|

|

|

||||

Learning to Do Historical Research: Sources

|

Governmental Body or Process |

Documents Produced |

Environmental History Example |

Federal Agency |

|

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) technical report Chesapeake Bay: Introduction to an Ecosystem (1995) |

U.S. Census |

|

1880 Census map of “The Outline of the Physical Geography of the State of Louisiana” |

Congress: Passage of a bill through the Legislature |

|

National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 A 1968 U.S. House hearing before the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Industry Problems. |

Court Cases |

|

Karl Jacoby’s Crimes Against Nature. Jacoby uses local court records to paint a complicated picture of how people responded to the creation of a state park in the Adirondacks. |

Executive Branch |

|

Executive Order 11990—Protection of wetlands (Carter, 1977): “... in order to avoid to the extent possible the long and short term adverse impacts associated with the destruction or modification of wetlands and to avoid direct or indirect support of new construction in wetlands wherever there is a practicable alternative …” |

How Does Government Work?

Knowing what documents come from what parts of government is a key part of your success, however, that means you need to know how government works. If you are interested in understanding more about governmental structure, we’ve created a quick civics guide which you can read by clicking here. Take a peek; it will help immensely in your search.

Federal government records are easy to find compared to state and local records; the mission of the Government Printing Office (GPO) is to distribute and manage all information that is created in the federal government. Government document depositories exist in all 50 states (sometimes more than one per state). These depositories receive all materials produced and distributed by the Government Printing Office.

Federal Depository Symbol http://www.gpoaccess.gov/fdlp.html

Your first step in accessing federal documents should be to identify the nearest government depository. You can do this by going to the GPO website http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/FDLPdir.jsp (click on “FDLP Public Page”). All depositories will have a government documents librarian—find this person and ask for help!

If you are not near a depository the next best route is to search GPO Access (http://www.gpoaccess.gov/index.html ), the official online access point for government publications. Your search, however, should not be limited to the Internet. GPO Access is not a complete historical collection—many older documents have not been digitized and therefore the full-text versions of documents are limited. Make sure to consult a print index, such as the Monthly Catalog of United States Government Publications, or your library catalog.

There are many print publications and indices to help you search for pertinent documents. We have included a “Search Tools Considered” section at the end of this page—you should look at it to see what resources would best help your specific search.

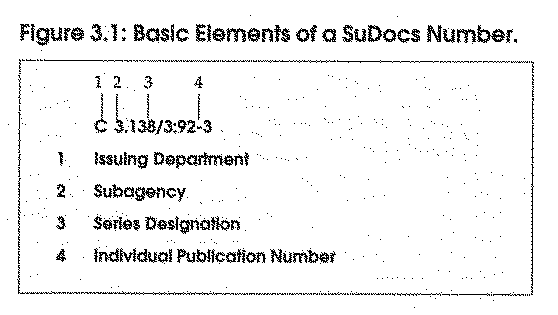

Federal government documents are organized using a different classification system than all other publications. Rather than being cataloged by the Library of Congress or Dewey Decimal system, government documents are organized by the Superintendent of Documents (SuDocs) classification system. Government documents are arranged according to which department issued them—for example, all reports from the Department of Agriculture are together, as are all documents issued by the Environmental Protection Agency. A sample SuDocs record looks like this:

From Sears and Moody, Using Government Information Sources (1994)

This means that you cannot simply browse the shelves and expect to find everything on your topic—documents relating to the Chesapeake Bay may be in the A section (Agriculture) or the C section (Commerce Department) or the EP section (Environmental Protection Agency). You must be proactive in casting a wide net through many agencies and departments in order to find all of the information relevant to your topic.

If you go back to the Rachel Carson example, it turns out that Carson’s testimony is listed under the SuDoc number, Y.4 C73/2: 88/66. Once you know the SuDoc number, visit the stacks. “Y.4” indicates a document from a working committee of Congress, so you know you are looking for congressional records. Hearings are compiled into books (catalogued by SuDoc number) and each hearing will start with a table of contents that outlines the testimony and arguments put forth before the committee on that day. Find Rachel Carson, listed as “Biologist and Author” in the table of contents for the hearings. Flip to the right page, and there you are, back in 1963.

Federal agencies implement and oversee government programs. Agency document collections can turn you on your head, but they can also help you choose a great research topic. Sometimes you have to let the documents guide you; if you aren’t sure what you want to write about, head to the stacks and take a gander.

All government agencies produce documents through the programs they administer. Documents such as scientific reports, maps, recommendations, helpful hints to United States citizens, and statistics are produced by agencies ranging from the Department of the Interior to the Chesapeake Bay Commission to the Army Corps of Engineers.

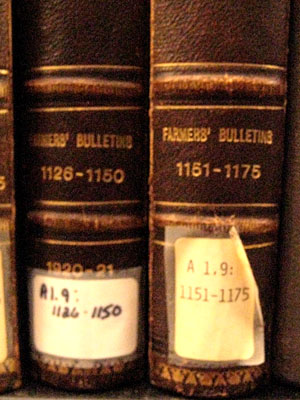

Pacing the library trying to decide on your next paper topic, you decide to get lost in the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) stacks. Once you start browsing, you quickly realize that the USDA is involved in more issues than just farming. It produces documents that are full of information relating to land use, transportation, commerce, and water rights. Scanning the shelves the first thing you see is a volume marked “Office of Road Inquiry.” But you really aren’t that interested in road engineering, which seems to be the main focus of the publication. You move on with your search and next find a whole shelf of Farmers’ Bulletins.

Farmers’ Bulletins, Steenbock Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison (Emma Schroeder 2008)

Inside the Farmers’ Bulletins, the range of articles seems endless: taking care of boll weevils, how to market your wheat crop, and home gardening methods. The bulletins contain information specific to Southern and Northern climates, and even city gardens.

Introduction to Farmers’ Bulletin 936, The city and suburban vegetable garden

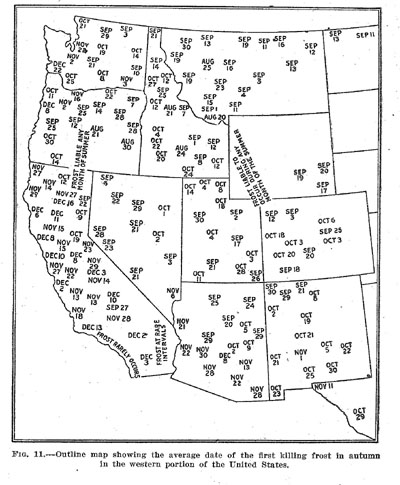

You find a huge range of information presented within these documents: maps, lists of vegetables to plant, frost times, and recommendations for how much money you should spend on seeds.

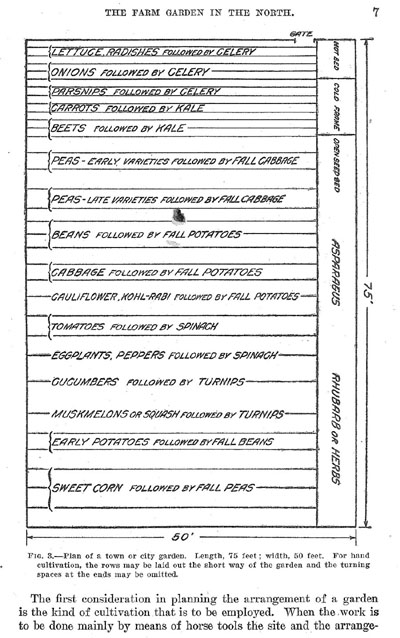

Garden plot map in Farmers’ Bulletin 937, The farm garden in the North

Map of killing frost dates in Farmers’ Bulletin 937, The farm garden in the North

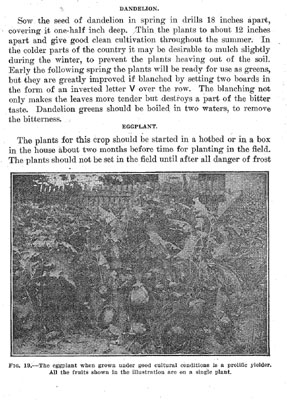

How might the USDA use the information it gathers on each region to make policy decisions? Questions crowd your head about how the USDA has used its research historically, what kinds of land use practices the agency has promoted, and if those practices have changed over time. Old Farmers’ Bulletins and USDA reports even show maps of weather patterns—could you find similar maps now to see how climate has changed and affected growing practices? What vegetable varieties has the USDA recommended in the past? You see that in the North, the 1918 publication explains how to grow dandelions. Why might someone in 1918 want to grow a weed?

Page from Farmers’ Bulletin 937, The farm garden in the North

For eating! The idea that the USDA could influence what kinds of crops people planted (and perhaps American nutrition) intrigues you – you realize that this influential agency is not only a research institution, but that it works to disseminate information as well. You spot an index to USDA government publications from 1901-1925 at the end of one shelf.

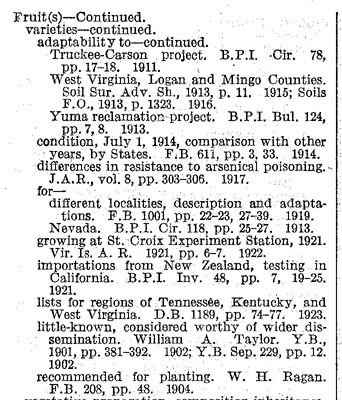

Section of Index to Publications of the USDA, 1901-1925

A title under “Fruit, varieties” catches your eye: Little known varieties considered worthy of wider dissemination, from the Agricultural Year Book (Y.B.) 1901, pp. 381. You head to the stacks again. This time, you are very surprised by what was considered a “little known variety”:

Pages from Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture, 1901

McIntosh apples are ubiquitous now. So what role did the USDA approval have in promoting the variety? This article was published in 1901, and may have helped the McIntosh, with its “adaptability to diverse conditions,” succeed in the US apple market. What effect might the McIntosh’s success have had on other kinds of apples?

By simply looking through USDA publications, and asking questions about the documents found, it is possible to form a research question. You don’t need to have a question before heading to the documents. It can be just as rewarding, if not more so, to let the documents you find determine the questions you ask.

Perhaps you are more interested in local government actions. You are learning about the 1918 influenza epidemic in a class and you start to wonder what steps your city government has taken in times of crisis. You head to the library, and a helpful government documents librarian points you to the stacks: onward to the shelves and shelves of documents created by the city of Milwaukee.

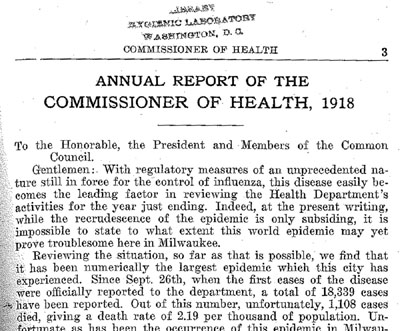

You find the proceedings of the School Board … Park Commission … Safety Commission … proceedings of the Common Council … ah-ha! Wisconsin Commissioner of Health! They must have recorded something on the epidemic. You open the bound collection of 1917-1920:

Wisconsin Commissioner of Health, Milwaukee. Report, 1918

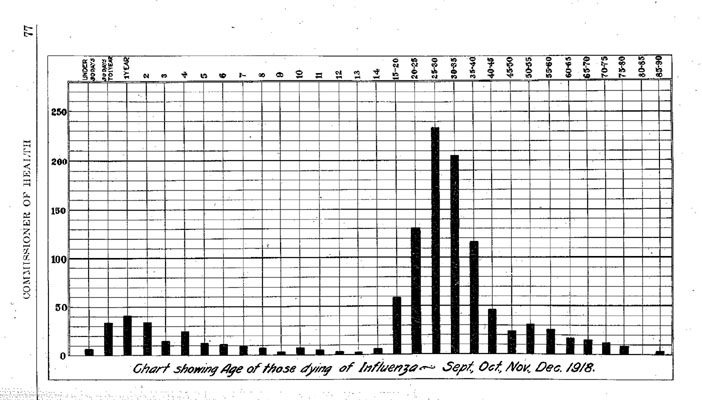

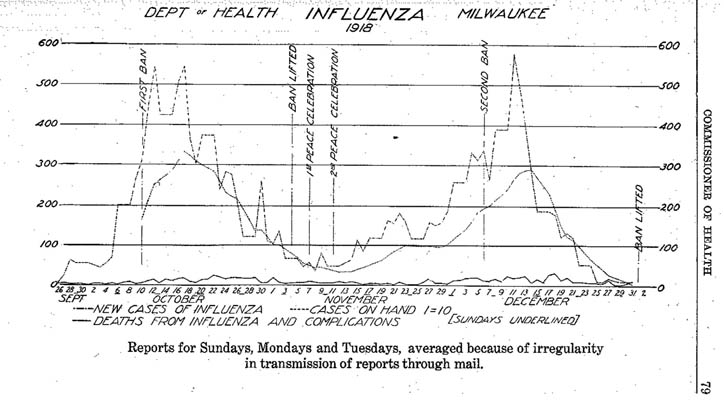

Milwaukee was hit hard. You see that in 1918 alone, 1,108 people died from influenza. You look further and find these graphs:

Graphs of Influenza Deaths in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1918

Not only have you found how many people died, but the ages of the casualties. It seems that the majority of people who died were between 20 and 40 years old—strange, as illness usually affects very old and very young populations more frequently. What were the younger adults doing that made them more vulnerable? You also notice that the occurrence of disease was not linear; instead different times of the year had different disease outbreaks.

Yet none of this tells you what the city was doing to stop the spread of flu. As soon as you get your nose out of the Commissioner of Health report, you see the Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, written by the School of Health and Sanitary Science. The book for 1915-1918 falls open to the last page:

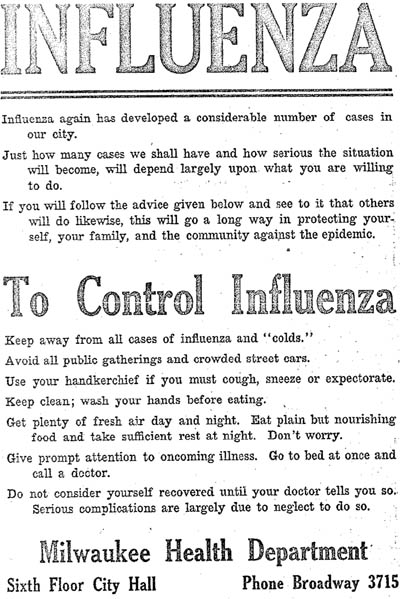

Announcement in Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, 1918

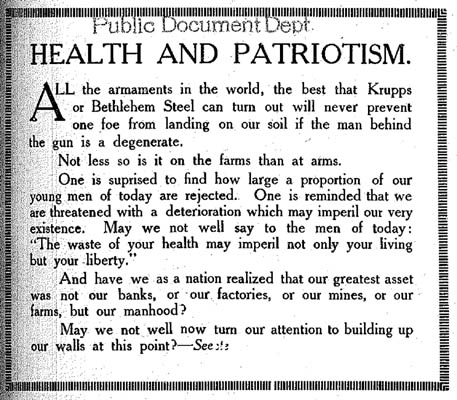

It seems that one of the main ways for Milwaukee to combat influenza was warning its citizens that they were partially responsible for preventing disease spread: “just how many cases we shall have and how serious the situation will become, will depend largely upon what you are willing to do.” Why would a city place such emphasis on personal sacrifice? You skim the rest of the volume and realize that the country was in World War I, and that every article exhorts people to conserve food, remain patriotic, and give of themselves for the community.

Announcement in Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, 1918

State, county, and local documents are a landmine of information. Unlike the cataloging process of federal government documents, there is no one agency to collect all of the evidence these smaller governments produce. When going to look for local documents, it is even more of a treasure hunt than when searching at the federal level. But, your search will pay off, and you don’t have to do it alone. Always ask the librarian!

An actual sign in the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Steenbock Library

In your research on the Endangered Species Act, you find a Science News Journal article from 1978 about a famous Supreme Court decision called Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) versus Hill. This case involved the construction of the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River, a project which began in 1967. The article tells you that in 1973, while studying the impacts of dam building on the river, an ichthyologist discovered an endangered fish called the snail darter. The snail darter was protected under the Endangered Species Act, a U.S. law designed to "…protect critically imperiled species from extinction."

Snail Darter, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Source: Wikipedia, WO-2553

In TVA v. Hill, the endangered species status of the snail darter held up the completion of the dam for several years. The case became so controversial that two members of Congress from Tennessee went to great lengths to finish the project, offering an amendment to exempt the Tellico dam from the ESA to ensure the project's completion. The amendment finally passed in November 1978. After years of litigation, the snail darter was moved to another river and the dam was completed.

Where would you start your research on the snail darter case? A great place to start is your campus law library. A law librarian can help guide you through the steps to find a law and subsequent amendments. Even without a law library you can access court records; below are several resources to help you begin your search.

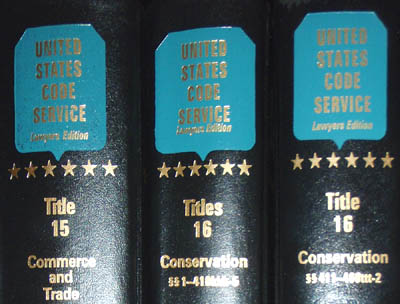

United States Code Service: The United States Code Service (USCS) is the set of texts that contain all the current laws and amendments passed by the U.S. government, starting with the U.S. Constitution. Lawyers refer to the United States Code Service texts to argue cases before courts. The U.S. Code is broken down by subjects called "titles." If you are looking for a particular law, look it up in the United States Code Service General Index and scan the shelves for the correct title of the U.S. Code. For instance, title 16 covers all laws concerning "Conservation," including the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The United States Code Service citation for the ESA is 16 U.S.C. 1531-1544, 87 Stat. 884. This is the place you will find a copy of the law as written, and the list of amendments. In title 16 you will also find the 1978 ESA amendment in reaction to the controversial snail darter case.

United States Code Service in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law Library Collection

The Code of Federal Regulations: Once a law has been passed by the Congress and signed by the President, the federal agencies responsible for implementation of a new program issue what is known as "The Code of Federal Regulations" (or CFR). The Code of Federal Regulations is a public document that explains the way in which the agency has interpreted the law and how it will be administered. Updates to the Code of Federal Regulations are issued every few months and contain regulations for new or amended laws. You can search for recent federal regulations online at the GPO Access website: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/index.html.

LexisNexis Academic: If you have access to it, the best resource for navigating briefs, opinions, and evidence surrounding a lawsuit is the search engine LexisNexis Academic. This program, and a similar one called Westlaw, are programs that synthesize all documents from a court case into one online database. LexisNexis and Westlaw case searches provide legal briefs and decisions, useful hyperlinks to other relevant legal cases, citations for the U.S. Code used in the case, and legislative history.

Law Reviews: It is worth mentioning that law review articles are also available through LexisNexis Academic. You can use this tool to search for scholarly reviews of a case which provide commentary on the legal arguments and impacts of a significant decision.

You can use LexisNexis Academic to help tell the story of the snail darter case. Once you are inside the LexisNexis database, click on the tab labeled “Legal.” Click on “Federal and Court Cases” on the left sidebar. Then type “Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill” into the case number box. Hit the “Search” button and a list of related documents will appear.

Under the first result you find a great summary of the arguments, decisions, and laws involved in the TVA v. Hill case. As you scroll down, you see a list of the key legal arguments and the citations for the laws that were invoked in making this decision. Scroll further and you will find the names of the judges who ruled on the case and a summary of each of their opinions. You can also go back to the left hand bar and search for “Law Reviews” on a case. Law Reviews offer opinions that can help you understand the historical significance of a case and how it has affected future decisions. Don't get discouraged by the magnitude of the information available to you on LexisNexis. Pick and choose what to read, and focus on the summaries.

Court cases have an enormous impact on the environmental laws and regulations used to protect our natural resources and human health. When you are conducting environmental history research, make sure to search for important legal decisions that may have affected the vast and layered regulatory landscape for your topic.

Government and legal documents represent a world of material that although tough to find, have an enormous impact on how we operate as a society. These important resources can show you how another generation lived, and what scientific, legal and cultural developments have occurred during the history of the United States. Don’t be intimidated! No one person could ever know how to find all of these sources. The important thing is to realize is that they do exist and that they are organized in an accessible way. If you are willing to commit your time and effort, the search for government documents has the potential to uncover an entirely new set of information—highly relevant, but lost in the stacks. Uncover it!

Government documents can be tricky to uncover, but there are many search tools to help you in the process. When beginning, remember to ask yourself:

Each of these questions will help you know where to look for documents and what kinds of documents may be available. Below are a few sources that will help you get started on your environmental history research.

Key Sources for Historical Government Publications

Guide to the National Archives of the U.S. 1974. National Archives and Record Service, General Services Administration.

Historical Statistics of the U.S. Millennial Edition: Earliest times to the present. Eds. S.B. Carter et al. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2006.

U.S. Congressional Serial Set, 1789 – present.

Indices of Government Publications

CIS/Index.

Monthly Catalog of the United States Government Publications.

U.S. Government Manual. 1935—. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

General Access to Government Information

GPO Access. http://www.gpoaccess.gov/index.html

LexisNexis Academic

State ‘Blue Books’

Statistical Abstract of the United States: The National Databook. US Census. Annual publication.

Thomas Search Engine (http://thomas.loc.gov/)

You’ve just started a research paper on cotton production in eastern Louisiana in the late nineteenth century. Where might you find an interesting primary document on your topic? Let’s take a look at the tenth Census of 1880. Pick out the volume titled “Cotton Production Part 1, Mississippi Valley and Southwestern States” and flip to the section on Louisiana.

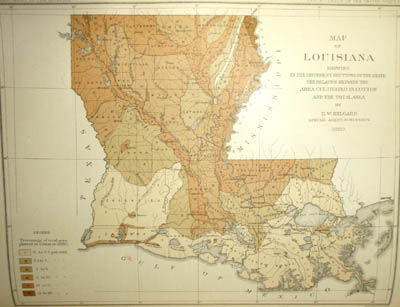

On page 110 is a beautiful color map titled “The Outline of the Physical Geography of the State of Louisiana” that shows the various agricultural regions of the state.

Map of Louisiana in the U.S. Census, Cotton Production Part 1, 1880

Look at the area north of Baton Rouge just below Mississippi. The nearby West Feliciana Parish contains “the Bluff Region,” described as: “the brown loam soil of this region maybe considered as first-class upland, and when fresh has readily yielded a 400-pound bale [of cotton], or 1,300 to 1,400 pounds of seed cotton per acre.” Read further and you learn that the Bluff Region contributed 5.6% of the state’s total cotton production in 1880.

Now check out another map that shows you what percentage of the total land in each region was planted in cotton:

Map of Louisiana in the U.S. Census, Cotton Production Part 1, 1880

You can tell from the shade of brown that between 1-10% of the land around Baton Rogue was planted in cotton in 1880.

Take a look at page 158 for individual statistics. West Feliciana Parish is listed as follows:

What can you learn from the 1880 Census about cotton production in east Louisiana? Census records are snapshots in time of a place and of a society. Try to imagine yourself in Baton Rogue around the turn of the 20th century. How might the agricultural nature of a region shape the economy and culture of a place?

DO

DON’T

An Explanation of the Superintendent of Documents Classification System. http://www.access.gpo.gov/su_docs/fdlp/pubs/explain.html

Berring, Robert C. and Elizabeth A. Edinger. Finding the Law. 12th Ed. St. Paul, Minn.: Thomson/West, 2005.

Sears, Jean L. and Marilyn K. Moody. Using Government Information Sources: Print and Electronic. 2nd Ed. Pheonix, AZ: Oryx Press, 1994.

Jacoby, Karl. Crimes Against Nature: squatters, poachers, thieves, and the hidden history of American conservation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

“Snail Darter Halts Dam--For Now.” Science News 113 (1978): 403.

Chesapeake Bay Program. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Chesapeake Bay: Introduction to an Ecosystem. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1995. (EP1.2:C42/14/995).

Congressional Serial Set. Hearings Senate Commerce Committee 88th Congress Pesticide Research and Controls. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1964. (Y 4. C 73/2: 88/66)

“Executive Order 11990 – Protection of Wetlands.” Federal Register 42 (24 May 1977) p. 26961.

Index to Publications of the USDA, 1901-1925. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932.

Milwaukee Health Department, School of Health and Sanitary Science. Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, 1918. (WI-M6 HE.4:B8/1915-1918).

United States Code Service Lawyers Edition. 16 USCS Conservation 1531 – 2700. Charlottesville, VA: Lexis Law Publishing, Cha1999.

U.S. Census Office. First Census of the U. S. 1790 (reprint of the 1802 edition). Arno Press. New York. 1976. (C 3.233/10: 790 reprint)

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin 936: The city and suburban vegetable garden. Washington: Government Printing Office: 1918. (A1.9:926-950).

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin 937: The farm garden in the North. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918. (A1.9:926-950).

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture, 1901. “Little known varieties considered worthy of wider dissemination (381-392).” Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902. (A1.10:901).

U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880, Volume 5 Report on Cotton Production Part 1. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1884. (C 3.233/10: 880/5)

U.S. House. Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries. Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Industry Problems hearing, July 22, 25, 31, 1968. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1968.

Wisconsin Commissioner of Health, Milwaukee. Report, 1918. (WI-M6 HE.1:1917-1920).

Page revision date: 23-Mar-2009