|

|

|

||||

Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer

|

Information To Notice |

|

If you’re reviewing such primary documents as maps, note first the map margin, which explains information in a map in a manner similar to a book’s table of contents. Be sure to pay attention to such features as scale and direction, when relevant, because you want to make sure you take accurate notes. See our Maps and GIS page for more information.

Sometimes you’ll take notes on primary documents, such as journals or speeches. The following are pages excerpted from a speech given by George P. Marsh, a U.S. representative from Vermont (1847). The speech can be found through the Library of Congress’s The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920, Digital Collections.

(click for larger image)

Address Delivered before the Agricultural Society of Rutland County (1847)

by George P. Marsh, Library of Congress digital collections

Based on our suggestions of “Information To Notice,” you would want to write down various points and ideas from these pages. For example, you should note the following:

If you’re writing a paper about the early years of the U.S. conservation movement, Marsh’s speech offers rich insights. Reading through his speech, you’ll discover that he advocates government management of forestlands. Park management by federal and state governments is common today. But consider the time at which Marsh talks about these ideas – 1847. How common was government management of forestlands during this period? How did people react to his speech? When you ask probing questions you enhance the arguments in your paper.

Also note main and minor arguments that Marsh makes during his speech. In his opening paragraph, he says that the Agricultural Society’s interests and efforts extend beyond soil. He suggests an interdependent relationship between soil, herdsman, and the mechanics of labor, and proposes such a relationship has important implications for society. This seems like an important idea and one you would want to include in your notes for further consideration.

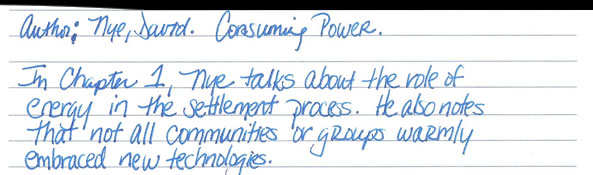

Notes taken about a case study of an olive orchard

(Emma Schroeder 2008)

Taking notes is about more than writing down dates, names, accurate quotes, and publisher’s information. While we can’t overstate the importance of having this information, we also can’t emphasize enough that you want to consider how author’s claims differ from or are similar to others. You also want to assess how author’s ideas can contribute to your own work. The following section offers more ideas about making connections as you’re collecting information.

If you want to craft a strong argument, reading critically and taking good notes go hand-in-hand. Think about how the material you’re reading could contribute to your overall argument, as well as sub-arguments. You’ll want to include your ideas in your notes, but be careful to specify when you’re writing your own ideas and when you’re synthesizing the author’s.

'

'

Book Flagged with Note Tabs

(William Cronon, 2008)

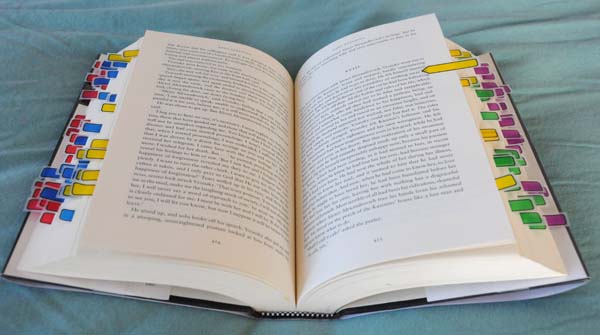

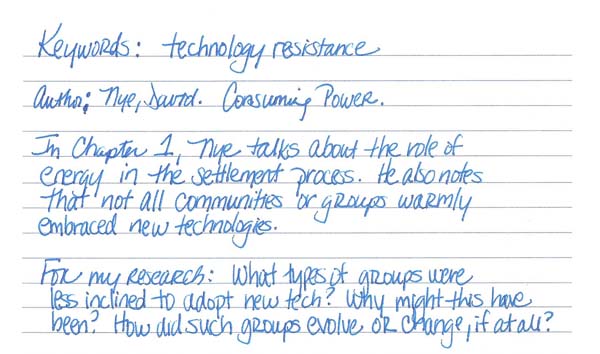

Below we’ve provided a page of notes taken on David Nye’s book, Consuming Power (2001). Even if you haven’t read the book, you can glean the book’s focus from the notes.

(Emma Schroeder, 2008)

Reading through this first page of notes, what themes emerge? Energy is a repeated theme. Note that the third item suggests the note-taker sees an idea emerging that energy can change people’s concept of time.

This is an important idea throughout Nye’s book. As you read, you’ll want to note the importance of a claim. Ask yourself whether it’s a main point, supporting point, or whether it’s a statement that may not actually be relevant to any main or supporting points. You don’t want to misinterpret a statement and its significance.

You may not know right away the significance of an author’s claims. That’s fine. In the fourth point on the above page of notes, the note-taker includes information about the relationship between farms and sawmills. She asks, “How does this play out?”

This is a good way to alert you to ideas that may be significant. Keep track of these ideas and your questions in a research journal. You may want to include ideas or claims that seem important to you on index cards and create one or more keywords for the idea so that you can draw connections among your notes. For example, you might create an index card for the fourth point with the keywords “technology resistance” to see if other like ideas surface throughout the book.

(Cathy DeShano, 2008)

This first page of notes is important because it includes ideas the reader encountered in Nye’s first chapter. She has other pages of notes from this chapter, and we expect you’ll also have multiple pages of notes on each of your sources. While it’s important for you to include notes on the ideas you’ve read, you’ll have a hard time crafting your own paper if your notes are only summaries of authors’ claims.

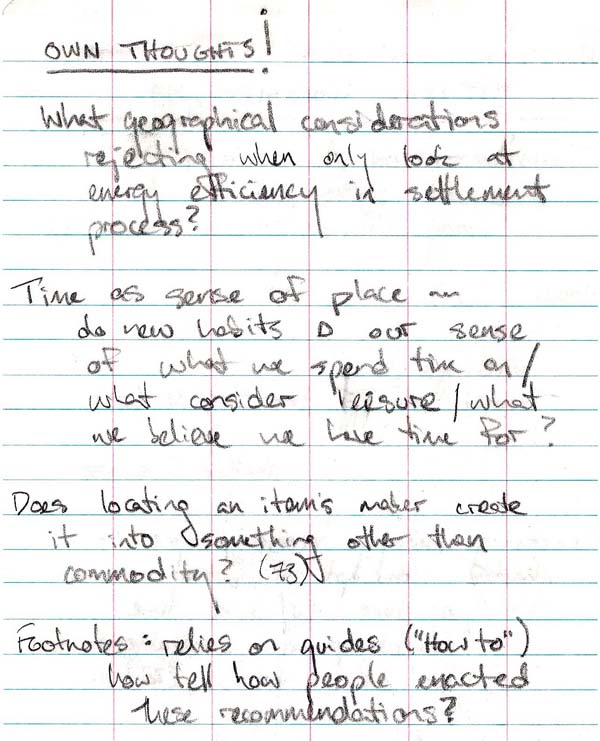

Below is a page that accompanies the page of notes included above. Notice immediately that the note-taker has distinguished this page of notes as her “own thoughts.”

(Emma Schroeder, 2008)

Create note pages that include your own thoughts so that you’re crafting your own argument throughout the research process, rather than waiting until you’ve read everything. You can see from the above that the note-taker considers geography and time important elements. She may be interested in these for her own paper.

If you look at the first note above, you’ll see the note-taker wonders what geographical considerations the author ignores by looking only at energy efficiency in a settlement process. In your own notes, you’ll also want to ask questions or make statements about those ideas you may disagree with or have reservations about. Also note when you agree with ideas.

She also has included a point about footnotes. Footnotes and bibliographies reveal important information about how authors build their claims, such as the sources they use, as well as the scholarly ideas with which they are engaging.

These notes do even more than give us insight into the note-taker’s thoughts about the book. They also give us a clue about how David Nye positions his claim with respect to its range of application.

What clue do the notes provide about this? Well, go back to the first note on the “own thoughts” page. She suggests that the author’s narrow argument about settlement process may have geographical implications. We can infer from this that the author’s first chapter focused on settlement processes and energy. We wouldn’t want to draw any conclusions from this chapter, however, about energy and wild spaces since this isn’t Nye’s focus for the chapter. In your own notes, you may want to be more explicit about the position – or range – of an author’s claims.

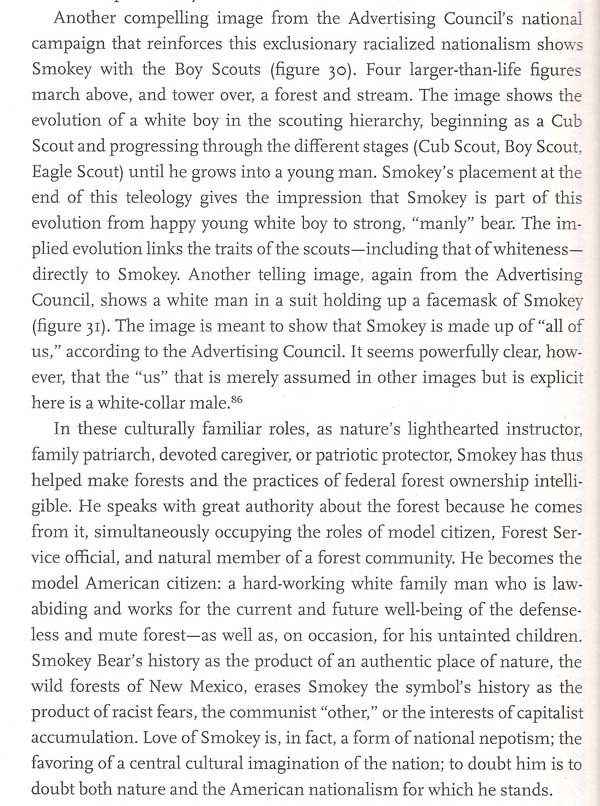

Now that you’ve got the basic information about features to pay attention to while taking notes, let’s put some of that to practice. Let’s say you’ve decided to write a paper about the role symbols may play in people’s attitudes about environmental issues. In his book, Understories (2006), Jake Kosek talks about Smokey the Bear and attitudes toward him among Hispanos, Anglos, and Native Americans living in northern New Mexico. The following passage is from page 216 of Kosek’s book.

Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico (2006) by Jake Kosek

What would you include in your own notes about this section? Following is a checklist of the notes that we’d suggest.

If you engage in these practices while you’re reading and taking notes, you’ll have a good start toward a strong paper with focused arguments because you’ve been making connections between ideas, others and your own, throughout the note-taking process.

Once you decide on a research question, you must gather evidence to help you answer your question. Finding documents relevant to your question takes creativity, time, and organization. While you may have serendipitously stumbled upon your topic, structuring your search ensures that you are:

Keeping notes on your research process is therefore integral to your research process. A research journal will ensure you are not replicating searches and force you to continually ask yourself:

In this section, use your creativity to design a wide research net that will capture as much evidence as possible. Record where you will likely have to go for information. Which libraries will be important to visit? What types of documents are you hoping to find? What databases will you search first? Think broadly about document types and locations to prevent missing key sources; but remember no matter how much planning you do, it is often the documents you were not expecting that are the most valuable to your research.

Write down the research paths you have traveled. Why waste time repeating database searches you have already done? Keep lists of:

This section differs from your original research plan as it is a place for you to use the documents you already have to inform further research. You need to use your critical reading skills to create a list of Library of Congress Subject Headings, call numbers, and citations that cascade from the research you have already done. This section is the most important part of your journal. We didn’t want it to get buried, so look at Keeping Track of the Research Train for how best to go about this part of the journal.

Keep notes on how each source you have found is relevant to your work. Does this article help you explain the theory behind your question? The methods you will use to answer your question? Or is it evidence to back up one of your claims? How does the source relate to the other pieces of evidence you have?

It is important to remember that your sources must always be in dialogue with your larger question; if the sources are leading you somewhere you were not expecting, you will only realize this by constantly trying to connect the pieces together in a way intelligible to you and others.

This is the most important part of your journal and the most fun. Every document you find has a train of documents related to it. It is important that you read sources completely to understand their connections to a wider array of evidence. Reading a source does not mean you begin and end with the text, instead you must read a source from its title page to the last page of the bibliography. Then you will be able to expand your search using Library of Congress Subject Headings, call numbers, and citations in your original document.

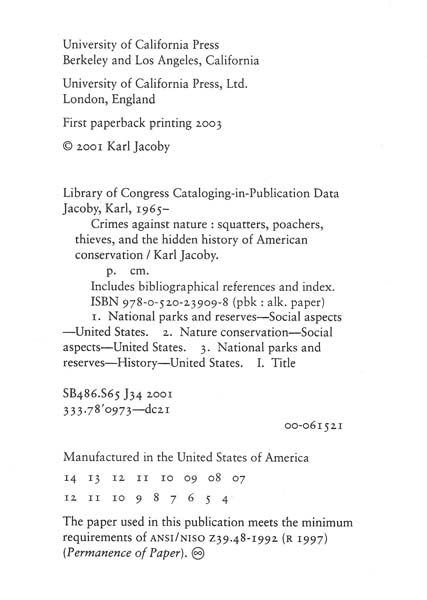

Look at the Library of Congress Subject Headings and keywords of salient documents you have found to identify other terms that may match what you are looking for. For example, if you were interested in researching the history of America’s national parks and you searched for “National parks and reserves” you may have found Karl Jacoby’s Crimes Against Nature (2001), the copyright page of which looks like this:

Copyright Page, Karl Jacoby's Crimes Against Nature (2001)

Since you already looked up “National parks and reserves” (the first Library of Congress Subject Heading), you would record

Nature Conservation – Social Aspects – United States

National Parks and Reserves – History – United States

in a “Keywords to research” section of your journal.

Library collections are arranged so that books with similar topics are arranged together on the shelves. Recording call numbers will tell you the subjects you have looked at and where there may be more books salient to your research. For instance, Crimes Against Nature has call number SB486 S65 J34 2001; SB denotes that this book is catalogued under the subject subclass “Plant Culture.” You may then go and wander the shelves in the S and SB section to see what other books may be pertinent.

Books in Steenbock Library, University of Wisconsin—Madison

(Emma Schroeder, 2008)

Other call number classes that are particularly relevant to environmental history research are:

Citations and creating a document genealogy

Reading critically requires that you read the citations of each source to identify previous scholars the author is in dialogue with. You can create a genealogy (think of this as a family tree) of scholarship from one article that will lead you to many more documents salient to your work. If you were looking into the ways in which technology changed farmer’s perceptions and use of the landscape around them, you may have found David Nye’s Consuming Power (2001). Rather than just reading the text, you may have noticed footnote number 26 on technical advances:

Consuming Power (2001) by David Nye

This in turn could lead you to Paul W. Gates’ The Farmer’s Age (1960), whose bibliography looks like this:

The Farmer’s Age (1960) by Paul W. Gates

This type of bibliography (a bibliographic essay) is particularly helpful as it contains not just specific sources, but source categories you may be interested in pursuing further (travel journals, agricultural society newsletters, agricultural journalists, etc.). Bibliographic essays also include an author’s notes on how each source type is valuable. Another type of bibliography to look for is an annotated bibliography, which will give you a few sentences describing each source.

If you followed this genealogy one step further, you reach the primary documents underlying Gates’ work. One of these is Facts for farmers; also for the family circle: a compost of rich materials for all land-owners, about domestic animals and domestic economy; farm buildings; gardens, orchards, and vineyards; and all farm crops, tools, fences, fertilization, draining, and irrigation; illustrated with steel engravings (1864) edited by Solon Robinson, whose pages provide every juicy detail the title promises and more, including pages like this:

Facts for Farmers (1864), edited by Solon Robinson

Following this train, and recording all citations you think are relevant in your journal, allowed you to follow your evidence from how contemporary writers view technology’s effects on farmer life (Consuming Power) to how technology was addressed 40 years ago (A Farmer’s Age) to how farmer wives in the nineteenth century were balancing which fuels to use for home lighting and which new grain mills farmers thought were best to adopt at the time.

Just as important as knowing what to take notes on is deciding how and where to physically record your thoughts. There are many options for you to choose from, each of which work for different people. We have listed some and their pros and cons in the table below. Remember, your notes on one source do not exist in their own universe. The physical tool you use should help you create links between your documents. Besides that, it is up to you to choose how to organize your research.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As discussed earlier, a journal is an essential tool for people as they research topics. You can organize information in your journal, and they’re easy to pick up and take with you so that you’ve got them always at hand.

You may want to consider additional tools for note-taking. Some that many of you already may use are word-processing documents or spreadsheets. If you use such computer programs, make sure that you back up your information to a CD-rom, flash drive, or other location on a regular basis. You don’t want to lose information because your computer dies.

Online software programs such as RefWorks, EndNote, and EndNote Web are valuable options for creating and managing personal searches and citations for documents you have used. Such software programs allow you to search library databases for materials, if your library subscribes to such a service. Once you find the materials you’re looking for, you can ask the software program to store and organize the information based on settings you create. For example, you may create a group called “Environmental History” that includes citations you think would be relevant for such work. An EndNote Web page of materials that you’ve identified and group may look like this.

EndNote Screen Shot (click for larger version)

You’ll want to visit the RefWorks and EndNote Websites for full descriptions of the products and to consider which options would work best for you.

Let’s say you’ve decided to research the early years of the U.S. conservation movement. Your search may lead you to the Sierra Club. You find a reprint of Joseph Le Conte’s “Ramblings through the High Sierra” in a Sierra Club Bulletin published in 1900. The following is an excerpt from Le Conte’s writings, located through the Library of Congress’ The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920, digital collections, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/conshome.html.

(click for larger image)

“Ramblings through the High Sierra” in the Sierra Club Bulletin (1900) by Joseph Le Conte

What kind of information might be important to you? Think about the points raised in previous paragraphs. What are some of the significant ideas the author touches on here? Consider whether he has first-hand access to the information he’s writing. According to the Library of Congress Website, the journal was privately printed in 1875 and published in the Sierra Bulletin in 1900. Does this suggest anything? Notice that the author includes a general date, August 11. This could be useful down the road. He writes about glacial evidence, weather, and the landscape. Think about how such information could prompt new investigations or support a research process.

Booth, Wayne, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. The Craft of Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Endless Scholar. http://endlessscholar.com/category/note-taking

Library of Congress Classification Outline. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/lcco/

Library of Congress Learning Page. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/learn/index.html

Lifehack.org. http://www.lifehack.org/articles/productivity/the-ultimate-student-resource-list.html

Mann, Thomas. The Oxford Guide to Library Research. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Primary Sources at Yale. http://www.yale.edu/collections_collaborative/primarysources/index.html

Demory, Pamela. “It's All Storytelling: An Interview with Michael Pollan.” Writing on the Edge. Davis, Calif.: University of California, Davis. 2006. Vol 17, No. 1. Retrieved online Nov. 16, 2008. www.michaelpollan.com/press.php?id=65

Gates, Paul W. The Farmer’s Age: Agriculture. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960.

Jacoby, Karl. Crimes Against Nature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Kosek, Jake. Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico. Duke University Press, 2006.

LeConte, John. “Ramblings through the High Sierra.” Sierra Club Bulletin. 1900. Vol 3, No. 1. Retrieved from the Library of Congress on Oct. 26, 2008. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/conshome.html

Marsh, George. Address: Rutland County Agricultural Society. Rutland, Vt.: Herald Offices. 1847. Retrieved from the Library of Congress on Nov. 21, 2008. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amrvhtml/conshome.html

Nye, David E. Consuming Power: A social history of American energies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Robinson, Solon (ed). Facts for farmers; also for the family circle : a compost of rich materials for all land-owners, about domestic animals and domestic economy; farm buildings; gardens, orchards, and vineyards; and all farm crops, tools, fences, fertilization, draining, and irrigation; illustrated with steel engravings. New York: Johnson and Ward, 1864.

Page revision date: 30-Apr-2009