

You also want to limit the types of journal articles that will come up. To see how we did that, look further down the page:

Depending on how detailed you would like to get, you could be very specific in the types of articles that you are looking for. Are you just looking for articles about wolf population biology and the current state of their populations? If so, you could just select to look in “Ecology & Evolutionary Biology” journals, and you would not have to wade through many things. At this stage, however, maybe you are interested in the wolves’ interactions with American Indians, where wolves show up in art, or what business is being affected by their populations. So check those ones that you think might be interesting and click “Search.”

With that simple search and the narrowing down, you get back 19 results. This is great! This gives you a broad range without overwhelming you with information.

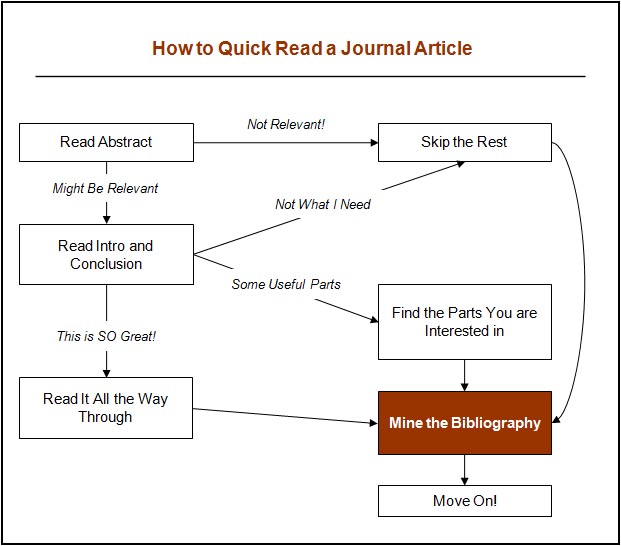

The following techniques are useful for obtaining information from a journal article in the sciences and social sciences, because they are written quite distinctly from other bodies of literature. They do not apply to journal articles in the humanities, which are not organized as uniformly.

Don’t read that article all the way through. The first of the tricks is NOT to see a scientific article like a novel, which should be read cover-to-cover; you should see the article as a source for bits of information and wisdom that you can extract. Journal articles in the sciences are designed to deliver information as concisely as possible. While this style often makes articles difficult to read, it also makes them easy to mine for information.

Even though section names may vary among journals, articles in the natural and social sciences are most often organized into the following template:

With this template in mind, read the abstract, ask yourself what information could be contained in this article that could help in your project, and search out that information very deliberately. We are not suggesting that you should not read any articles all the way through. You may be interested in the entire picture that the author paints in the article, or it may relate directly to what you are studying. You should read some articles all the way through, while you should focus on particular sections or information in others. Most importantly, be deliberate in your reading process.

After much debate has taken place in a field, someone will usually write a review article that covers the most important movements and literature in that particular field. If you are starting to investigate a topic, and you are going to consult scientific literature, always look for review articles first. If there are any about your topic, they will tell you so much of what you need to know, AND they will point you towards the most important sources.

If you search for articles about wolves in Yellowstone, you might find a book review of Wolf Wars: The Remarkable Inside Story of the Restoration of Wolves to Yellowstone in the journal Conservation Biology:

This article tells you, first, that this book exists, and that it is important enough to be reviewed in Conservation Biology, which is a highly respected journal in the field. After a short read or scan, you also learn more about what the book has to offer, which is a history of wolf extirpation (local extinction) in Yellowstone, the changing of popular opinion from hatred to glorification of the wolf, and the long battle to reintroduce populations to Yellowstone. What a great find! Now you can go get this book out of the library.

Another interesting article is towards the bottom of the results:

If you are interested in social impacts of the wolf’s reintroduction, this is a great article, and since it is relatively recent, you can also expect that it will have a long list of useful sources

Among the over 70 sources, two of them stick out as being particularly interesting:

The Mech article is found in the book Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation, which seems to be a compilation of articles from different authors, since it is edited. That book would be perfect background for your paper.

You also find this article from the US Fish and Wildlife Service:

This article cites a final environmental impact statement that will likely chronicle the wolf reintroduction and its projected effects. If your paper is about these impacts, this document or a more recent environmental impact statement would be invaluable.

Now that we know how to start a search and get good direction for the background sources of out paper, it will help if we review some principles and tips for finding the best articles and authors for our papers.

You should use journal search engines in much the same way you use online library catalogs, but there are a few key differences:

The most important thing to remember when searching the public Web is that anyone has the ability to post information on the Internet without any approval or oversight. Material on the Internet can appear in the form of fact, story, opinion or interpretation, and may have been created to inform, sell, persuade, or change a belief.

Therefore, it is essential for you to verify the credentials of the author or organization, as material on the public Web varies greatly in its accuracy, reliability and overall value.

Let’s continue with our search example of Yellowstone National Park. Wanting to take advantage of resources on the public Web, you type “Yellowstone” into a Google search, and your simple search retrieves just below 10 million results! However, upon first glance of your results you notice many advertisements for lodges near Yellowstone. Besides links to the National Park Service website and Wikipedia, all of the first ten hits are promoting vacation ideas and accommodations in the park.

As an historian—and, generally, a student in academia—it is important to know that you must not ever cite Wikipedia as a source; however it is a good website to gain a quick introduction to a topic and possibly find interesting sources. Since probably none of the websites promoting vacations in your Google search will be of use to you, your best bet may be the National Park Service website.

While the National Park Service website may not be the flashiest website on the Internet, its main objective—like most “.gov” websites—is to provide interested visitors with useful information. Websites that are operated by government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and reputable news sources are often reasonably trustworthy—though of course they too have points of view and biases that you'll want to analyze.

For historical background, you will likely find that the “History & Culture” tab on the sidebar of the Yellowstone National Park website will provide you basic information about the history of the park.

While the Yellowstone National Park website will be the most reliable for your research, do not automatically discredit the other websites or base all of your research solely on the National Park site. However, since you will not have enough time to evaluate all 9,400,000 results on Yellowstone, be sure to further narrow down your search, weed out websites that will not help you, and use your discretion in evaluating the information on your chosen sites.

Primary documents are materials produced by actors in a specific time period; they provide the evidence that historians rely upon most. As a result of this, primary documents are the most important documents to look at when you are conducting historical research.

However, one of the most difficult aspects of researching primary documents is that they often are not organized as efficiently as books or journals. Therefore, primary document research requires a lot of time and patience. To learn more about primary documents, visit our pages on this website introducing different kinds of historical sources: Maps, Interviews, Government Documents, Images, Landscapes, Manuscripts, Periodicals, and Quantitative Data.

To help alleviate much of the work that goes into tracking down certain documents, there are primary document finding aids that are available on the public Web that can help point you to the primary document collections that will best serve your research needs.

A great example of a primary document finding aid accessible on the public Web is that of Yellowstone National Park. Starting at the Yellowstone home page (http://www.nps.gov/yell/), clicking on the “History & Culture” tab on the side bar will bring you to a section of the National Park’s website established for historical research. From here clicking on “Collections” and then “Archives” will bring you to Yellowstone National Park’s primary document collection guide.

[click to view larger image]

Yellowstone’s archive webpage will tell you everything you need to know about accessing the collection.

What the Yellowstone website doesn’t provide, however, are the documents housed in their archives. To see those documents, you will need to arrange a visit to the actual collection.

The College at Brockport, State University of New York. “Reading Academic Journal Articles.” http://www.brockport.edu/sociology/journal.html. 2008.

Mann, Thomas. The Oxford Guide to Library Research: How to Find Reliable Information Online and Offline. Third Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Spence, Mark David. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “Journal Article Indexes of Arts and Humanities.” http://www.unl.edu/libr/indx/artshum.html. 2006.

Page revision date: 23-Mar-2009