Lecture #7:

A Path Out of Town from Madison: Driving West from Madison's Capitol Square

Reminders:

We'll be talking about Christopher Wells's Car Country (2013) in section next week, and that book will surely appear on the midterm exam. Your first paper assignment is due next week, and it too is based on Car Country. The book is by far our most important reading for today's lecture topic. It is, by the way, available as chapter-by-chapter downloads via the UW-Madison Libraries portal.

I. Introduction

In this lecture, we'll take a drive from the center of downtown Madison out into western Dane County. One way to think about today's lecture is as a landscape history of the United States as Car Country, as expressed at the local level in our home town. Another way to think about today's lecture is as a historical geography of American transportation networks in the twentieth century, particularly of automobile transport as a defining feature of the landscape we experience today.

In the United States and Europe, cultural landscapes are symbolically perceived in four broad categories: Wild / Pastoral (or Working Lands) / Suburb / City. Today, in thinking about automobile transportation, and all the landscape elements that go into supporting it, we'll be asking: How are these four cultural landscapes interconnected with each other?

Key points to observe about these four cultural landscape categories:

- These are human landscape categories, not natural ones

- Each exists only relative to (and in scale with) the others

- They are arrayed along a continuum...

- ...but derive their meanings from counterpoints with each other

- Each embodies complex cultural values

- All shaped by economics, policy, design, transport, other forces

- All express long histories that are both material and cultural

Let's notice an especially interesting assumption that we often don't consciously recognize about cultural landscape called "wilderness." Roadlessness has been a key part of the legal definition of wilderness since it was written into federal law as part of the 1964 Wilderness Act. So at one end of the spectrum of American cultural landscapes, wilderness is perceived as lying at the far pole from the city, the wild, roadless place where we leave Car Country behind. And yet there's also a paradox here: we rely on roads and cars to reach the roadless landscapes of the wilderness, so political and cultural support for protecting wilderness depends at least in part on automobile access..

Today's lecture is not just a journey through space; it is also crucially a journey through time. So one way to think about a landscape is as layers representing different moments in time.

One of my favorite metaphors for this is to think of a landscape as a palimpsest: a word that refers to a medieval manuscript written on vellum in which a scribe has scraped off the ink of an earlier text in order to reuse the page to record a new text on top of the old one, yet the older text can still be glimpsed beneath the new one. Repeatedly in this course, we'll view landscapes as palimpsests.

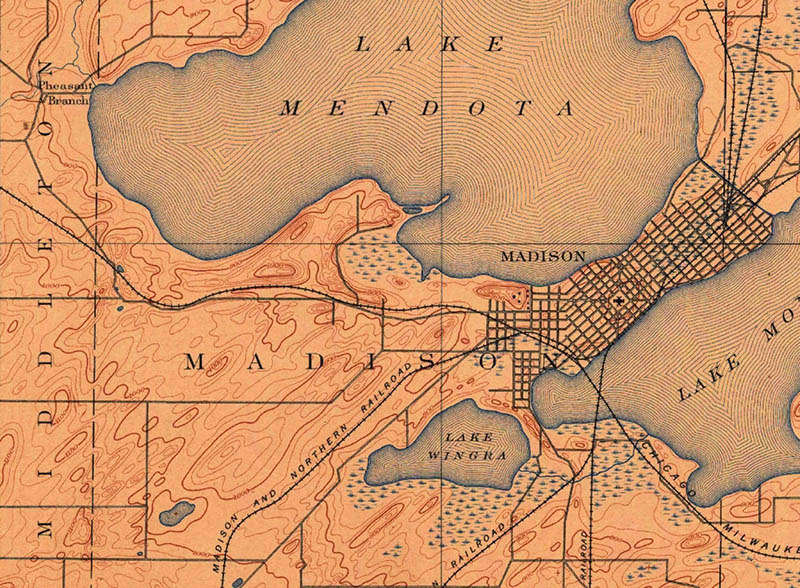

The lecture began by viewing the United States Geological Survey's (USGS) 1890 topographic quadrangle map of the Madison Isthmus and the rural countryside west of the city's settled area, a link to which you'll find below. The key thing to notice about this map is that everything in it predates the automobile. As such, the map is a record of what Madison looked like before it began to be absorbed into and transformed by Car Country.

The transportation networks on display here are twofold: 1) the grid of city streets on the Isthmus, which were designed for a world of horses and carriages and eventually trolleys; and 2) the railroad network as it existed as of 1890, largely built during the second half of the nineteenth century.

USGS, Madison West Topographic Quadrangle Map, 1890

USGS, Madison West Topographic Quadrangle Map, 1890

Here's a question I urge you to keep track of throughout this course, taken from the title of a 1973 book by the regional planner Kevin Lynch: What Time Is This Place? You will almost always gain valuable new insights into landscapes and their histories when you ponder this question.

To illustrate how you would think through this question, I spent quite a while at the start of lecture pondering two sets of documents.

The first consists of aerial photographs of the southwest side Madison near the curve of the Beltline Highway as it wraps around the area we now think of as West Towne Mall. I first showed a series of aerial photographs from 1949 to the present, all the while asking "what time is this place?" An obvious narrative embedded in these photographs is the gradual conversion of the agricultural countryside from "rural to urban."

So you can explore this these aerial photographs to ponder this process of conversion for yourself, here's a PDF of that part of the lecture's PowerPoint (warning: it's quite a large 15mb file, so be sure you're on WiFi when you download it!) : PDFThe second set of documents constitute the rest of the lecture: aerial and streetview photographs along a route from West Washington Avenue to Regent Street to the Speedway to Mineral Point Road, starting at the State Capitol and proceeding west out of town as far as State Highway 78 west of Pine Bluff.

The route we'll follow can be thought of as a "transect line," modeled on an ecological technique developed for sampling vegetation in a given study area by following a line across the site and counting all the organisms and species encountered along the route. In our transect, we'll encounter an array of cultural landscapes from city to suburb to rural countryside (including what pass for "wild" areas in western Dane County). But since the city has been expanded outward from its original historic center when it was first laid out in the 1830s, we'll also move outward through more and more recent periods of history (recognizing that older parts of the landscape, which have been transformed and overlaid by more recent historical changes and processes, often remain visible, as with a palimpsest).

To be explicit about the periods I'll use to build a narrative as we move west along this transect, here are the chapters in the story I'll be telling:

- the Wisconsin State Capitol (completed in 1917 after previous building burned down in 1904; it is the fourth such building at this location, sitting in the square that has been at the center of the street grid of Madison's Isthmus since those streets were first laid out by James Duane Doty in 1836.)

- Surrounding suburbs ("1880s streetcar suburbs") along West Washington St. west of Broom St.

- Regent St. between West Washington and Camp Randall Stadium, exemplifying "highway retail strip" styles from the 1920s-1960s.

- University Heights, laid out in 1891 and largely constructed between 1891-1930.

- Forest Hill Cemetery, a romantic landscape first laid out in 1857-58.

- Mineral Point Road between the cemetery and Midvale Boulevard, largely constructed between 1940-1960.

- Mineral Point Road from Midvale Voulevard west to the Beltline, automobile suburbs expanding westward during the decades following World War II.

- Countryside west of Beltline, where rural farming landscapes are being transformed by exurban development as people search for "a room with a view."

II. Tracing a Path Out of Town

Proceeding southwest from the Capitol, we drive past houses on West Washington Avenue west of Broom St constructed during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Strikingly, most are double- and triple-decker houses, and all have porches. It's only if we recall that the structures on this part of West Washington precede the advent of automobiles that we can see that these porches were once centers of family life: children playing in the yard and the on the front sidewalk, something that was safer for them to do (under the watchful eyes of parents and neighbors) in an era before heavy cars moving at dangerous speeds barrelled down West Washington Avenue.

No less strikingly, because this neighborhood was built before the coming of automobiles, no provision whatsoever was made for parking here. For the rest of our journey west, we'll be looking to see how neighborhoods from different eras were constructed relative to the need to accommodate car ownership and transportation. Here, notice that driveways are punched out in the narrow gaps between houses, and back yards have almost universally been converted into parking lots--many charging substantial rents--because that's the easiest place to find space for cars.

As we move west out of Madison, we'll watch porches disappear. We move onto Regent Street which, for the purposes of today, we'll call a "strip" -- a cultural landscape that emerged during the middle decades of the twentieth century as retail store owners redesigned their layouts and advertising to deal with customers in cars. How do you get people driving past in cars to stop and come into the store? And if they want to do so, where will they be able to park? Notice the billboards designed to attract the attention of drivers, and notice buildings set back from the street with parking in front. Notice how the landscape is beginning to respond to the presence of automobiles...we're entering Car Country now.

In this same area, the Greenbush neighborhood shows its roots as the first home of immigrant Italian stone masons who did the carvings so abundantly on display in the State Capitol and the Wisconsin Historical Society. As its original Italian and Jewish ethnic working-class residents moved out of this neighborhood after World War II -- and as people of color began to replace them -- the neighborhood came increasingly to be regarded by political leaders as "blighted" and became the object of efforts at "urban renewal" which removed the original housing stock and its residents. In Greenbush, institutional medical buildings from the 1960s hollowed out what had once been a vibrant working-class ethnic neighborhood.

We move past Camp Randall and into the University Heights neighborhood, where houses were constructed mainly from the 1890s-1920s. Here we again observe the problem we saw on West Washington: how to create parking space for residential areas built before cars. In the University Heights, parking originally began to appear as sheds in back yards, with driveways (often shared) inserted in the narrow space between adjacent houses to reach those sheds. Later, garages (almost always with space for just one car) were inserted when space permitted by adding lean-to's or other additions to existing houses. Only later in the history of the neighborhood do you a few houses begin to show garages that were designed at the same time as houses were built.

We next go down the Speedway, which got its name because the speed limit here increases from the downtown normal of 25mph to 30mph--which felt very speedy when the road first got this place name! Forest Hill Cemetery on the south side of the Speedway dates from 1857-58, and is a wonderful example of a nineteenth-century romantic cemetery patterned on Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The concept of such romantic cemeteries was to visit graves and contemplate one's own mortality with a journey out of the city and "into nature" in the surrounding rural countryside. Forest Hill was at least a mile out in the country when it was built. (If you're interested, you can learn more about its history from this excellent website: http://foresthill.williamcronon.net, developed by a group of graduate students here at UW-Madison.)

As we move farther west past the Speedway along the northern edge of the Westmorland neighborhood, houses date from the era after World War II. One way we can know this is that garages are now built into the house facade, though initially only for a single car. Notice, too, that porches have begun to disappear. In automobile suburbs, more and more family life was happening in back yards rather than front yards. Backyard "decks" eventually replaced front-yard porches for many such families. We also see institutions like churches moving away from the downtown along with their parishioners. Our Lady Queen of Peace on Mineral Point Road, for example, orients itself so that its backside faces the busy street; its front faces south, away from Mineral Point Road, towards the large parking lot where its parishioners can park their cars.

The farther west we go, the more the facades of houses are consumed by their garages, as we see the emergence after the 1960s of two- and even three- or four-car garages. As we approach West Towne Mall (opened in 1970, followed by East Towne Mall in 1971), notice the prevalence of free parking—contrasted with the lack of such free space downtown—which in the era of the automobile suburb was an essential attraction of this new retail landscape. Downtown merchants had increasing trouble competing with large single-story malls like this one partly because of the parking problem, and partly because growing numbers of customers drove to these malls and big-box stores from greater and greater distances, enabling retailers to purchase products in larger volumes at lower wholesale prices. Smaller downtown stores had trouble competing in this new car-driven economic environment, and many went out of business as a result. Much of the geography of post-World War II suburbia depends on these underlying economic relationships.

Continue west, go under the Beltline, and all of a sudden—because of zoning laws—we enter a landscape that is abruptly (and temporarily) rural.

Further west, we see Black Hawk Church in the landscape, again made possible by cars bringing in worshippers from a wide geographic area. We are still solidly in Car Country.

When looking at rural America on the urban fringe, we might wonder at this question: why do well-to-do Americans so often seek to live close to nature, to have a "room with a view?" This landscape is on the edge of the Driftless area, and from here we can see the line of urban development marching towards these fringe spaces. Once again, the car can help explain development here: working lands with working farms created the need for good roads to move dairy products, which now also create the conditions for residential development (to say nothing of famously good bicycle riding). But these areas retain their views only if grazing animals, farming, mowing, and/or prairie restoration prevent trees from growing up to become forests that block the pastoral views -- and only until suburban housing developments don't grow up to block the views of the first exurban migrants.

Although the examples we've explored in this lecture are particular to Madison and Dane County, they in fact reflect patterns of land use that are widely dispersed throughout the landscapes of the United States. Learning to recognize the history of Car Country, as Christopher Wells's book will teach you to do, will give you powerful new tools for reading the landscape of twentieth-century America and telling its many complicated stories.