Lecture 1:

The Portage: A Small Place in Large Contexts

Suggested Readings:

Juliette Kinzie, Wau-Bun: The Early Day of the North-West (1856)

John Muir, My Boyhood and Youth (1913)

Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (1920)

Zona Gale, "Bridal Pond," The American Mercury (February 1928), 213-16.

William Cronon, "Landscape and Home: Environmental Traditions in Wisconsin," Wisconsin Magazine of History (Winter 1990-91), 83-105. PDF

This lecture models several ways of looking at a landscape: looking with curious eyes, looking in ways that ask unexpected questions—pointing toward unexpected stories—about a seemingly mundane, storyless place. Pay at least as much attention to how this lecture organized its stories and insights as you do to the specific dates, names, or landmarks it narrates...and pay especially strong attention to how the lecture changed the

Introduction: The Fox River in Portage, Wisconsin

Here is an ordinary-seeming place: a roadside picnic area beside a bridge where State Highway 33 crosses the Fox River, with an old farmhouse, fence, and windmill up the hill: a typical and seemingly unremarkable Midwestern landscape.

State Hwy 33 Bridge over the Fox River

And yet, if we look closely we might begin to wonder: Is this such an unremarkable place? What stories—big and small—haunt this physical landscape, and how can we begin to recognize the imprints left by past humans and non-humans?

What physical cues remind us that this place, like every place, has a history?

Wisconsin Historical Society's Fort Winnebago Sign, 1957

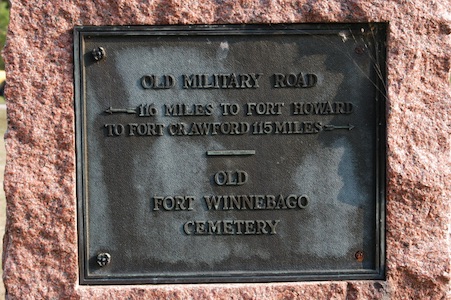

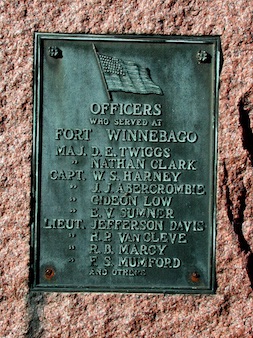

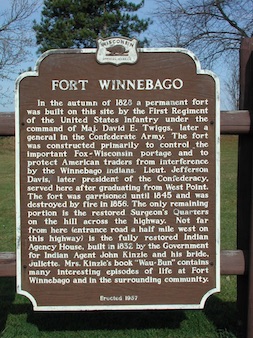

We might look at formal historical monuments: an official marker installed here in 1957 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin commemorates the construction on this site of Fort Winnebago, a frontier outpost built by the US Army in 1828 to help impose the rule of American law on local native populations; near this 1957 marker is an older one from 1924, made of red Wisconsin granite pillar installed by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) to commemorate Fort Winnebago, the Old Military Road, the surrender of an Indian chief named Red Bird, and the names of military officials who served at Fort Winnebago.

If we knew the stories behind these names, they might become more interesting to us. For instance, the name at the top of the plaque, right under an engraved image of the American flag, is that of Major David Emmanuel Twiggs, who led the troops who built the fort in 1828, and whose latter claim to fame (or infamy) would be his role in surrendering the Union troops in Texas to the Confederacy many weeks before the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter at the start of the Civil War. Knowing his story (which of course he himself didn't know lay in his future when he lived at this fort) changes forever the way we think about his name on this plaque. Other names on the plaque have comparably interesting stories, but those memories are now lost to most people who now examine this plaque.

But look again. There is one name toward the bottom of the plaque that is almost certain to provoke a shock of recognition: Lieutenant Jefferson Davis is listed on the DAR plaque. So we ask ourselves: could this be the Jefferson Davis we know from the Civil War, and if so, what was he doing here, so far away from his home in the South? What events transpired between his short-lived tenure at Fort Winnebago and his eventual rise to become a U.S. Senator from Mississippi, Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce...and President of the Confederate States of America?

Learning to Think Like a Historian

To ask and answer these above questions is to do the work of being a historian. History is the drawing of connections that make it possible for long-vanished lives and landscapes to live again in the consciousness of living people now, in the present.

Remember: history is not the past. It is the stories we tell about the past. Unless we tell stories about past people, places, or ideas, they vanish. So doing history involves undertaking an act of resurrection: historians breathe life into inert past places and people via storytelling.

On this quiet section of the Fox River: Jefferson Davis links this place to a story that is national, even global in its significance: a story about the American Civil War. "A story that matters": we pay attention to Davis' name because it resonates with a set of events about which we we already know because of the importance so many people ascribe to them.

But most places are mainly remembered by the people who live there, with no claim to significance and not talked about in history classrooms or textbooks. We call those places "local" and most of the time we feel quite comfortable ignoring all but the ones in which we live or travel through.

So why and how do certain places become significant in our collective histories?

Some places become historically significant because they sit at the center of dense networks of human and economic life (e.g., Rome, London, New York). Some places become historically significant because they were the sites of events (often violent) that come to be viewed as having major historical impact (e.g. Waterloo, Gettysburg, Sarajevo, Dallas' Dealey Plaza). Still others are linked to the life of a famous person (Elvis Presley's Graceland, Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin).

History can alter how we experience landscape. The same is true of memories, but local memories are similar to local places we know: they don't reach very far and not many people care about them. What would it look like to tell histories of places that we don't typically feature in our collective histories? How can we find ghosts of the past in places without formal historical markers?

Stories of the Fox River: A Peopled History

The Fox River is of historical significance in part because of the people who once lived there:

- A mile from Fort Winnebago on the Fox River: childhood home of Frederick Jackson Turner, the University of Wisconsin historian whose 1893 essay "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" remains one of the most influential interpretations of the US past that has ever been written.

- Twelve miles downstream from Fort Winnebago on the Fox River: childhood home of John Muir, celebrated American nature writer, founder of the Sierra Club, and passionate defender of wild places.

- Ten miles west of Fort Winnebago: "The Shack," site of Aldo Leopold's efforts at ecological restoration and the place where he gathered the thoughts he wrote about in his classic work of environmental history and conservation, A Sand County Almanac.

These three men profoundly shaped American ideas of nature in the twentieth century, particularly the meaning of wilderness in American culture. Turner narrated American history as a story of wilderness giving way to civilization; Muir defended wilderness against that same civilization; and Leopold sought to restore wild nature and link it more closely to the lives of urban Americans. The Fox River Valley played a crucial role in shaping the thinking of all three men, which seems at least a little ironic because many today would have trouble seeing much wildness here.

The Fox River is of historical significance because of the writers who once lived near it and told stories about everyday life accessible to wide audiences:

- Old Indian Agency House (1832): home of Juliette Kinzie, author of Wau-Bun - The Early Day of the Norhtwest, which narrates a more humble, "bottom-up" history of life as a white woman living in the expanding American West at the same time that Fort Winnebago was garrisoned.

- Home of Zona Gale, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Miss Lulu Bett. and many other novels, stories, and poems about Wisconsin and the Middle West

Memoirs and fiction give access to intimate details of private lives that often don't appear in more traditional history books, and thus offer perspectives on landscapes and places and human lives that can be invaluable in helping us understanding the meanings of a place for those who live there.

To repeat: History is not the past, but the stories we tell about the past. Fiction can serve to resurrect the past as well as non-fiction, sometimes better than academic history does.

It is not that history is linear and nature cyclical; instead, it is our concern for "what happened? and what happened next?" that pushes us to pay attention to things that happened only once—thus to the linear tales that characterize most history writing. Science and religion are both more likely to concern themselves with cyclical phenonema.

Re-Telling the History of the Fox River: Reading the Landscape

Notice on a topographical map: the very strange bends in both the Fox and the Wisconsin Rivers that bring them into such close proximity even though they then flow toward opposite sides of the continent. Why do these rivers flow as they do, in a very flat landscape? And how does the topography of the area contribute to the area's historical significance?

Portage, Wisconsin: the site of one of the shortest and yet most important portages between two major watersheds on the North American continent, 1.25 miles, 2800 paces.

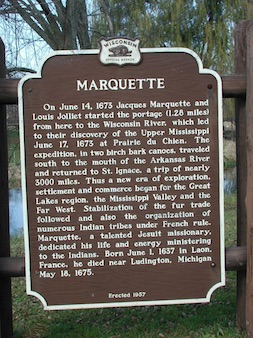

Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were the first Europeans to cross this portage in 1673, following a route that had been known and used by native travelers for millennia. The historical marker of the Wisconsin Historical Society that commemorates these events conveys this most famous of all stories about this place in a single sentence: "On June 14, 1673, Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet started the portage (1.28 miles) from here to the Wisconsin River, which led to their discovery of the Upper Mississippi June 17, 1673, at Prairie du Chien." The Portage became a linch pin in connecting the two French colonies of Quebec and Louisiana, making water travel possible between Montreal and New Orleans.

What is a portage? "To portage" (for the French verb porter, "to carry") is to carry a canoe or other boat overland from one river to another; "a portage" is the place where one does the carrying. In the days before highways, rivers were the chief means of moving people and goods over long distances. Portages marked the boundaries not just between watersheds but different political territories. With the arrival of Europeans and their imperial systems in North America, portages also often became sites for treaty negotiations.

Portage, Wisconsin: here, to walk the 1.25 miles between the Fox and the Wisconsin Rivers is to reenact a crossing between two massive watersheds: the crucial transportation corridor that was the Wisconsin River draining into the Mississippi River draining into New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico; and the Fox River draining into Lake Michigan, the St. Lawrence River, and the North Atlantic. Because so much of the eastern United States is drained by just two great rivers — the Mississippi and the St. Lawrence -- the line between their watersheds, when joined with a few others on the eastern seaboard like that of the Hudson, has many more than its fair share of historically significant portages.

The portages became objects of political contestation. Treaties (often negotiated at portages) were signed to control them; forts were built to defend them; and various economic activities and services grew up along their routes. Towns emerged at these sites, and transportation corridors concentrated there even as water travel gave way to roads and railroads. This was in fact the story that Frederick Jackson Turner told about his home town, mapping it outward to become what he saw as the master narrative of American history. The buildings and structures of the town of Portage that grew up near this route eventually erased almost all traces of the old portage , but beneath the modern road that now follows that route is a foot path more than ten thousand years old.

Reading the Landscape

There is no richer or more rewarding a historical document than a landscape. How do you read a landscape to evoke the many stories whose traces can be glimpsed upon and beneath its surface if only you know where to look? This class will teach you map-reading, historical research, and skills for looking closely. It will teach you to read landscapes and see the stories they have to tell.

State Hwy 33 Bridge over the Fox River

An afterthought not mentioned during the lecture: this quotation from the novelist Wallace Stegner may help you remember one argument central to this introductory lecture:

"No place is a place until things that have happened in it are remembered in history, ballads, yarns, legends, or monuments. Fictions serve as well as facts."

Wallace Stegner, "The Sense of Place" in *Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs (New York: Random House, 1992), 199-206.*

Please re-read the italicized paragraph at the top of this notesheet and reflect not just on the information you learned from this lecture, but the different ways the lecture went about constructing and weaving together its several stories.