History / Geography / Environmental Studies 469

The Making of the American Landscape

This course surveys the history of the United States and its colonial precursors from an unusual perspective: the evolution of the American landscape. Designed to complement existing courses on American environmental history and the history of the American West, it begins by orienting students to the geography of the North American continent, paying special attention to those features--geology, physiography, climate, vegetation, ecology--that have had the greatest influence on human lives in different regions. It also offers tools for interpreting landscape: different ways of periodizing the American past, different ways of mapping American space, different ways of narrating American historical geographical change. Once this basic introduction has been completed, the course explores different elements of the national landscape at moments when they became prominent features of American life, tracing their stories forward in time. Eclectic rather than encyclopedic, it focuses on landscape elements and processes most likely to be helpful to students as they try to understand the world around them.

For many years, my survey course on American Environmental History (History / Geography / Environmental Studies 460) asked students to write a "place paper" in which they select a place they know well and write an environmental history of that place. Although this proved to be a wonderful assignment, and many students report having benefitted a great deal from it, I was never completely confident that a lecture course focusing mainly on systemic environmental change, ideas of nature, and environmental politics really gave students the tools they needed to write these place papers. This new course on "The Making of the American Landscape" is my solution to this pedagogical problem: by tracing the physical, cultural, economic, and material evolution of the nation's different landscapes, it seeks to lay much firmer foundations on which student place papers can be constructed. With this in mind, I moved this semester-long final research assignment from 460 to 469, which means that the various resources I developed for the place paper are now available for this course.

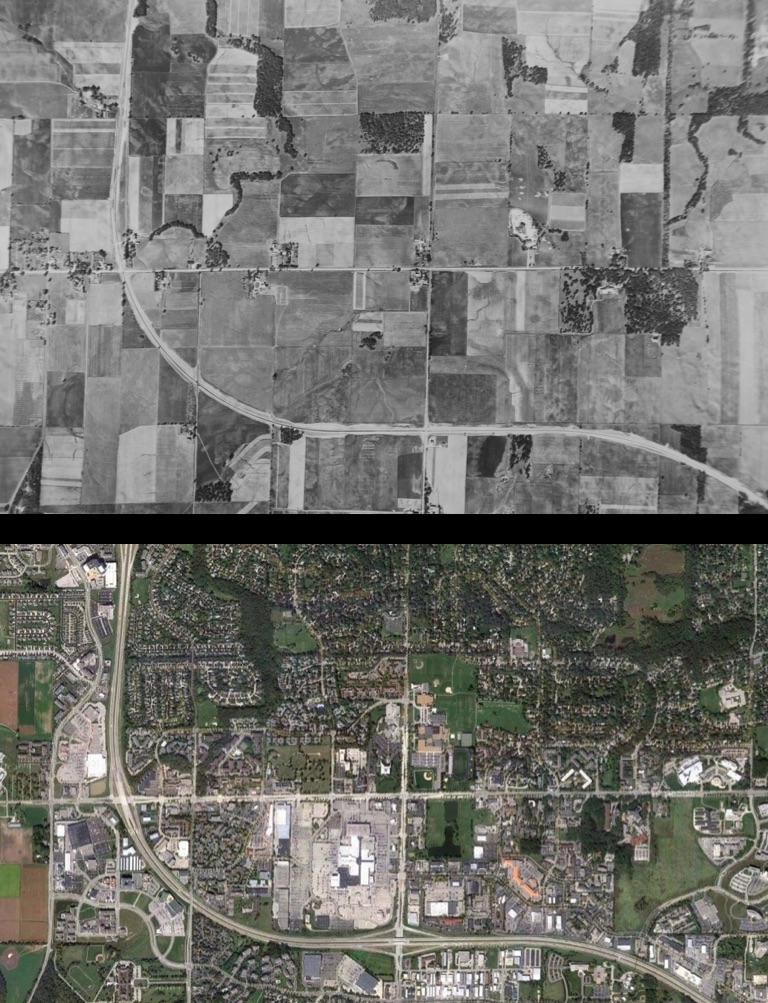

Although 469 is every bit as much a survey of environmental history as 460 is--and the two courses are designed to complement each other with as little repetition as possible--469 focuses much more on the evolution of the material landscape and the various historical relationships that have shaped it over the long sweep of American history. As such, 469 places more emphasis on historical geography than 460 does, and it also spends more time teaching students concrete skills for reading the landscape: interpreting maps and aerial photos; using natural features to understand settlement patterns; tracing the growth of transportation networks; the evolving infrastructures of water supply, sewage, energy, and other such systems; the history of architectural construction and the built environment; and so on and on. By the time students complete this course, they should have in their personal toolkits a set of skills for interpreting landscapes that they can use for the rest of their lives. As such, the course is an intentional homage to Aldo Leopold's famous Wildlife Ecology 118 course at the University of Wisconsin, first taught in 1939, in which "reading the landscape" was one of his chief goals.

"The Making of the American Landscape" aspires to give students not just a survey of the changing landscapes of the United States from colonial times to the present, but also different ways of seeing those landscapes, so that our national history and geography come alive in new ways. By the end of the course, students will have learned to:

Identify numerous features of the American landscapes and understand their origin and evolution;

Think spatially and geographically about historical change;

Improve their skills in reading maps, satellite photographs, and other cartographic documents;

Do digital and archival research to trace the history of a particular American landscape;

Learn to juxtapose sources and research questions to yield original historical interpretations;

Apply alternative periodizations to changing landscapes in order to narrate their pasts;

Synthesize historical geography at the national scale to interpret local landscape change;

Learn to view landscape as the extraordinarily rich historical document in which they themselves live.

Syllabus

HTML (optimized for viewing on screen, with active links)

PDF (optimized for printing)

Email Announcements Sent to Class List Server HTML

Handouts:

Whenever possible, I'll try to make note sheets available for each lecture by sometime on the morning of the lecture; if that proves impossible, I'll post them within a few days afterwards.

Copyright restrictions prevent me from providing copies of most of the maps, photographs, and other illustrations that appear in lectures. When possible, we've provided a few links in the notes to websites where you can access additional content of this kind, but you can also do so yourself by performing a Google Image search for the materials you're seeking, and also perusing the relevant entries in Wikipedia, many of which contain very helpful (and copyright-free) maps and images. Finally, remember that you can access online a classic collection of historical maps for many of the topics discussed in this course in Charles O. Paullin's 1932 Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States.

Handout #1: The Portage: A Small Place in Large Contexts HTML

Handout #2: What Is Landscape and Why Should We Care About It? HTML

Handout #3: Landscapes of Information: An Introduction to Your Place Paper...and to UW-Madison Libraries HTML

Handout #4: An Introduction to North America HTML

Handout #5: Online Cartography: Tools for Landscape Reading, Past and Present HTML

Handout #6: Mapping the Continent: A Tour of Cartographic History HTML

Handout #7: A Path Out of Town from Madison: Driving West from Madison's Capitol Square HTML

Handout #8: Rivers and Harbors, Roads and Rails, Highways and Airports: Movement Transformed HTML

Handout #9: Periodizing Landscape Change: Which (and Whose) Narratives to Choose? HTML

Handout #10: Telling Tales on Canvas: Mythic Narratives of Frontier Change HTML

Handout #11: Names on the Land: Place Names as Historical Evidence HTML

Handout #12: The Many Worlds of Indian Country HTML

Handout #13: Course of Empires: Spain, France, Britain, and the United States HTML

Handout #14: Bounding Property: Survey and Sale HTML

Handout #15: Farms and Markets HTML

Handout #16: Slave and Free HTML

Handout #17: Landscapes Made Red: Military Geographies HTML

Handout #18: Forests: The Westward March of Logging HTML

Handout #19: Underground Landscapes of Wealth and Work HTML

Handout #20: On Serendipity: The Great Diamond Hoax HTML

Handout #21: Weaving an Often Forgotten Web: Systems, Networks, Infrastructures HTML

Handout #22: Built Environments of Domesticity and Commerce HTML

Handout #23: Color Lines, Part 1: Fractal Landscapes of Race and Ethnicity HTML

Handout #24: Color Lines, Part 2: Landscape Legacies of Jim Crow HTML

Handout #25: Zoned America HTML

Handout #26: Practicing Landscape History HTML

Map Library Exercise

Please be sure to complete this exercise in time for your discussion section during the week of September 24. If you can visit the Map Library and do this assignment together with one or more students from the course, it should be both more enjoyable and a richer learning experience. Also, please note that the web page with the exercise includes a link to an inventory of all the maps we have on display in case you'd like to have a full list while you're at the Map Library. HTML

Supplemental Materials for Reading Christopher Wells' Car Country

Christopher Wells' website and video about Car Country

Kate Wersan's Tips for Reading Christopher Wells's Car Country PDF

Cronon Foreword, "Far More Than Just a Machine," for Christopher Wells's Car Country PDF

Place Paper Assignment

Full details of the final place paper assignment are included in the course syllabus, but we also encourage you to spend time reading excellent examples of these papers from the work of past students in 460 and 469. You'll find a large collection of them catalogued on this page.

An Historical Atlas of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Campus

We've assembled a sequence of historic aerial photographs that will enable you to explore the growth and changing landscapes of the UW-Madison campus from 1937 (the year the first such aerials began systematically to be taken) until the present. This should be helpful to you as you think of the campus itself as a series of landscapes to which you can apply some of the insights of this course; you may even decide you'd like your place paper to focus on some aspect of the UW-Madison campus. Please be sure to visit and explore the links on this page: HTML

Midterm Exam with Exemplary Blue Book Essays

A good blue book essay answers the question it addresses in a well-structured way with abundant illustrative details drawn from lectures, readings, and your own reflections on the landscapes we're studying in the course. The most common problem on this fall's midterm exam was students not providing enough of the textured, fine-grained details that are essential to understanding the historical geography and environmental history of a time, place, and landscape. To help you see what an excellent blue book essay should look like, we've asked three students who earned high marks on the midterm exam to share their essays (anonymously) with the rest of the class, which they've generously agreed to do. You'll find them linked below.

Midterm Exam PDF

Sample Exam #1 PDF

Sample Exam #2 PDF

Sample Final Exam

Here's an example of what the final exam for this course will look like. It consists of the practice objective matching section that I shared with the class at our review session on December 10, along with the four essay questions that students in 469 were offered on their actual final exam in December 2016. In reviewing for the exam, we strongly encourage you to go back and review the exemplary blue book essays from the midterm exam that we provided in the links immediately above. Good luck with studying!

Sample Final Exam PDF