Lecture 2:

What Is Landscape and Why Should We Care About It?

Suggested Readings:

Curt Meine, "Reading the Landscape: Aldo Leopold and Wildlife Ecology 118," Forest History Today (Fall 1999), 35-42. http://curtmeine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/1999-Reading-the-Landscape.pdf

Look up the definition of "landscape" in the Oxford English Dictionary to trace the history of the word.

John Wylie, Landscape (2007).

Introduction:

This lecture pairs with last Wednesday's lecture as an introduction to the course. Last week's lecture was a "show me" lecture featuring Portage, Wisconsin and the Fox River: showing you how to take a place and rendering it meaningful using historical context, storytelling, and analysis. Those activities are very much what this course is about. Today's lecture is the "tell me" lecture, telling you what this course is about and what it aspires to teach you.

To begin, today's lecture will go through the syllabus. We recommend bookmarking the course website: http://www.williamcronon.net/courses/469/

On the course website you'll find the following resources:

- An HTML and PDF link to the course syllabus. (If we modify any items on the syllabus, this will happen in the HTML version. So check the HTML version for any modifications, rather than the PDF.)

- Copies of email announcements that were sent out to the class listserv.

- Notes from each lecture (posted under "Handouts").

- Information about the Place Paper assignment.

- Any other materials we decide to add as the semester progresses (e.g., copies of exemplary blue book essays for the midterm exam).

Within the syllabus you'll find the following information:

- Contact information for course staff. Email is the best way to reach Bill and TAs Rachel Boothby, Carly Griffith, and Rebecca Summer. If you set up a meeting time with BIll other than his usual office hours (9:45-11:45am Wednesdays in 5103 Humanities), he almost always holds such appointments in 443 Science Hall, NOT in the Humanities Building.

- A list of book-length course readings (three total). All non-book assignments—i.e. articles and PDFs—assigned for the course are available on electronic reserves accessed via the Assignments and Files tabs in Canvas (which is the main use we'll make of Canvas all semester).

- Course grading policy.

- Information on course examinations (two total). The midterm exam is on October 15th in class; the final exam will be held in class on the last day of classes (December 12). The final exam will be a 75-minute final covering the material since the midterm exam, not a comprehensive exam.

- Information on the written assignments, including suggestions for finding many digitized historical images that will likely prove useful for both papers in this class.

- Course warnings and resources: Plagiarism policy, information on the History Lab, in-lecture screen policy, and accommodations to ensure accessibility for McBurney students.

- Weekly outline of lectures and assignments, including number of pages assigned to be read per week in parentheses at the end of each week's title.

- Additional scheduled events: Map Library exercise will happen for section two weeks from now; Wisconsin Historical Society tours will happen in mid-October, after the midterm exam.

- Major assignment due dates. You should mark the evening review sessions for the midterm and final exams on your calendar and try to protect those times: 7:00-8:30pm on Thursday, Oct. 11, and Monday, Dec. 10 (both Mondays).

Final word: How should you take notes in this class?

- Draw on the lecture notes we will be posting online as close to lecture as possible--usually before lecture, but occasionally afterwards if the lecture has undergone significant revisions right up until the time it was delivered. Note sheets will generally include significant details (names, places, dates) that serve as evidence for the central arguments of the course. The lecture notes will also include important images from the class when those can easily be linked digitally. The "Suggested Readings" section on the notesheets are not required or assigned reading, but are just what the word "suggested" implies: suggestions for texts you might be interested in consulingt if you'd like to learn more about the subject of a particular lecture. The same is true of the many suggested links scattered through the note sheets: their purpose is to enrich your understanding by encouraging you to wander in search of additional knowledge about landscape features and places that interest you.

- DO take your own hand-written notes on themes, big arguments, questions, or details that strike you as being especially important or interesting as you are listening to lecture. You can couple your own notes with the more detail-oriented lecture notes that we're posting online.

With those logistical details out of the way, let's dig into course material:

Why Study Landscape History?

Why study landscape? Why care about it? This lecture will describe the intellectual lineage of this course. One obvious opening question to ask when asking "Why study landscape?" is definitional: "What is landscape?"

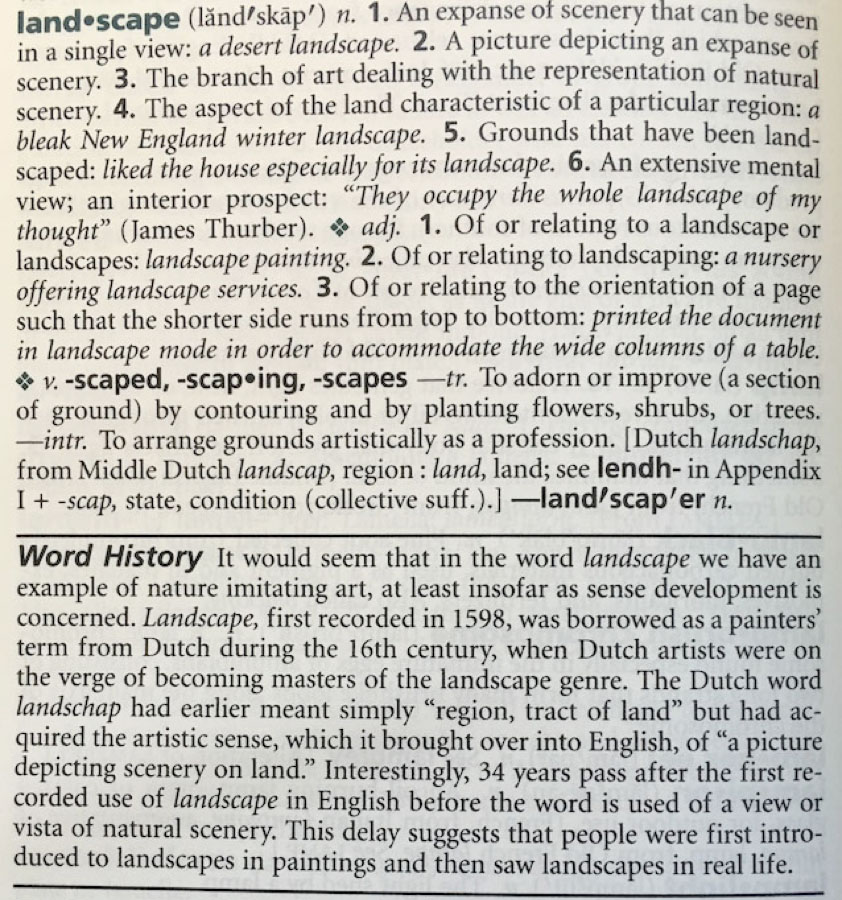

Definition from American Heritage Dictionary, 4th ed., 2000: Notice in particular definitions 1 ("n. An expanse of scenery that can be seen in a single view") and 4 (n. The aspect of the land characteristic of a particular region).

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed (2000)

The origin of the word "landscape" is Dutch, from the Netherlands in the late 16th century, when landscape painting was for the first time emerging as a major artistic tradition in European painting. The roots of 19th-century Romantic landscape painting go back to these earlier 16th- and 17th-century paintings. Notice from this lineage that the term "landscape" refers to representations of things in the world, rather than a more recent usage reflected in the title of this course: to refer to the world itself. The etymology of the term "landscape" also suggests a bias in the word towards that which is visual—places that are seen, that constitute a scene, that are framed like pictures. This privileges a visual aesthetic.

Landscape as a word has an intellectual lineage that goes back to elite viewers of landscapes who wanted to bring representations of places that they thought were beautiful, often while traveling, back to their homes. So notice that the word has the bias of a certain kind of class privilege built into it: a term originating with those who had access to the means to travel and the leisure time to enjoy touring.

By one definition (#1 in the American Heritage Dictionary's listing'), "landscape" can refer to any expanse of scenery that can be encompassed within a single line of sight. This means that the tradition of landscape has a bias towards the local, akin to what we discussed in lecture on Wednesday: studying landscape means paying careful attention to one place (e.g. Portage, Wisconsin, or the place about which you'll be writing in your final paper for this course) and then linking that one small place outward.

Notice: this course treats place as a starting point and then reaches outward geographically and backward temporally. We will never be satisfied in this course to look only at the local—but neither will we be satisfied only with abstract generalizations. Like the discipline of history itself, this course prizes complexity and heterogeneity, and will almost always to try ground its generalizations in particular places and objects and events. Holding the local and global in tension with each other is very much at the heart of this course.

This course is about the making of the American landscape, but given the immense diversity of regional landscapes in the United States, it might be more accurate to refer to landscapes in the plural. The title of this course is an homage to the 1955 classic The Making of the English Landscape by the English local historian and geographer William George Hoskins, which is a reminder that although we can refer to the landscape of the entire nation as if it were singular, that singular noun contains within itself a near infinitude of diversely plural landscapes.

How Should We Study Landscape History?

A few key observations about landscape:

- Landscape history brings to bear everything you know about a place: no discipline is irrelevant.

- Bodies of knowledge that are clearly relevant include history, geography, gology, ecology, botany, zoology, economics, sociology, engineering, architecture … virtually every discipline for which we have a name.

- Equally relevant to this course are questions of identity: class, gender, ethniticy, age, occupation, education, etc., and how these relate to land.

- Don't be intimidated by this list!

- Landscape is also intensely personal: what you experience in landscape is profoundly tied to your own past and what you care about.

This course will encourage you to ask (and to keep asking): Where am I from? We encourage you to think about how your own sense of self is connected to geographical places that have changed historically through time--both during your own lifetime and in the many years, decades, centuries, and millennia before you yourself lived in those places. We would like for your experience of this course to be as personal as it is intellectual.

How is this course structured? It's worth considering how it could have been organized:

- By period;

- By processes of landscape change (e.g. "geological processes," "colonial and imperial processes");

- By places/regions;

- By objects or landscape elements (e.g. "fire hydrants," "forts," "railroad and waterways");

- By stories.

Our syllabus leans towards the last of these options as a vehicle for an eclectic mixture of all five options. Throughout the semester, we'll be seeking out rich stories to help us understand the periods, processes, places, regions, objects, and elements that have constituted the American landscape as it has changed through history.

This course as two primary objectives:

- To give you an understanding of how the American landscape has changed over time. It will argue that the United States (along with its indigenous and colonial precursors) has been a dynamic nation whose many peoples have all left signatures on the land. This course will tell stories of place-making and landscape-shaping, explaining the what ("what changed?"), the how ("how did it change?"), and the why ("why did it change?").

- To hone your ability to read the landscape yourself. In a place, how do you orient to seeing what's there? What evidence can you see in the landscape that can help you understand how the place came to be? This course argues that landscapes are among the richest of historical documents, too often underappreciated in their richness.

Traditions of Landscape History at UW-Madison

The University of Wisconsin-Madison as an institution has a surprisingly dense history of supporting what today we could call the study of landscape history. Many individuals associated with UW-Madison have contributed to fields relevant to this course, and we in this course are part of continuing a long tradition. Because of the 1862 Morrill Act, which gave land to the states to create universities devoted to the "agricultural and mechanic arts" (hence, colleges of agriculture and engineering, initially resisted by the Madison faculty), UW-Madison is "land-grant institution" committed to both the liberal arts and the applied sciences. (If you want physical evidence in the landscape of the Morrill Act's legacy, look at the decorative motifs on the building across Bascom Hill from us where the Education School is now located--the more you study those decorations, the more you'll see evidence that it was once the home of the Engineering School that the Morrill Act made possible.)

UW-Madison's dual personality of combining pure and applied knowledge helps explain why this school has in its history so many individuals committed to studying landscape change:

John Muir, 1838-1914, nature writer and conservationist.

Frederick Jackson Turner, 1861-1932, UW History Department. Turner argued that U.S. history was a story of land-taking, and that the nation was forged in the long process of migration and—in his language—"struggle with the wilderness." We now recognize this phrase as misleading because the so-called "empty land" of Turner's "frontier wilderness" was home to a great many native peoples when white settlers began to occupy it. Despite the many problems of Turner's frontier thesis, though, we should also recognize that his work laid the foundations for ways of doing history that paid close attention to the role of land and ordinary people in shaping the American past.

Edward A. Birge, 1851-1950, UW Limnology and former UW President. Birge pioneered studies of Lake Mendota that continue to this day, and that have made Mendota among the most highly studied bodies of water of its size anywhere in the world. Birge did pioneering research that helped create the science of lake ecology by studying the body of water right next to this campus: science in place.

Charles Richard Van Hise, 1857-1918, UW President who, along with his roommate Robert M. La Follette, Sr., pioneered "the Wisconsin Idea" that "the boundaries of the University are the boundaries of the state." Van Hise was also author of the first textbook on conservation history published in the U.S., The Conservation of Natural Resources in the United States.

Benjamin Horace Hibbard, 1870-1955, UW Agricultural Economics and author of A History of the Public Land Policies about U.S. laws governing distribution of the public lands, a topic we'll study later in the semester.

John T. Curtis, 1913-1961, UW Botany, who pioneered ecologically place-based rather than taxonomically species-based studies of local biota, especially his great classic 1959 book The Vegetation of Wisconsin.

Norman Fassett, 1900-1954, UW Botany and director of the UW Herbarium. Author of Spring Flora of Wisconsin.

Andrew Hill Clark, 1911-1975, UW Geography, author of pioneering works on people-environment interactions in his native Canada and elsewhere.

James Willard Hurst, 1910-1997, UW Law School, one of the nation's most influential legal historians, whose research often focused on land and natural resources, and whose classic Law and Economic Growth was a massive study of the role of law in the history of the lumber industry of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Wisconsin--an industry that profoundly shaped the landscapes of this state and many others.

Aldo Leopold, 1887-1948, founding member of UW-Madison's Wildlife Ecology department. You know him as one of the most important American conservationists in the first half of the twentieth century, author of A Sand County Almanac. He joined UW as chair of the Department of Game Management. In 1938, Leopold taught for the first time his influential course Wildlife Ecology 118. Its syllabus declared: "The course aims to develop the ability to read landscape, i.e. to discern and interpret ecological forces in terms of land-use history and conservation." Our own course, History / Geography / Environmental Studies 469, is partly an homage to Leopold's course.

How do we know what Leopold taught? Most of Leopold's own course records haven't survived, but we do have detailed notes taken by two of Leopold's students: Lawrence G. Monthey (in 1938) and Grant Cottam (in 1946) who have deposited their course materials in archives where scholars can consult them. We see from their notes of Leopold's diagrams that the course modeled the type of place-based thinking that he and his students prized: deeply place-based. See, for example: "Progress on the Prairie;" "Central Wisconsin Marshes;" "History of Northern Wisconsin." Incidentally, Grant Cottam was for many years a Botany professor here at UW-Madison, and his notes for Wildlife Ecology 118 are available online: http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/AldoLeopold/AldoLeopold-idx?type=header&id=AldoLeopold.ALCourseMat&isize=text

Jim Zimmerman, 1924-1992, naturalist at the UW Arboretum who was trained by Leopold, and his successor Virginia Kline, 1926-2003, trained by Grant Cottam and also continued that tradition, also of the UW Arboretum.

Notice: all of these thinkers focused their research on local places and local processes in order to draw conclusions that proved of broader relevance and importance. This course, following the lead of these thinkers, will try teach us to do the same.

Other Traditions

The intellectual traditions at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for studying people and history in landscapes--on the land--are thus rich and deep, but there are many others. The list could go on forever, but would surely include:

- As I mentioned earlier, the title of this course is an homage to the 1955 classic The Making of the English Landscape by the English local historian and geographer William George Hoskins, 1908-1992. I'll show you in upcoming lectures how much we can learn from the work of Hoskins and other scholars and scientists who have studied the landscapes of the British Isles, which are in many ways far more legible than those of most of the United States. Anyone who studies landscape history today owes a debt to Hoskins and his work.

- The French Annales school, associated with the multidisciplinary journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale founded in 1929 by the historians Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch and a number of others. These scholars argued against traditional histories that focused on the actions of individual political and military leaders (most of them men), focusing instead on institutions, technologies, and the practices of ordinary people in shaping lands and environments. Much of the work they did could be recognized as landscape history today.

- The school of historical geography at the University of California, Berkeley associated with the work of Carl Sauer (1889-1975) and his students, which, along with Andrew Hill Clark here at Wisconsin, saw geography and history as inextricably linked as a way of study people in time and space.

- The highly eclectic, playful, creative work of the cultural geographer J. B. Jackson, 1909-1996, who founded the journal Landscape in 1951 and who fostered approaches to landscape history that remain influential today. Jackson in particular believed in studying vernacular and popular culture to understand the ways in which ordinary people as opposed to elites had shaped landscapes. He also modeled a very playful, interdisciplinary approach that I'll try to encourage us to emulate in this course.

- The rise of environmental history in the 1970s and 1980s sought to reframe the study of history by looking at the role of plants, animals, and non-human nature in past human societies. My other big lecture course, History / Geography / Environmental Studies 460, American Environmental History, provides an overview of this field, and I'll try not to repeat its contents in this course. We'll focus less on environment than we do on landscape in this course, though the two are of course inextricably linked to each other.

- American Studies and Art History have both made vital contributions since at least the middle of the 20th century in such classic works as Henry Nash Smith's Virgin Land, Leo Marx's The Machine in the Garden, and Barbara Novak's Nature and Culture to help us see the ways in which representations of landscape are just as important as landscapes themselves in shaping our understandings of landscape history.

One Last Tip: How Not to Get Lost in the Forest Amid All the Trees

And so on and on and on. By now, I'm guessing your heads are spinning with all the references I've been throwing at you, and that's an experience I'm sure you'll have repeatedly as the semester progresses. You've probably been asking yourself, "Wait! How much of this do I have to remember? This is feeling overwhelming. There's too much to know!"

And that's precisely right: there is too much to know, a point to which I'll return more than once before we're done. No matter how big or how small the landscape you're studying, the things you could try to know about it are essentially infinite.

I once sat on the shore of Lake Michigan with an applied mathematician who remarked that he could spend the rest of his life trying to calculate the movement of a single wave as it crashed on the beach in front of us, but, try as he might, he would never finish that work.

He said this not in frustration or despair, but in pure wonder: for him, the complexity of that single wave was a miracle, something so astonishing and so beautiful that it filled him with joy to contemplate.

That's what I'd like you to try to remember when you're beginning to feel overwhelmed by the landscapes we study in this course. The secret is not to try to remember everything you can about a given place or landscape, because that's actually impossible.

Instead, remind yourself that what you learn about landscape in this course is less important than how you learn it, and the tools you use to figure it out.

The answers are less important in this course than the questions.

The particular things we look at are less important than the ways we look at them.

Because we'll be borrowing insights from so many different fields, the lenses through which we look when we "read a landscape" are at least as important as the landscape we're reading.

This is not to say that details don't matter. They do. They matter enormously, because without the particulars we find in a landscape--the plants, the animals, the rocks, the contours, the flowing waters, the buildings, the infrastructures, and most of all the people--it wouldn't be the landscape it is.

But what you do with those details, how you make meanings from them, matters most of all.

After taking this course, I hope you'll approach every new place you encounter by saying to yourself: "This too was part of the making of the American landscape. I wonder how it came to be this way. I think I'll try to try to figure that out."

The pleasures of reading the landscape arise less from the knowing than from the not knowing ... while remembering that you have nearly endless tools for figuring out what you want to know.